The good books are the fruit of the tree of knowledge all right, and the devil is always offering us another fellow's damned opinion, which, were we to sample it, might cause the scales to fall from our eyes, so to see sudddenly that king and queen, God and all the angels, are naked, shivering, and in sore need of shoes. That is why just one good book, however greatly good, when used to bludgeon every other, turns evil; why we should be onmivorous: try kale, try squid, try rodent on a spit, try water even though there's wine, try fasting even, try--good heavens!--rice with beans. The good books are cookbooks and good readers read them, try them, stain their pages, adjust ingredients, pencil in evaluations, warn and recommend their recipes to friends.

~~

Yet, what is the goodness that makes the good books good? That confers this greatness on the great ones? Whence comes the character of "the classic" that gives it that cachet?

They glow because their authors are such fine, upstanding people from the best families, graduates of the most expensive schools, and representative of the nobler classes. When I was your age, we would have said to that suggest: in a pig's ear. Do you see a halo hanging over Heidegger's head? Their authors are murderers, thieves, traitors, mountebanks, misogynists, harlots, womanizers, idlers, recluses, sots, sadists, liars, snobs, lowlifes resentful of any success, vicious gossips, gamblers, addicts, ass-lickers, parvenues, whose pretenses to nobility were (and are) notorious: for instance, the clown whose father was a highland peasant named Balssa, lately come to town, and who renamed himself Balzac after an ancient noble family, and finally put a "de" before it, as if he were parking a Rolls in front of a tenement in the belief it might cause the johns to flush--a house, when Henry James paid a visit to Tours to take in the birthplace, he found to have been recently built but already a ruin, a row house that could at least have had the dignity, he said, to be "detached"--yes, a cheap pretender, this Balzac, who would go on to create a world more orderly than God's, almost as complete, and from beginning to end in better words, commencing with the fact that they were French. How about alleging that they glow because the good books uphold the finest ethical examples, support the highest values, display the most desirable attitudes? The way

The Inferno is a testimonial to forgiveness? Or the

Iliad a paean to pacifism? And by such edifying examples of revenge or the pleasure of killing an enemy, morally improving their readers, agenbiting their inwits, bestirring them to love their neighbors a bit better than themselves. Well, up a donkey's rear to that, too. One of the many lessons ours great teachers, the Nazis, taught us is that no occupation, no level of society, of wealth or education, no profession, no religious belief, no amount of talent, intelligence, or aesthetic refinement can protect you from fascism's virus, not to mention a dozen others. It is not a contradiction for the Chaucer scholar to beat his wife, especially if she resembles the Wife of Bath.

~~

The healthy mind goes everywhere, one day visiting Saint Francis, another accepting tea from Celine's bitter pot--ask for two sugars, please--and hiking many a hard mile through Immanuel Kant or the poetry of Paul Celan--a pair who will provide a better workout than the local gym--before taking a hard-earned vacation in the warm and luscious fictions of Colette. You will live longer and better by consuming deliciously chewy fats and reading Proust than by treadmilling to a Walkman tune and claiming to be educated because you peruse the

Wall Street Journal and have recently skimmed something by Tom Wolfe.

--William H. Gass,

A Temple of Texts

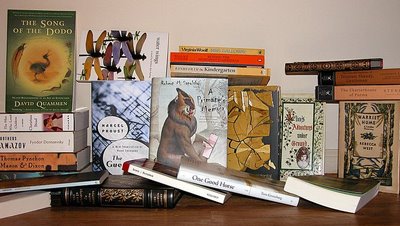

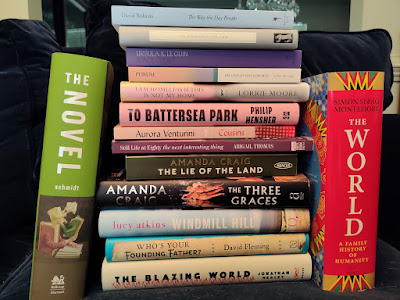

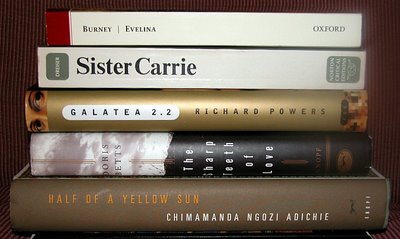

Okay, so I decided only one short month ago that I wouldn't stockpile books. And granted, the stack above has all the markings of yet another stockpile.

Okay, so I decided only one short month ago that I wouldn't stockpile books. And granted, the stack above has all the markings of yet another stockpile. Claudius and Nicholson consider the top of the sofa in the study their favorite hangout. Easy access to the window, plenty of room for joint naps, and they can keep tabs on who's using the computer across the room.

Claudius and Nicholson consider the top of the sofa in the study their favorite hangout. Easy access to the window, plenty of room for joint naps, and they can keep tabs on who's using the computer across the room.