Saturday, December 31, 2011

2011 reading stats and favorites

So what conclusions have I drawn from this year's hastily-assembled reading stats?

That while 82 completed books (I've lost count of the number of books set aside, yet still in progress) is quite respectable, if not awe-inspiring, I'm still a little bummed when I compare that number to the 101 that I managed the previous two years. Couldn't I have looked at less kitchen porn, read fewer political blogs? Couldn't I have tried harder to convince the guys that six seasons of Lost should take longer than five weeks to watch? Perhaps I could have finished a bit more nonfiction, read a volume or two of poetry, if I'd used my time more wisely.

But of course the most appalling stat is the number of new books that came into the house and remained unread. Dare I mention that I ordered three more this morning, before I go cold turkey for the next three months? Only one of those books do I intend to read right away; I should have waited on the others.

My reading stats for the last seven years (this year's in bold):

Books Total 82 / 101 / 101 / 78 / 81 / 74 / 77

Nonfiction 12 / 16 / 15 / 13 / 8 / 14 / 13

Novels 66 / 78 / 79 / 62 / 62 / 50 / 47

Short Story Collections 2 / 7 / 7 / 3 / 4 / 1 / 8

Library Books 39 / 26 / 48 / 27 / 14 / 31

Newly Acquired/Read 12 / 23 / 32 /32 / 31 / 24

Newly Acquired/Stockpiled 120+ / 113 / 140 / 88 /141+ / 75+

E-texts Read 12 / 17 / 10 / 12

Free E-texts Read 6 / 9 / 5 / 7

Just-published books 21 / 36 / 55 / 41 /34 / 33

Classics 23 / 21 / 10 / 8 / 23 / 12

Pre-20th Century 10 / 9 / 7 / 4 / 12 / 11

Written by women 38 / 46 / 55 / 42 / 33 / 28

Two plays: Othello and Agamemnon

Authors with multiple books read: W. Somerset Maugham (Wendy and I read five Maughams over the summer); Alice Thomas Ellis (3); H.G. Wells (3); Stewart O'Nan (2); Mary Doria Russell (2); William Styron (2); Anthony Trollope (2); Rebecca West (2); and Connie Willis (2).

Rereads: Othello, Pride and Prejudice, The Razor's Edge, House of Mirth, Darkness Visible and Atonement.

I read several books this year that I finished knowing that I want to read them again some day. At the top of that list is Shirley Hazzard's The Transit of Venus, which the Slaves read back in April.

Other favorites from the year are:

Started Early, Took My Dog. Kate Atkinson

Who Was Changed, and Who Was Dead. Barbara Comyns

Galore. Michael Crummey

The Sisters Brothers. Patrick deWitt

A Visit from the Goon Squad. Jennifer Egan

Wounded. Percival Everett

We Had It So Good. Linda Grant

The Sundial. Shirley Jackson

Skippy Dies. Paul Murray

Doc. Mary Doria Russell

There But For The. Ali Smith

He Knew He Was Right. Anthony Trollope

Among Others. Jo Walton

The complete list of books read in 2011 can be found here.

See you next year!

Wednesday, December 07, 2011

Reading Shakespeare

--DG Strong, "How Shakespeare got me through unemployment"

Monday, November 07, 2011

Something beautiful

--Ali Smith, There but for the

Monday, October 31, 2011

What I read in October

The Revisionists. Thomas Mullen [on the Kindle]

It seems I am surrounded by text in this city. Even without my seeking it out, it haunts me, hovers in the background, is invisibly sent from one handheld to another. I am a mere punctuation mark--we all are--in stories someone else is writing. Or has already written.

Caleb Williams. William Godwin (for the Classics Circuit) [on the Kindle]

The pride of philosophy has taught us to treat man as an individual. He is no such thing. He holds necessarily, indispensably, to his species. He is like those twin-births, that have two heads indeed, and four hands; but if you attempt to detach them from each other, they are inevitably subjected to miserable and lingering destruction.

Nightwoods. Charles Frazier

At some point, Stubblefield wondered how much he was really learning about Luce. She would talk freely about dress patterns, the daily details of gardening, his grandfather. But Stubblefield kept feeling like he was watching a cardsharp shuffle the deck, all the fine subtle movements to misdirect your attention, and at the end, a reassuring spread of hands to hide the pit opening under her life.

Major Pettigrew's Last Stand. Helen Simonson (for book club) [on the Kindle]

"I did give [Kipling] up for many decades," she said. "He seemed such a part of those who refuse to reconsider what the Empire meant. But as I get older, I find myself insisting on my right to be philosophically sloppy. It's so hard to maintain that rigor of youth, isn't it?"

Pillars of Gold. Alice Thomas Ellis

Only a few years before, Camille had been acutely concerned about her mother's appearance, sometimes refusing to be seen with her in public, but now it seemed that she no longer minded: she had expropriated from Scarlet's wardrobe those few articles that she felt would suit herself and had thereafter left her mother to her own devices. It gave Scarlet the impression that she had grown very old and from now on might just as well go round in her shroud.

Home Life. Alice Thomas Ellis

One of the things I like about the country is that the problems it presents are different. For instance while the drain in London sometimes get blocked up it is never because there is a hedgehog in it.Zone One. Colson Whitehead

If the beings they destroyed were their own creations, and not the degraded remnants of the people described on the things' driver's licenses, so be it. We never see other people anyway, only the monsters we make of them.

Saturday, October 29, 2011

The Island of Dr. Moreau: It was the wantonness that stirred me

I've repeated a review only a time or two in the seven years I've been blogging. But I'm dusting off this one from August 2006 (it was a Slaves of Golconda group read) because 1.) I've been reading H.G. Wells this fall; and 2.) I wanted to participate in the Dueling Monsters challenge.

Also, I don't normally respond as viscerally to a book as I did to The Island of Dr. Moreau. As far as I'm concerned, The Time Machine and Invisible Man can't hold a candle to it, and as far as Dr. Moreau himself goes, he's the biggest monster of them all.

~~~~~~~

When I was pregnant with my son I developed preeclampsia. The doctors determined that they'd have to take him out two months early if either of us were to make it.

He spent his first month in a neonatal intensive care unit across town before being transferred to the hospital closest to us until he'd gained enough weight to leave hospitals altogether. A NICU is, of course, a miraculous place of care and compassion, but it is also a place where much pain is experienced.

S. fought against a respirator that insisted on forcing breath in and out at a rate to which his body didn't want to conform; with his face contorting in silent screams, he was continually pricked and poked for blood samples, then transfused with fresh blood when he couldn't make enough to keep up with the amount taken (the scars on his wrists and ankles from the blood-taking did not fade away for more than a decade afterwards). Repeat.

Wired, tubed, and for several days blindered, he suffered. The painful procedures continued until eventually we--doctors, nurses, parents-- could tell that he was not only going to survive, but thrive.

Not all the babies did. There were those of two or three years of age, still in no shape to live outside NICU, abandoned by their parents, depending upon volunteers and scraps of time from the nursing staff for a bit of human contact. And there were several who lasted mere hours or days before they died.

A nurse caught me finger-stroking S.'s tiny arm on one of my first trips to the NICU. Did I not realize how much pain I was causing him? she snapped. Because he had no fat stores, the lightest touch was an assault to the nerve endings just underneath his skin. She taught me to cup my hand around him and to keep it still.

A couple weeks later I saw a new mother stroking her baby the way that I had. I waited for a nurse to correct her, but no one said a word. I knew then that her baby was going to die. No one was going to deny her the bit of comfort she could gain from touching him, even if her touch caused him distress, because these moments with the baby were going to be all that she had.

As you've maybe gathered by such an introduction, I responded to The Island of Dr. Moreau on a very personal level. If a person, if an animal, is to suffer by someone's hands in a House of Pain, it had better be for a damned good reason.

Moreau, well regarded in scientific circles in London prior to the publication of a pamphlet that exposed his cruel methods of vivisection, left England for a private island in the Pacific where he could continue his experiments outside the strictures of society. By cutting and mutilating and grafting he molds an assortment of animals into a tribe of Beast People, teaching them rudimentary language and a form of religious law designed to keep them under his control even after he has turned them out for retaining undesired animal characteristics. Imperfection really bums the man out.

Each time I dip a living creature into the bath of burning pain, I say: this time I will burn out all the animal, this time I will make a rational creature of my own.

Moreau isn't driven to mold animals into human shapes out a desire to help either man or creature, but merely because he wants "to find out the extreme limit of plasticity in a living shape." Ethics are not of interest to him: "The study of Nature makes a man at last as remorseless as Nature," he claims. Pain is immaterial; it is animalistic; intellectual desire transforms others into problems to be solved, nothing more or less.

Doctor Moreau is, in short, as psychopathic as they come despite the god-like appearance and demeanor that Wells has given him.

Edward Prendick, our narrator, is no match for him. Because Prendick, a shipwrecked gentleman taking shelter on Moreau's private island, has dabbled in natural history and studied biology under the famed T.H. Huxley, Moreau eventually reveals the truth about his experiments to someone he assumes can appreciate them and will henceforth stop hindering his work due to silly behavior. Instead Prendick is horrified, but offers weak and minimal objection. He reminds me of a journalist who lands an exclusive interview and then is afraid to ask any follow-up questions to the canned nonsense he's given. Time and again I wished the narrator were someone like Patrick O'Brian's Stephen Maturin, someone who both understood the science and was willing to argue the ethics of a situation, to insist that being human means behaving humanely toward those not on your level. Someone who could at least read the Greek and Latin classics shelved near his hammock instead of revealing yet another skill he's lacking.

Poor brutes! I began to see the viler aspect of Moreau's cruelty. I had not thought before of the pain and trouble that came to these poor victims after they had passed from Moreau's hands. I had shivered only at the days of actual torment in the hands. But now that seemed to be the lesser part. Before they had been beasts, their instincts fitly adapted to their surroundings, and happy as living things may be. Now they stumbled in the shackles of humanity, lived in a fear that never died, fretted by a law they could not understand; their mock-human existence began in an agony, was one long internal struggle, one long dread of Moreau--and for what? It was the wantonness that stirred me.

Had Moreau had any intelligible object I could have sympathized at least a little with him. I am not so squeamish about pain as that. I could have forgiven him a little even had his motive been hate. But he was so irresponsible, so utterly careless. His curiosity, his mad, aimless investigations, drove him on, and the things were thrown out to live a year or so, to struggle and blunder and suffer; at last to die painfully. They were wretched in themselves, the old animal hate moved them to trouble one another, the Law held them back from a brief hot struggle and a decisive end to their natural animosities.

In these days my fear of the Beast People went the way of my personal fear of Moreau. I fell indeed into the morbid state, deep and enduring, alien to fear, which has left permanent scars upon my mind. I must confess I lost faith in the sanity of the world when I saw it suffering the painful disorder of this island. A blind fate, a vast pitiless mechanism, seemed to cut and shape the fabric of existence, and I, Moreau by his passion for research, Montgomery by his passion for drink, the Beast People, with their instincts and mental restrictions, were torn and crushed, ruthlessly, inevitably, amid the infinite complexity of its incessant wheels.

I'd like to read more H.G. Wells and I intend to return to this one again as well, possibly in a few weeks with S. My response to it next time may not be quite as visceral. Perhaps I'll see Prendick in a more appreciative light; he does makes an excellent narrator even though his passive nature infuriated me on my first reading.

They lay, opened and half read, all over her house

'I don't read as much as you,' said Scarlet.

'You should go down the High Street,' said Constance. 'You'd be amazed what you can pick up on the remainder counter for a song.'

'We've got no room for any more books,' said Scarlet. 'The shelves are full.'

'They say you can tell all about a person from looking at his books,' said Constance, who had become addicted to book-collecting since she had acquired a car-load of second-hand volumes from a fair in the Midlands. She had originally intended to resell them but found she had grown attached to them and had built shelves in her sitting-room. They lay, opened and half read, all over her house.

'I don't know what they'd make of ours,' said Scarlet. 'Brian only buys novels by those men, and I haven't bought a book for years--not since Elizabeth David, I don't think.'

'I can't read books by men,' said Constance. 'They will go on about their willies and chopping blondes to bits, and who cares?'

'I think they think we do,' said Scarlet.

'I don't think they do,' said Constance. 'I think they just can't really think about anything else.'

--Alice Thomas Ellis, Pillars of Gold

Friday, October 28, 2011

Caleb Williams

When the Classics Circuit announced its Gothic Lit Tour I thought I would need to take a pass on it. My sensibilities are more attuned with the Southern school of Gothic, Flannery and Faulkner, writers much too late for inclusion. Then my eyes snagged on Caleb Williams down at the bottom of the suggested titles list and I knew I'd be participating after all.

Caleb Williams had numbered among my tbrs since back in the winter, when I read what Rebecca West had to say about it:

"Once every five years or so I re-read two novels, which seem equally remarkable achievements. One is Thackeray's Vanity Fair. Everybody's heard of that. The other is Caleb Williams, by William Godwin, the philosophic radical whose political writings made a dent in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Nobody's heard of that. Yet I find it a great book, a serious, eloquent, important book with a great subject: it deals with authority, the authority of parents, guardians, teachers, God the Father, and asks the question can God the Father be forgiven for the existence of pain, can anything be made of the superior-inferior relationship. And it finds a perfect myth, a perfect plot for this discussion. Why is it not a recognised classic?"How could I not want to read a forgotten classic, a novel that the formidable Rebecca West could not manage to suck dry on her first go-through?

Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, published in 1794, on the heels of William Godwin's Political Justice from the previous year, is often regarded as its companion piece, a way of popularizing its political philosophy for those who had not read his treatise, a way of pointing out the defects in the English social system, in its justice system. Many see it as the first detective novel, the first thriller, or as one of the first novels to address abnormal psychology. Is Caleb an unreliable narrator? Could he be gay? Is there a connection between Godwin's novel and that of Frankenstein, his daughter Mary Shelley's better-known novel? Should the novel be placed squarely in with the Romantics or the Gothics or allowed to straddle both?

Lowly-born Caleb Williams, largely self-educated and orphaned at 18, is quickly taken on as secretary and librarian by country squire Ferdinando Falkland following his father's funeral. It is a wonderful position for Caleb, a young man of insatiable curiosity who loves books. All in the household and the surrounding area regard Falkland as a man of great benevolence and integrity. Caleb soon learns that Falkland can also be peevish and tyrannical, but believes these negatives proceed "rather from the torment of his mind than an unfeeling disposition."

One day Falkland accuses the unwitting Caleb of spying upon him, of wanting to ruin him. He says he'll trample him into atoms; later in the day he presses money into Caleb's hand by way of apology. Mr. Collins, the steward, tells Caleb a lengthy story that fills out the rest of volume I, one with elements that remind me a great deal of Trollope's The American Senator; a story that explains why the once outgoing and chivalrous Falkland has turned paranoid and gloomy: ultimately, he was publicly and physically insulted by, then suspected of murdering, another aristocrat in the community. It is this story with its parallels to Caleb and Falkland's future relationship, and, indeed, even the similarity of names between those in Collins' story and those who find their way into Caleb's own, that call into question the reliability of Caleb's narrative.

Falkland is cleared of suspicion when the aristocrat's former tenants, Hawkins and his son, are found with evidence connecting them to the murder; they are subsequently hanged. Caleb, however, becomes convinced that a man with Hawkins' principles would never stoop to murder. He begins to delight in mentally tormenting his benefactor, who he suspects framed the Hawkinses, until Falkland calls him on it. Caleb then declares himself "a foolish, wicked, despicable wretch." He begs to be punished, to be turned out of service, then declares his loyalty to, his lasting love for Falkland. Falkland keeps him on, although his own moods darken.

One day, while Falkland is off on one of his "melancholy rambles," a chimney fire blazes out of control and Caleb supervises the removal of household goods to the lawn. Caleb goes a bit nuts. With his mind, as he says, "raised to its utmost pitch," he seizes the opportunity to break into a trunk in Falkland's private apartment off the library, a trunk Caleb's long thought contains documents that will prove Falkland guilty of the suspected crimes.

Naturally, Falkland comes in and catches him in the "monstrous" act. "One short minute had effected a reverse in my situation, the suddenness of which the history of man, perhaps is unable to surpass." Falkland points a loaded pistol at Caleb's head, then throws it out the window to keep himself from firing. The situation leads Falkland to extract an oath of silence from Caleb, then confirm all his suspicions: he's guilty as sin just as Caleb's thought. He says Caleb's to remain in his service, but will from this point never receive his affection.

The second half of the novel concerns itself with Caleb's efforts to leave Falkland's household and the extent Falkland will go to persecute him. Caleb will find that while the reputation of a man of Falkland's standing in the community is defense enough against a murder charge, Caleb's own reputation can be destroyed easily by his social better. Falkland frames him as a thief and he is thrown into jail to await a nonspeedy trial. Eventually Falkland will provide Caleb with the means to break from jail, but he will be unable to escape from Falkland's ability to track and the lengths he will go to to undermine all efforts to make a new life for himself. Things will become quite Kafkaesque for awhile. Caleb will be the first (and the last!) to tell you how no one has suffered as much as he.

Godwin wrote two endings to Things As They Are, and both are often included in current editions of the novel. In the original, Caleb gets his day in court, but he's seen only as a man out for revenge; he's imprisioned again and appears to go mad. In the version Godwin chose to publish, there is more emotional resolution, with Falkland admitting his guilt and much mutual forgiveness of wrongs committed.

While I can see that there's enough meat on the bones of this story to bring one back for subsequent re-reads, I cannot say that I intend to return to it. Caleb feels so sorry for himself that I felt no need to do so myself. There was something so hinky in his desire to undercover his kindly employer's guilt out of nothing more than sheer curiosity instead of an actual sense that justice should be served that I often wanted to just slap him. Plus, there's the fact that I vastly preferred Collins' story within Caleb's story to Caleb's own. I'm firmly in the realism camp and there are tons more Trollope and Gissing novels for me to get to. And there's Vanity Fair. Yes, Rebecca, I've heard of that. But I still haven't read it.

Read another review of Caleb Williams at Aesop to Oz.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Surviving it all, a sort of bloggiversary post

I told myself I would resume blogging once the kitchen remodel was complete. I expected that to be in July, then August, okay then, September.

The floor was installed, not the day after Labor Day, as planned, but that week. The cabinets came in in stages; the cabinetmaker and I got along once we left the general contractor out of the picture, who had issues with returning phone calls to either of us.

I wasted a lot of vacation days being stood up by people who couldn't be bothered to tell me they weren't coming in that day even though it had been previously confirmed that they were indeed going to do just that.

I painted walls. I painted the ceiling, now stripped of its protective but icky popcorn, in both the kitchen and family room countless times with a roller before resorting to brush painting it twice which it seemed to mollify it into looking considerably less splotchy. My hand ached a lot.

Eventually, the last week in September, the granite went in, followed quickly by the sink and the gas cooktop and the electric/convection oven with a computer for its brain.

The oven intimidated me and I was planning on having L. read the manual and then tell me how it worked before I attempted anything when the guys decided to make cookies late at night.

And it seemed to me that maybe they ought to have read the manual when after 30 minutes the oven had managed to heat itself only to 190 degrees. I resorted to reading the manual myself, figured out how to put it on speed-preheat, and about ten minutes later the temperature reached 210 degrees and something inside the oven's brain exploded from all that excess heat. The resulting smoke was efficiently exhausted outside thanks to the new chimney hood.

|

| Me, behind the plastic used to protect the walls from falling ceiling popcorn. |

The oven flashed an 800 number at us and told us to call it, so we did, and that resulted in four visits, I believe, over three weeks from a two-man crew from a small appliance shop who would tell us different things were wrong each time they came out with a different motherboard or fan until they ran out of new parts to order that were under warranty. We then did what we would have done in the first place if we hadn't been following the oven's directives and called Lowes, from whom we'd bought it. The guy who came out did a diagnostic, came back five days later--this Tuesday actually-- with the necessary part, and while no one except the Lowes guy expected this to make a difference, expecially me, prone to frequent fatalist rants these days, the oven works beautifully now. I've made three loaves of pumpkin bread and two of sourdough and I'm feeling the need to swear off carbohydrates for awhile.

L. started a new job in August and he had to redo a lot of the plumbing done by the so-called professionals so it took him until yesterday to finish putting the hardware on the cabinets and drawers. He wore me down on the placement for the cabinets pulls so that they're two cm higher than I wanted them, but I wouldn't budge from the middle on the drawers, even though he wanted the pulls placed on the edge.

Still a lot to be done, mostly by us, but we're still waiting on the delivery of the glass shelves for the china cabinet (cabinetmaker's still too pissed at the general contractor to bother bringing them by) and I'm playing phone tag with the kitchen designer about when the backsplash is to be installed.

I love the new kitchen, I will post pictures as soon as the shelves and backsplash are in, but even if I didn't love it, I would NEVER go through another remodel. I'm too old for all the upheaval involved.

Monday the blog turned seven. I intended to post in honor of such an occasion, but we went out to dinner since it was also my birthday and then I had to sit around in a stupor afterwards until it wasn't too early to go to bed.

Next year I'll bake the blog a cake. I've got an oven now; I can do it. Y'all will all be invited to have a piece.

Thanks for being readers and my internet friends.

Tomorrow I'm actually posting a book review.

I know, I know. I don't quite believe it either.

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Smokin' Seventeen

by Wendy

Fans of Stephanie Plum’s escapades will not be disappointed by Janet Evanovich’s latest installment, Smokin’ Seventeen. Chapter one begins with a phone call from Grandma Mazur, who recounts a bizarre dream to Stephanie; moves to the Tasty Pastry Bakery, where Grandma Bella puts the eye on Stephanie; and ends at the site of the former bonds office with Joe Morelli, Vinnie, Connie, Mooner, and Stephanie stand, staring at parts of murder victim number one. As the novel unfolds, the reader is taken over familiar terrain: Yes, there are zany characters, such as 72-year-old FTA, Ziggy Glitch, who thinks he’s a vampire; yes, Grandma Mazur gets kicked out of a viewing; yes, Lula goes on yet another whacky diet; yes, Stephanie’s car blows up; and yes, Stephanie’s love life with cop boyfriend, Joe Morelli, is complicated by enigmatic hottie, Ranger.

Fans of Stephanie Plum’s escapades will not be disappointed by Janet Evanovich’s latest installment, Smokin’ Seventeen. Chapter one begins with a phone call from Grandma Mazur, who recounts a bizarre dream to Stephanie; moves to the Tasty Pastry Bakery, where Grandma Bella puts the eye on Stephanie; and ends at the site of the former bonds office with Joe Morelli, Vinnie, Connie, Mooner, and Stephanie stand, staring at parts of murder victim number one. As the novel unfolds, the reader is taken over familiar terrain: Yes, there are zany characters, such as 72-year-old FTA, Ziggy Glitch, who thinks he’s a vampire; yes, Grandma Mazur gets kicked out of a viewing; yes, Lula goes on yet another whacky diet; yes, Stephanie’s car blows up; and yes, Stephanie’s love life with cop boyfriend, Joe Morelli, is complicated by enigmatic hottie, Ranger. If you’re new to the series or haven’t been keeping up, you can still plunge in because narrator Plum briefs us on key bios and background. And, whether you’re new to the series or not, if you haven’t listened to any of the audio/CD/digital recordings, waste no time in checking one out from your local library. Be sure and select those narrated by C.J. Critt. Her characterizations, especially of Lula, are spot-on and have made me laugh out loud. Speaking of laughter, I’ve watched the movie trailer for One for the Money, the first book in the series, and it wasn’t funny. Where are those New Jersey accents? Why wasn’t someone like Cloris Leachman cast as Grandma Mazur? And if only Sandra Bullock weren't a little too old to be playing Stephanie . . . but I digress. Anyway, you can check out the trailer on http://movies.yahoo.com/movie/1810168438/video/26714574.

So, the bottom line is if you’re looking for standard Stephanie Plum fare, read or listen to Smokin’ Seventeen. If you’re like my sister, who’s tired of the franchise and the romantic tug-of-war, skip this one and wait to hear what the grapevine has to say about the next one. As for me, yes, it’s predictable and light, but the pleasure of reading a comic novel, especially one that is set in Trenton, NJ (across the river from Yardley, PA, where I lived for ten years and which does get a shout-out in one of the books) and sharing a Hungarian heritage with the protagonist is worth a few hours of my time.Sunday, September 25, 2011

Boys

by Wendy

At recess, in sixth grade,

we'd shoot out from school like marbles

The girls would go make dandelion chains,

play jump rope,

hopscotch with rock markers found in the grass,

where boys chased each other in PF Flyers,

or sometimes, chased us, swinging fat worms from pinched fingers

On the monkey bars, we practiced skin-the-cat,

legs upside down Vs, skirts and dresses and shoelaces dangling

over blacktop

We never fell

Boys hovered nearby like yellow jackets around jelly sandwiches,

eying our underwear

Fridays were marriage days on the playground

Girls who caught boys were married for the day

Whatever that meant

Whatever that means

Grown-up boys still play and chase and scare us,

Still thrilled by our underwear,

And still, like their playground selves, come Monday,

have cooties again

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Reading plans? I got 'em; or, H.G. Wells, Gissing, and the gang

Back in the early days of January, I stated that David Lodge's novel about H.G. Wells, A Man of Parts (reviewed this weekend in the Sunday Book Review), was the book I was most anxious to read in 2011. I ordered it as soon as it was available in the UK and, naturally, it remains unread, as do seven other books from my Top Ten Books to Read list.

I am of course too distractable to stick with any list of ten, but in this case I also put pressure on myself to delay its reading because I needed to earn the right to do so. My interest in Wells derives primarily because of my Rebecca West project, and it just seemed as if I ought to have read a bit more by him (I'd only read The Island of Doctor Moreau with the Slaves) and about him before rewarding myself with the Lodge.

So in August I read The Time Machine, which led to the other novel published this year with Wells as

Instead I opted to take a break from the science fiction and go with Ann Veronica, the 1909 novel regarded as a roman a clef based on his affair with the other other woman--besides West--to bear him a child outside his marriage to Jane: Amber Reeves.

So I'm tooling along quite happily with Ann Veronica yesterday, enjoying my time with this representation of the New Woman until Vee's involvement with the Suffragettes lands her in prison and she undergoes a radical 180 in her beliefs and expectations.

And I think: I'm reading George Gissing. I'm reading a George Gissing novel. And I take to the internet to see if anyone else has noticed this. Could be it's just your typical sneaky underhanded misogyny.

And while I may very well have read this fact before, I must have glossed right over it: George Gissing and H.G. Wells were friends (or, at least, frenemies. It depends on which camp, pro- or anti-Wells, that you're in). Wells was there at Gissing's death bed, force-feeding him beef broth and stealing his final words to use as a character's final words in Tono-Bungay. There's actually an out-of-print collection of Gissing and Wells' letters: I ordered it immediately.

So now I have to at least read the letters and Tono-Bungay before I proceed to A Man of Parts, as well as more Gissing. And I want to read more about the suffragettes--I've been planning to do that since reading A.S. Byatt's The Children's Book. I'll have a new book to add to my list in November--Susan Hertog's biography Dangerous Ambitions: Rebecca West and Dorothy Thompson: New Women in Search of Love and Power comes out then.

For anyone who finishes Ann Veronica and feels a bit bummed at how Wells brings Vee to such a conventional, second fiddle status by the end of the novel, take heart. Amber Reeves, Margaret Drabble tells us, accomplished much more with her life than Wells would imagine for her on the page.

I'll have to resort to ILL to get my hands on Reeves' novels, but I will. Just as soon as I get caught back up with my Drabbles.

Sunday, August 28, 2011

she walks in beauty: A Woman's Journey Through Poems

A close girlfriend of mine gave me this book when we met at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. this summer. On the ride home on the Metro, I thumbed through it in anticipation. I am a woman! I am halfway through my journey (If I live to be a hundred, which is likely considering the shelf life my body must have, considering all the processed food I eat)! I write poetry! This is perfect! A book of poems by and about women!

A close girlfriend of mine gave me this book when we met at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. this summer. On the ride home on the Metro, I thumbed through it in anticipation. I am a woman! I am halfway through my journey (If I live to be a hundred, which is likely considering the shelf life my body must have, considering all the processed food I eat)! I write poetry! This is perfect! A book of poems by and about women!Except it's not. I read the first poem, "She Walks in Beauty." By Lord Byron. Yes, by a man. And he has plenty of company. Of the nearly 200 entries, approximately a third are written by men. Now, I have nothing against male writers, I just thought this book could have been a wonderful opportunity to showcase female poets exclusively, especially considering the subject matter.

The collection, selected and introduced by Caroline Kennedy, promises to be, as Kennedy writes in the introduction, " . . . an anthology of poems centered around the stages of a woman's life . . .." And, aptly, she walks in beauty is divided into several sections, including, "Falling in Love," "Breaking Up," "Marriage," "Motherhood," "Work," and "Growing Up and Growing Old," among others. There are classic poems, such as "To My Dear and Loving Husband," by Anne Bradstreet and contemporary poems, such as, "PS Education" by Ellen Hagan. There is a nice diversity in the collection, with poems by Dominican-American Julia Alvarez ("Hairwashing," Woman's Work," and "Woman Friend"), African-American Parneshia Jones ("Bra Shopping"), Arab-American Naomi Shihab Nye ("My Friend's Divorce"), among others. There are humorous poems, such as Dorothy Parker's "Sympton Recital" and touching poems, such as Jo McDougall's "Companion." (One of my favorites.) There are poems about heterosexual love, lesbian love, motherly love, sisterly love, and yes, chocolate love. When I finished reading the last poem, I decided that, although I consider the title misleading, ultimately, Kennedy's book is a nice addition to my collection of poetry books.

by Jo Mcdougall

When Grief came to visit,

she hung her skirts and jacket in my closet.

She claimed the only bath.

When I protested,

she assured me it would be

only for a little while.

Then she fell in love with the house,

repapered the rooms,

laid green carpet in the den.

She's a good listener

and plays a mean game of Bridge.

But it's been seven years.

Once, I ordered her outright to leave.

Days later

she came back, weeping.

I'd enjoyed my mornings,

coffee for one;

my solitary sunsets,

my Tolstoy and Moliere.

I asked her in.

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

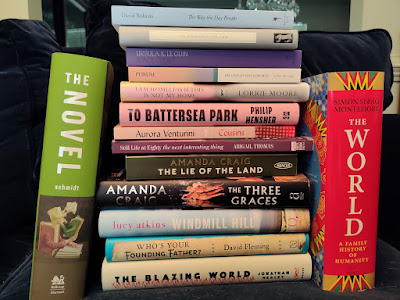

Latest stockpile

Granted, I haven't showcased my book purchases since early April, but I was so horrified once I'd gathered (most of) the newbies together for the above photo op, that I cancelled three Amazon pre-orders. I don't need to acquire books for awhile, even if I do have gift certificates.

(Please note that the first three titles tell a story.)

Left stack:

Jeanne Darst's Fiction Ruined My Family. These days I rarely try for books at LibraryThing, so I was delighted when I won a galley of this memoir. Should make a great tie-in with Reading My Father and Yossarian Slept Here.

Sarah Bakewell's How to Live. Talked myself out of getting this from the library, so that I wouldn't feel that I needed to rush through it.

Jacqueline Winspear's Among the Mad. From the free books shelf in the staff lounge. Guess I should read at least some of the earlier Maisie Dobbs' before I start this.

Harry Mulisch's The Discovery of Heaven. I'd hoped to read along with Iris back in June, but quickly realized it just wasn't the time for me to start a book this size.

Andrew Burstein and Nancy Isenberg's Madison and Jefferson. Someone recommended David McCullough's biography of Truman to me today; I in return recommended Ron Chernow's Alexander Hamilton. I need to devote more actual time to biographies instead of merely intending to.

Amitav Ghosh's River of Smoke. I haven't even read Sea of Poppies yet!

Dale Peterson's The Moral Lives of Animals. A review copy.

David Lodge's A Man of Parts. My most anticipated book of the year. Why didn't I started this immediately? Now I'm planning to have an H.G. Wells month.

Middle stack:

Annabel Lyon's The Golden Mean. The Slaves of Golconda will be discussing this on Sept. 30.

Jane Rogers' The Testament of Jessie Lamb. Made the Booker longlist so I thought I'd give it a try.

Stephane Audeguy's The Theory of Clouds. A French novel recommended at book club.

Felix J. Palma's The Map of Time. Steampunk. Another book for the potential H.G. Wells month.

Ron Rash's Saints at the River. Rash is my go-to for Appalachian fare.

Anne Enright's The Forgotten Waltz. Was surprised that this didn't make the Booker longlist. Have high expectations here since I loved The Gathering.

Tessa Hadley's The London Train. I like Hadley.

Kate Christensen's The Astral. Haven't read Christensen since The Epicure's Lament, which I loved. Another book I have high expectations for.

China Mieville's Embassytown. R. gave me this for Mother's Day.

Philip Hensher's King of the Badgers. Loved The Northern Clemency.

Right stack:

Tim Pears' Disputed Land. Lots of buzz about this at Book Balloon.

Jane Harris' Gillespie and I. I've not read Harris before.

Buck Brannaman's The Faraway Horses. A gift from C. for catsitting.

Patrick DeWitt's The Sisters Brothers. And we finally reach a book that I've read. I even read it immediately after receiving it! I'm pulling for the western to win the Booker! Plus, this has the best cover ever.

John Sayles' A Moment in the Sun. Could I get this read in a month if I read nothing but? Jeez, it's huge.

David Foster Wallace's The Pale King. Need to read the essays and short stories first.

Joe Scco's Footnotes in Gaza. Another freebie from the staff lounge. I have Palestine in progress.

Sunday, August 07, 2011

Books read in July

I always like the Nick Hornby-style end-of-month posts outlining that month's reading and I'm trying to develop the habit of writing down my impressions, instead of simply appreciating when others do.

Here's what I completed in July (now that we're in the second week of August), with the most recent first:

William Styron's Lie Down in Darkness

William Styron's Lie Down in DarknessBeautiful, alcoholic Peyton Loftis, the sole remaining daughter of the estranged Milton and Helen Loftis, kills herself in New York; her remains are brought home by train to the Virginia Tidewater to be buried. The dark humor of Peyton's funeral procession is interrupted by flashbacks revealing just how deep the dysfunction runs in this mid-20th century family. Everyone feels a victim; everyone behaves badly. Always.

The last chapter is an unholy Quentin Compson/Septimus Smith amalgamation, told in a Molly Bloom narration style. It comes across as more derivative than influenced by, although the fact that Styron managed a novel like this at a mere 26 years of age is awfully impressive. Wendy and I decided to read this after finishing Alexandra Styron's memoir, Reading My Father, back in June. I'm glad I read it and I'll definitely be reading more Styron, but I think I'd better space them out since they're so dense and dark.

Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf.

Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf.By now it should be a well-established fact that I have issues where thrillers, particularly thrillers dealing with the occult, are concerned. I can't suspend the little voice inside my head which pipes a persistant "This is stupid" refrain, although I will periodically give one a try.

So you may be surprised by what I say now: I loved this.

(Granted, at least theoretically I've always been in the werewolf camp, even before my friends and I perfected The Werewolf and The Repossessed Werewolf facial expressions/hand gestures back in high school--yes, yes, we were immature for our age. Not that I ever read much about them or saw many werewolf movies, but just the fact that they were not vampires put me on their side. And we won't even get into how I was known for my wolf howl back in elementary school.)

I thought This is stupid only once while reading about werewolves and vampires and those who hunt them/rescue them and I fully intend to read the sequel. I was too busy enjoying Jacob Marlowe getting from I still have feelings but I'm sick of having them. Which is another feeling I'm sick of having. I just . . . I just don't want any more life to I've stopped abstracting. This is love: You stop bothering about the universal, the general, get sucked instead into the local and particular: Theory and reflection are delicate old uncles bustled out of the way by the boisterous nephews action and desire. Themes evaporate, only plot remains.

Mary Doria Russell's Dreamers of the Day

Mary Doria Russell's Dreamers of the DayThis isn't of the same caliber of The Sparrow or Doc, but it served my purpose, which was to learn a bit more about how the modern Middle East came about, and have a bit of fun in the process. Plus, it has a dead narrator, a device I always get a kick out of. Caught a whiff of Kevin Brockmier's The Brief History of the Dead in the afterlife, but I don't know if Russell intended it.

Stephen Budiansky's The Bloody Shirt: Terror After the Civil War.

Stephen Budiansky's The Bloody Shirt: Terror After the Civil War.A bald fact: more than three thousand freedman and their white Republican allies were murdered in the campaign of terrorist violence that overthrew the only representatively elected governments the Southern states would know for a hundred years to come. Among the dead were more than sixty state senators, judges, legislators, sheriffs, constables, mayors, county commissioners, and other officeholders whose only crime was to have been elected. They were lynched by bands of disguised men who dragged them from cabins by night, or were fired on from ambushes on lonely roadsides, or lured into a barroom by a false friend and on a prearranged signal shot so many times that the corpse was nothing but shreds, or pulled off a train in broad daylight by a body of heavily armed men resembling nothing so much as a Confederate cavalry company and forced to kneel in the stubble of an October field and shot in the head over and over again, at point-blank.

I knew from growing up in the South that generations had been taught a glossed over version of Reconstruction: Yes, the KKK caused problems but things wouldn't have been nearly so bad if it hadn't been for the carpetbaggers; let's move right along to the next chapter in the text and then we'd all go see Gone With the Wind a couple of times the next time it played at the theater and take it as holy writ. Budiansky talks about this, in case your formative years went lighter on the mythology than my own. Otherwise, the situations described in this book were revelatory.

And heartbreaking.

I'll leave it at that.

Linda Grant's We Had It So Good

Linda Grant's We Had It So GoodMy first Grant, and one of the books expected by many to at least be longlisted for the Booker; I loved it and wish it had been. My older siblings were first-wave baby boomers, same as the characters here, while I came along 15 years later at the tail end of the generation, and this all seemed very true to the times. But even more, I loved the book for its exploration of how the stories we're told by our families that we accept as truth are often anything but.

Brad Watson's Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives

Brad Watson's Aliens in the Prime of Their LivesI finished the titular story in this collection of stories in early July, although I started the book back in the spring. Some I enjoyed quite a bit, others left little impression, perhaps because I was at the height of my kitchen remodel mania during May and June. This was a PEN/Faulkner finalist, but one the book blogging community seems to have overlooked. Give it a try when you're in the mood for something a bit weird.

Sunday, July 31, 2011

Contemporary Lit

What if writers texted their words

lol omg

Would we remember them?

What if Hemingway were a waterman

shucking oysters instead of words

setting aside the good ones

to slide Chesapeake damp down our throats

to the sound of open shells falling on open shells

And what if Frost had owned a GPS

to map the road not taken

Would he have taken it?

Sunday, July 24, 2011

Reading My Father by Alexandra Styron

Just as the sea, by turns rageful and indifferent, takes hold of those caught in it, so William Styron did with his family, especially his youngest daughter, Alexandra, whose recent memoir, Reading My Father, tells the story of their relationship. It was a relationship dictated by her father’s ferocity, aloofness, and depression, one that she writes of honestly and eloquently.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Mothering narratives

You carry a baby in the womb for nine months and then, when they're grown up, they call you collect, when they remember. She has her own life. And that's okay. I've learned to be patient. "Teach only love for that is what you are." The ups and downs; I live with it. And I've got a lot ahead of me and a lot to be proud of. I know: she is the reason I was born.

--Mona Simpson, Anywhere But Here

Back in the spring, after my mind had settled into its All Things Kitchens All the Time groove, with room for nothing else, LomaGirl left this request in comments:

I'm looking for mothering narratives- novels, essays, short stories, memoirs. Can you think of any books that you would classify as this? I would really appreciate some help!

And I immediately thought of the ending to the Mona Simpson; Lorrie Moore's "People Like That Are the Only People Here"; memoirs by Shirley Jackson and Louise Erdrich and Anne Lamott; Sue Miller's The Good Mother (although I never thought she was); Jill in Robert Boswell's Crooked Hearts, trying to keep the family together after the eldest son literally destroys their house; the mother of the autistic boy in Anna Mitgutsch's Jakob; Pearl Tull in Anne Tyler's Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant; the two moms in Richmal Crompton's Family Roundabout; the mom in Joanna Cannan's Princes in the Land; and then, my mind went blank.

Since then:

Doris Lessing's The Sweetest Dream

A.S. Byatt's The Children's Book

Rebecca West's The Fountain Overflows

Anne Tyler's Breathing Lessons, Searching for Caleb, etc.

Jackie Lyden's Daughter of the Queen of Sheba

I think I would classify most of my reading in the They fuck you up, your mum and dad vein, or else the good mothers of literature outside Demeter have failed to leave a mark on me.

Anyone else have some suggestions for LomaGirl? Jackie compiled her own list of the Best Books About Motherhood a couple weeks back and received some suggestions as well (I was particularly chagrined to realize I'd forgotten about Roxanna Robinson's Cost), but I feel we've only touched on the surface of the mothering narratives out there.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Book orientation

I never did this particular meme when it was so popular back in the spring. Figured now was the time for it. . .

The book I'm currently reading William Styron's Lie Down in Darkness. With Wendy. Summer is the perfect time for a Southern tale of family dysfunction. Will the second-person narrator that opened the book make a reappearance? Only I would hope so.

The last book I finished Mary Doria Russell's Dreamers of the Day. I loved, loved, loved The Sparrow, but hated its sequel with an equal passion (don't ask why; I don't remember). Refused to even look at another Russell until Doc came along, which I couldn't pass up because it was a western. I loved, loved, loved it. Now Russell is officially off my ignore list.

The next book I want to read Two books, actually. Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf and Peter Carey's Parrot and Olivier in America. The Carey is for book club and the Duncan, waiting for me at the library, has a long waiting list so I won't be able to renew it.

The last book I bought Nuances here. Last book purchased was Stephane Audeguy's The Theory of Clouds. Last book downloaded to the Kindle was Vladimir Sorokin's Ice Trilogy. The last book bought that has shown up in my mailbox is Tim Pears's Disputed Land. Still waiting for Jane Harris's Gillespie and I. I bought the Harris before the Audeguy and the Pears. Such is life when you buy books through the Book Depository.

The last book I was given C. gave me a copy of Buck Brannaman's The Faraway Horses. (All horses seem very faraway right about now.)

The last book I checked out from the library From the public library, Roger Zelazny's Lord of Light. From the university library, Bonnie Jo Campbell's Once Upon a River.

What was inside the last package a publisher/publicist sent me Five galleys from Random House. The one I'm most likely to read is Aravind Adiga's Last Man in Tower. I doubt I'll have it read by its September pub date, though.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Doc by Mary Doria Russell

Oh sure, I'd heard of Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp, the shoot-out at the OK Corral, and Tombstone, Arizona before reading Doc by Mary Doria Russell, but they were names and places that held no substance, like placeholders at a dinner party, not the guests themselves. Russell's gift in this work of historical fiction is a well-told story tethered in fact, but allowed to graze.

Rooted in what facts the author could unearth (she writes of her source material in the notes at the end of the book), the novel takes us on the detailed journey of Dr. John Henry (Doc) Holliday whose fate rests not with Russell, but with history. What makes Doc so engaging is Russell's portrayal not of "[A] cold and casual killer," as he was caricatured by the newspapermen of his day, but of a man who is at the mercy of tuberculosis; a man who is an accomplished pianist, dentist, and card shark; a man in love with a whore; a man who is by turns gracious and enraged; and a man whose relationship with the Earp brothers is not so infamous as what legend would have us believe.

Doc is cleverly divided into chapters using poker terms--poker and a game called faro are integral to the story. And just like in cards, the author lays out her cast of characters in a section called "The Players," where she differentiates the fictional ones by putting their names in italics. This section is a particularly helpful resource.

My only complaint is the novel leaves off in April, 1879, just as Doc is about to leave Dodge City, with the final chapter focusing on Kate, Doc's lover, and summarizing the rest of the main characters' lives. I only hope Russell considers expanding that short narrative into a full-fledged follow-up novel. Please, Mary, play one more hand.

Saturday, July 16, 2011

I'm back and I have big news

Okay, actually, I'm just sort of back. We're in the midst of a kitchen remodel, a kitchen remodel that I'd hoped would be finished just about now. But, as these things often go, it's taking longer than expected. The cabinetmaker (the second cabinetmaker; the first one hightailed after he was discovered stealing from the company) is now saying he'll have the cabinets completed in three weeks, but the kitchen designer is skeptical and advised me to plan on it taking more like five. Since we're doing the demolition ourselves, including removing the old soffits and ceiling; installing the recessed lights; replacing the ceiling and sheetrocking the new soffits (which should not resemble jutting eyebrows this time around), repainting the kitchen and the connecting family room, putting down subflooring, and no doubt a few other things I'm forgetting, we probably do need five more weeks instead of three. At least I can wean myself off the kitchen porn now that everything's been selected; that should free up some time to resume blogging. I have spent much more time than is healthy on kitchen porn the past three months and I'm tired of second guessing all my choices.

But the big news I have has nothing to do with the kitchen. You've no doubt seen me mention my good friend W. on occasion, with whom I've been reading and discussing books for a good twenty years. Last year Wendy helped me get through Ulysses; this year we've read The Waves and Skippy Dies and A Visit from the Goon Squad and In Persuasion Nation and Reading My Father as well as a whole slew of Somerset Maughams just last month. We're in the early pages of William Styron's Lie Down in Darkness right now.

Wendy's an accomplished writer, of both fiction and poetry, and she's currently hard at work on a novel. I am thrilled to report that she has agreed to become a co-writer here on the blog. Her first review will post Sunday evening and she's hoping to keep to an early-in-the-week schedule hereafter, although I told her it's perfectly okay to post whenever and however often she desires.

I've given Wendy a long annotated list of blogs that I expect she'll enjoy as much as I do. Since she's totally new to blogging, though, it may take her awhile to make the rounds and keep you all straight in her mind. Please feel free to stop by over the next few days and introduce yourselves to her. I can't think of a better way of helping her to feel a part of this wonderful book blogging community.

Thursday, May 05, 2011

From the inside-out

--Joshua Hardina, Smiling With Gritted Teeth

Wednesday, May 04, 2011

Is that you, or a bot?

--Andy Isaacson, Are You Following a Bot?

Monday, April 11, 2011

Library Haul

I cannot possibly get to them all, but I'm going to try!

Journey Into the Past. Stefan Zweig.

The Last Brother. Nathacha Appanah

The Secret Lives of Baba Segi's Wives. Lola Shoneyin

The Universe in Miniature in Miniature. Patrick Somerville

Emerald City and Other Stories. Jennifer Egan

Model Home. Eric Puchner

Thirteen Orphans. Jane Lindskold

Father of the Rain. Lily King

Red Hook Road. Ayelet Waldman

Poems. Elizabeth Bishop

Never Say Die: The Myth and Marketing of the New Old Age. Susan Jacoby

Wish You Were Here. Stewart O'Nan

The Illumination. Kevin Brockmeier

When the Killing's Done. T.C. Boyle

Ship Breaker. Paolo Bacigalupi

The Empty Family. Colm Toibin

The Collected Stories. Grace Paley

A bang, not a whimper

Two months into L.'s retirement, and I'm finished with the stockpiling of books. No more book purchases! Or at least, no purcha...

-

(See also Musee des Beaux Arts ) As far as mental anguish goes, the old painters were no fools. They understood how the mind, the freakiest ...

-

When I finished Kevin Brockmeier's A Brief History of the Dead last spring I immediately did a search to see if the Coca-Cola Corp. had...