From Jonathan Franzen's delightful review of Alice Munro's

Runaway:

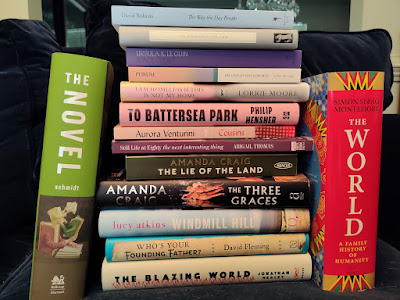

"McGrath's prejudice is shared by nearly all commercial publishers, for whom a story collection is, most frequently, the distasteful front-end write-off in a two-book deal whose back end is contractually forbidden to be another story collection. And yet, despite the short story's Cinderella status, or maybe because of it, a high percentage of the most exciting fiction written in the last 25 years -- the stuff I immediately mention if somebody asks me what's terrific -- has been short fiction. There's the Great One herself, naturally. There's also Lydia Davis, David Means, George Saunders, Lorrie Moore, Amy Hempel and the late Raymond Carver -- all of them pure or nearly pure short-story writers -- and then a larger group of writers who have achievements in multiple genres (John Updike, Joy Williams, David Foster Wallace, Joyce Carol Oates, Denis Johnson, Ann Beattie, William T. Vollmann, Tobias Wolff, Annie Proulx, Michael Chabon, Tom Drury, the late Andre Dubus) but who seem to me most at home, most undilutedly themselves, in their shorter work. There are also, to be sure, some very fine pure novelists. But when I close my eyes and think about literature in recent decades, I see a twilight landscape in which many of the most inviting lights, the sites that beckon me to return for a visit, are shed by particular short stories I've read.

"I like stories because they leave the writer no place to hide. There's no yakking your way out of trouble; I'm going to be reaching the last page in a matter of minutes, and if you've got nothing to say I'm going to know it. I like stories because they're usually set in the present or in living memory; the genre seems to resist the historical impulse that makes so many contemporary novels feel fugitive or cadaverous. I like stories because it takes the best kind of talent to invent fresh characters and situations while telling the same story over and over. All fiction writers suffer from the condition of having nothing new to say, but story writers are the ones most abjectly prone to this condition. There is, again, no hiding. The craftiest old dogs, like Munro and William Trevor, don't even try.

"HERE'S the story that Munro keeps telling: A bright, sexually avid girl grows up in rural Ontario without much money, her mother is sickly or dead, her father is a schoolteacher whose second wife is problematic, and the girl, as soon as she can, escapes from the hinterland by way of a scholarship or some decisive self-interested act. She marries young, moves to British Columbia, raises kids, and is far from blameless in the breakup of her marriage. She may have success as an actress or a writer or a TV personality; she has romantic adventures. When, inevitably, she returns to Ontario, she finds the landscape of her youth unsettlingly altered. Although she was the one who abandoned the place, it's a great blow to her narcissism that she isn't warmly welcomed back -- that the world of her youth, with its older-fashioned manners and mores, now sits in judgment on the modern choices she has made. Simply by trying to survive as a whole and independent person, she has incurred painful losses and dislocations; she has caused harm.

"And that's pretty much it. That's the little stream that's been feeding Munro's work for better than 50 years. The same elements recur and recur like Clare Quilty. What makes Munro's growth as an artist so crisply and breathtakingly visible -- throughout the ''Selected Stories'' and even more so in her three latest books -- is precisely the familiarity of her materials. Look what she can do with nothing but her own small story; the more she returns to it, the more she finds.

This is not a golfer on a practice tee. This is a gymnast in a plain black leotard, alone on a bare floor, outperforming all the novelists with their flashy costumes and whips and elephants and tigers.

''The complexity of things -- the things within things -- just seems to be endless,'' Munro told her interviewer. ''I mean nothing is easy, nothing is simple.''

"SHE was stating the fundamental axiom of literature, the core of its appeal. And, for whatever reason -- the fragmentation of my reading time, the distractions and atomizations of contemporary life or, perhaps, a genuine paucity of compelling novels -- I find that when I'm in need of a hit of real writing, a good stiff drink of paradox and complexity, I'm likeliest to encounter it in short fiction. Besides ''Runaway,'' the most compelling contemporary fiction I've read in recent months has been Wallace's stories in ''Oblivion'' and a stunner of a collection by the British writer Helen Simpson. Simpson's book, a series of comic shrieks on the subject of modern motherhood, was published originally as ''Hey Yeah Right Get a Life'' -- a title you would think needed no improvement. But the book's American packagers set to work improving it, and what did they come up with? ''Getting a Life.'' Consider this dismal gerund the next time you hear an American publisher insisting that story collections never sell.