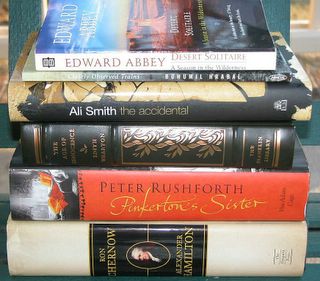

2005's Top Ten Favorite Books:

Pinkerton's Sister by Peter Rushforth

Closely Observed Trains by Bohumil Hrabal

The Accidental by Ali Smith

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow

Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey

The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls

The Highest Tide by Jim Lynch

The History of Love by Nicole Krauss

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

I completed 77 books this year: 47 novels, 13 works of nonfiction, eight collections of short stories, six plays and three books of poetry (I counted The Odyssey in with the novels. Sue me). I read 12 works that I consider classics, and I reread Peter Shaffer's Equus; William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying; E.C. Spykman's four children's novels; Walter Miller's A Canticle for Leibowitz; Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee's The Night Thoreau Spent in Jail; Joan Didion's Play It As It Lays; Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter; and Gabriel Garcia Marquez' Chronicle of a Death Foretold. I'd reread at least eight of those previously and am apt to do so again.

I left several works of nonfiction unfinished and would like to return to them at some point next year. I intended to read 365 stories this year, but reached only 200. I did not read Ulysses, which I'd told myself for years that I would read when I was 45, but I did read Don Quixote instead and so therefore totally absolve myself of all the prior years of lying. Maybe I'll read it in 2006—since I'm losing neural connections at an alarming clip, it really is one I need to get around to before it's too late.

I've enjoyed reading everyone's reading plans for next year: Gibbon, Dickens, Shakespeare and sensibly all over the map. Ella has already daringly resolved what her first ten books of the year will be and Sherry's listed an extensive number to draw from. Danielle added her stats and resolutions this afternoon. But since I cannot even stick with the little monthly resolves that I make, let alone one that should guide me for an entire year, I'll stick with Randall Jarrell and Mental Multivitamin and promise to "Read at whim! Read at whim!" in the coming year.

(That said, I have put together a list of 21 books at Library Thing-- under the name pagesaregonnaturn-- that I ought to read in 2006, fully realizing I probably won't.)

Happy New Year and happy reading!