When writing is great, Mitchell told me of the books he loved as a reader, “your mind is nowhere else but in this world that started off in the mind of another human being. There are two miracles at work here. One, that someone thought of that world and people in the first place. And the second, that there’s this means of transmitting it. Just little ink marks on squashed wood fiber. Bloody amazing.”

--"David Mitchell, the Experimentalist," Wyatt Mason interview with David Mitchell

Saturday, June 26, 2010

Monday, June 21, 2010

A sign of maturity?

Crossing campus this morning I heard the sound of some creature scrounging about in the bottom of a trash can. Raccoon? Feral cat? 'Possum? Large rat? While I did stop for a few moments to consider the possibilities, I did. not. kick. the. can.

And so the mystery remains.

And so the mystery remains.

Thursday, June 17, 2010

Now or then?

Do you prefer reading current books? Or older ones? Or outright old ones? (As in, yes, there’s a difference between a book from 10 years ago and, say, Charles Dickens or Plato.)

Last year, 55 percent of my reading was of books published within the last year; it was 53 percent in 2008. I'm a little less than 50 percent so far this year, thanks in large part to the 15 Books/15 Days project when I was drawn to the skinniest, not necessarily the newest and shinest, books on my shelves.

Even before blogging, which definitely brings out my competitive (Must. Read. This. First) side, I'd have to say I had an established tendency of reaching for the new hardback instead of the used paperback on its nth printing. This is in large part to support the writers who may not get a chance to publish again if no one buys their books now, and, of course, because I happen to enjoy these books.

But I also enjoy older books and definitely don't believe that because something is new it is automatically a better read or more worthy than what's come before; reading at whim merely leaves me more susceptible to being diverted away from books of merit (or longevity on my shelves) because of buzz.

And I am becoming more and more anti-buzz and marketing--at least inside my head; I'll have to see how well it plays out in my actual reading in the months ahead. No offense, but I don't want my literary DNA to be just like yours! I would like to read more classics, more books from the first half of the 20th century. I would like to buy fewer books as well: my shelves are overloaded.

Whether I can do this and still hang out with book bloggers remains to be seen.

Booking Through Thursday

Last year, 55 percent of my reading was of books published within the last year; it was 53 percent in 2008. I'm a little less than 50 percent so far this year, thanks in large part to the 15 Books/15 Days project when I was drawn to the skinniest, not necessarily the newest and shinest, books on my shelves.

Even before blogging, which definitely brings out my competitive (Must. Read. This. First) side, I'd have to say I had an established tendency of reaching for the new hardback instead of the used paperback on its nth printing. This is in large part to support the writers who may not get a chance to publish again if no one buys their books now, and, of course, because I happen to enjoy these books.

But I also enjoy older books and definitely don't believe that because something is new it is automatically a better read or more worthy than what's come before; reading at whim merely leaves me more susceptible to being diverted away from books of merit (or longevity on my shelves) because of buzz.

And I am becoming more and more anti-buzz and marketing--at least inside my head; I'll have to see how well it plays out in my actual reading in the months ahead. No offense, but I don't want my literary DNA to be just like yours! I would like to read more classics, more books from the first half of the 20th century. I would like to buy fewer books as well: my shelves are overloaded.

Whether I can do this and still hang out with book bloggers remains to be seen.

Booking Through Thursday

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

Friday, June 04, 2010

God vs. the multiverse

"Then I guess your CD player and credit cards stop working."

"I don't have a CD player or a credit card."

I grin at him. "Yes, but you know what I mean. Real technology is built on quantum physics. Engineers have to learn it. I mean, it is nuts, but it works out there in the real world."

"God or the multiverse," says Heather. "Which one would you choose?"

"I'm not happy with either of them," I say. "But probably God--whatever that actually means. Call it the Thomas Hardy interpretation: I'd rather have something out there that means something than feel like I exist in a vast ocean of pure meaninglessness."

"What about you, Adam?"

"God," he says. "Even though I thought I'd given up all that." He smiles without showing his teeth, as if doing more with his mouth would break his face. "No, it does make sense: the idea of an external consciousness. I prefer that anyway, given this choice."

"Oh well, I'm on my own then with the multiverse," says Heather.

"You're never alone in the multiverse," I say.

"Ha, ha," she says. "Seriously, I can't believe that God made life, not with the research I'm doing. I mean the evidence just isn't there. And I get so many threatening letters from creationists that I just can't align myself to them in any way."

"I don't think this means aligning yourself with creationists," I say. "Surely some external being could have sparked the very beginning of the universe and then everything else just evolved as scientists think it did."

Although as I say this I think: via Newtonian cause and effect, and I realize that this is at odds with the idea of a quantum universe, and I suddenly don't know what to say.

--Scarlett Thomas, The End of Mr. Y

Thursday, June 03, 2010

The Mountain Lion

There had been a big snowfall on Thursday and there had been no thaw. The sun was warm on the slopes and mesas and brilliant in the branches of the evergreens, but the air was cold and the wind was raw in the unprotected clearings. Uncle Claude said it might drop to twenty below that night. They had got the ladybugs --Uncle Claude scraped them up with his hunting knife to Molly's exasperation for she used a spatula which seemed more humane and also more scientific -- and had started down. Uncle Claude was the first to get to the opposite bank of the gulch and just as Ralph and Molly began the ascent, he turned around and motioned them to come quietly. It was an easy climb and the path was deep in snow so that they made no sound. Once Molly broke off an ice-covered twig on a chokecherry bush but the noise was slight. Their uncle stood absolutely still, watching something. He had moved into the cover of a small deformed scrub oak laden with snow and he beckoned them to join him. They stepped carefully in his boot-prints, not seeing yet what he did. Then, when they were beside him, he pointed to the east side of the mesa and there they saw the mountain lion standing still with her head up, facing them, her long tail twitching. She was honey-colored all over save for her face which was darker, a sort of yellow-brown. They had a perfect view of her, for the mesa there was bare of anything and the sun illuminated her so clearly that it was as if they saw her close up. She allowed them to look at her for only a few seconds and then she bounded across the place where the columbines grew in summer and disappeared among the trees. Her flight was lovely: her wasteless grace and her speed did not make Molly think immediately of her fear but of her power. When you saw a running deer, you were conscious only of its instinct to flee danger. The lion had sensed peril and yet they, the watchers, sensed peril in her, under her tawny hide, in the way her tail had moved against the glint of the snow, in the way she streaked across the flat land. Molly shivered to think she might now have climbed a tree like a tame cat and might be sitting there observing them with large green eyes.

--Jean Stafford, The Mountain Lion

--Jean Stafford, The Mountain Lion

Wednesday, June 02, 2010

Proposed Summer Reading and A Random Question

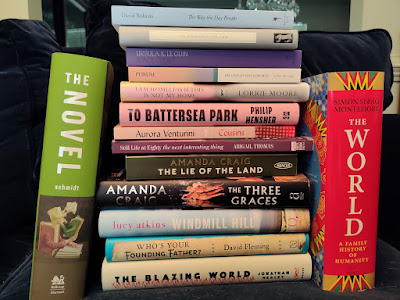

As best I can tell I skipped posting a summer reading list last year--I just talked about inactivating all the books on hold for me at the public library (and some of those holds are still inactivated: the guilt I deal with on a daily basis) so that I could read some of the ones I already owned. Above's the bulk of the books I hope to get through this summer. I of course want to read the new Justin Cronin, the new biography of E.M. Forster, and whatever will turn out to be the next selection for the Slaves and the newly-formed book club at work, but I don't have any of those on hand for the photo op.

The official Books of Summer 2010 are:

George Gissing's Demos. My Victorian lit for the summer.

Scarlett Thomas's The End of Mr. Y. I love some quantum physics in my fiction. Just started it last night.

J.C. Hallman's In Utopia. Advanced proofs; it's being published in August.

Jean Stafford's The Mountain Lion. NYRB is republishing this over the summer; I'm making do with an older University of New Mexico edition rescued from Compact Shelving.

Dorothy Canfield's The Home-Maker and Leonard Woolf's The Wise Virgins. Still more rescues from Compact Shelving instead of those nice Persephone editions everyone else has been reading.

J.G. Farrell's Troubles. I'm a little worried it'll get recalled before I get it read, but maybe no one else at the university is interested in the Lost Booker.

James Joyce's Ulysses. W. and I intend to have this finished by Labor Day. (I'm currently in the Circe chapter.)

Rebecca West's This Real Night. For my too-long-neglected Rebecca West project.

Wallace Stegner's The Big Rock Candy Mountain.

J.D. Hallman's The Hospital for Bad Poets.

Mary Lee Settle's Know Nothing.

Doris Lessing's The Sweetest Dream.

Doris Betts' The Scarlet Thread.

Maggie O'Farrell's The Hand that First Held Mine. Review copy.

Tom Rachman's The Imperfectionists.

Julie Orringer's The Invisible Bridge. My most recent purchase.

Justin Cronin's The Passage.

Wendy Moffat's A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E.M. Forster.

And my random question: Are there any extroverts who prefer character over plot in their reading? I know some introverts who prefer plot over character, but I can't come up with any extroverted acquaintances who prefer riding a character's thought waves over watching the character pick up the surfboard and head to the beach.

The official Books of Summer 2010 are:

George Gissing's Demos. My Victorian lit for the summer.

Scarlett Thomas's The End of Mr. Y. I love some quantum physics in my fiction. Just started it last night.

J.C. Hallman's In Utopia. Advanced proofs; it's being published in August.

Jean Stafford's The Mountain Lion. NYRB is republishing this over the summer; I'm making do with an older University of New Mexico edition rescued from Compact Shelving.

Dorothy Canfield's The Home-Maker and Leonard Woolf's The Wise Virgins. Still more rescues from Compact Shelving instead of those nice Persephone editions everyone else has been reading.

J.G. Farrell's Troubles. I'm a little worried it'll get recalled before I get it read, but maybe no one else at the university is interested in the Lost Booker.

James Joyce's Ulysses. W. and I intend to have this finished by Labor Day. (I'm currently in the Circe chapter.)

Rebecca West's This Real Night. For my too-long-neglected Rebecca West project.

Wallace Stegner's The Big Rock Candy Mountain.

J.D. Hallman's The Hospital for Bad Poets.

Mary Lee Settle's Know Nothing.

Doris Lessing's The Sweetest Dream.

Doris Betts' The Scarlet Thread.

Maggie O'Farrell's The Hand that First Held Mine. Review copy.

Tom Rachman's The Imperfectionists.

Julie Orringer's The Invisible Bridge. My most recent purchase.

Justin Cronin's The Passage.

Wendy Moffat's A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E.M. Forster.

And my random question: Are there any extroverts who prefer character over plot in their reading? I know some introverts who prefer plot over character, but I can't come up with any extroverted acquaintances who prefer riding a character's thought waves over watching the character pick up the surfboard and head to the beach.

Tuesday, June 01, 2010

Lorna Sage's Bad Blood

A friend called me a few weeks back to talk about a memoir that she was reading. She liked it, but was having some issues with it at the same time. No one could recall memories from when they were five years old in such detail, she complained. And all that direct dialogue! Surely no one could remember the exact words spoken from that stage of their life. Had I believed all this when I read it?

And all I could muster was an Eh, it's all just a marketing decision now, whether a book is classified as fiction or a memoir. You just have to accept it as a story, appreciate the writing if you can, rather than getting yourself worked up over whether everything in the book actually happened. There's a lot of seepage these days.

Well, now that I've read Lorna Sage's Bad Blood, the 2001 Whitbread Prize-winning memoir, I get to eat my words. This is a clear-cut memoir, free of the fictiony trappings I've grown so accustomed to in the genre over the years.

Literary critic, author, and professor Lorna Sage, who did not allow a teenage pregnancy and early marriage to keep her from obtaining an education and embarking on a career as the norms of the times would have had it, traces her own "bad blood" to that of her maternal grandfather. A Welsh vicar with well-documented vices (he kept a diary of his affairs with which his wife periodically blackmailed him), he taught Lorna to read at the age of four and took her on his round of bars: "I was the perfect alibi, since neither my mother nor my grandmother had any idea that there were pubs so low and lawless that they would turn a blind eye to children." She saw herself as being on her grandfather's side so she never told on him.

Because the grandmother! Many women of her generation found themselves married to philandering men taken to drink. "What made their marriage more than a run-of-the-mill case of domestic estrangement was her refusal to accept her lot," Sage writes. "She stayed furious all the days of her life -- so sure of her ground, so successfully spoiled, that she was impervious to the social pressures and propaganda that made most women settle down to play the part of wife. Sex, genteel poverty, the responsibilities of motherhood, let alone the duties of the vicar's helpmeet, she refused any part of. They were in her view stinking offences, devilish male plots to degrade her. When he took to booze and other women (which he might well have done anyway, although she provided him with a kind of excuse by making the vicarage hearth so hostile) her loathing for him was perfected. He was the one who had conned her into leaving her real home, her girlhood, the shop where you never had to pay for anything, the endless tea party. It was as though he'd invented sex and pain and want and exposure. She turned patriarchal attitudes inside out: he was God to her. That is, he was making it up as he went along, to spite her and with no higher Authority to back him up."

Needless to say, being raised by such a brawling pair worked a number on Sage's mother. Used as a household drudge during the War years when she and the young Lorna lived with them in the filthy vicarage, she never managed to throw off her early influences: she couldn't cook, keep her modern council-house clean, "she had a kind of genius for travesty when it came to domestic science." Her husband willingly takes on the role of realist protector to her inept dreamer when he returns at the war's end and Sage observes: "in truth they were more than one flesh, they had formed and sustained each other, they had one story between them and it wasn't at all easy for me or my brother to inhabit it. I regularly cast myself in the part of the clever, unwanted child who's sent out to lose herself in the forest, but manages nonetheless to find her own way, being secretive, untruthful, disobedient, and so on and on, as they never ceased to complain. The children of violently unhappy marriages, like my mother, are often hamstrung for life, but the children of happier marriages have problems too -- all the worse, perhaps, because they don't have virtue on their side."

But the memoirs of those raised in happier marriages are often hamstrung as well. The most interesting characters in Bad Blood are certainly the grandparents, whose stories are told at the beginning. As the dysfunction dissipates in Sage's family, despite Sage's claims of virtuelessness, the lives of the characters become less compelling to read about. The story becomes more one of growing up at that particular time, in that particular environment. Sage and her husband may have broken the rules and gotten away with it, and their daughter may well have been the future, but the bad blood they're predisposed to seems to have been less influential than that of the changing environment. That's a loss for non-fictionalized memoir writing, but heartening news for reality.

Please feel free to join in the discussion of Bad Blood at Slaves of Golconda.

And all I could muster was an Eh, it's all just a marketing decision now, whether a book is classified as fiction or a memoir. You just have to accept it as a story, appreciate the writing if you can, rather than getting yourself worked up over whether everything in the book actually happened. There's a lot of seepage these days.

Well, now that I've read Lorna Sage's Bad Blood, the 2001 Whitbread Prize-winning memoir, I get to eat my words. This is a clear-cut memoir, free of the fictiony trappings I've grown so accustomed to in the genre over the years.

Literary critic, author, and professor Lorna Sage, who did not allow a teenage pregnancy and early marriage to keep her from obtaining an education and embarking on a career as the norms of the times would have had it, traces her own "bad blood" to that of her maternal grandfather. A Welsh vicar with well-documented vices (he kept a diary of his affairs with which his wife periodically blackmailed him), he taught Lorna to read at the age of four and took her on his round of bars: "I was the perfect alibi, since neither my mother nor my grandmother had any idea that there were pubs so low and lawless that they would turn a blind eye to children." She saw herself as being on her grandfather's side so she never told on him.

Because the grandmother! Many women of her generation found themselves married to philandering men taken to drink. "What made their marriage more than a run-of-the-mill case of domestic estrangement was her refusal to accept her lot," Sage writes. "She stayed furious all the days of her life -- so sure of her ground, so successfully spoiled, that she was impervious to the social pressures and propaganda that made most women settle down to play the part of wife. Sex, genteel poverty, the responsibilities of motherhood, let alone the duties of the vicar's helpmeet, she refused any part of. They were in her view stinking offences, devilish male plots to degrade her. When he took to booze and other women (which he might well have done anyway, although she provided him with a kind of excuse by making the vicarage hearth so hostile) her loathing for him was perfected. He was the one who had conned her into leaving her real home, her girlhood, the shop where you never had to pay for anything, the endless tea party. It was as though he'd invented sex and pain and want and exposure. She turned patriarchal attitudes inside out: he was God to her. That is, he was making it up as he went along, to spite her and with no higher Authority to back him up."

Needless to say, being raised by such a brawling pair worked a number on Sage's mother. Used as a household drudge during the War years when she and the young Lorna lived with them in the filthy vicarage, she never managed to throw off her early influences: she couldn't cook, keep her modern council-house clean, "she had a kind of genius for travesty when it came to domestic science." Her husband willingly takes on the role of realist protector to her inept dreamer when he returns at the war's end and Sage observes: "in truth they were more than one flesh, they had formed and sustained each other, they had one story between them and it wasn't at all easy for me or my brother to inhabit it. I regularly cast myself in the part of the clever, unwanted child who's sent out to lose herself in the forest, but manages nonetheless to find her own way, being secretive, untruthful, disobedient, and so on and on, as they never ceased to complain. The children of violently unhappy marriages, like my mother, are often hamstrung for life, but the children of happier marriages have problems too -- all the worse, perhaps, because they don't have virtue on their side."

But the memoirs of those raised in happier marriages are often hamstrung as well. The most interesting characters in Bad Blood are certainly the grandparents, whose stories are told at the beginning. As the dysfunction dissipates in Sage's family, despite Sage's claims of virtuelessness, the lives of the characters become less compelling to read about. The story becomes more one of growing up at that particular time, in that particular environment. Sage and her husband may have broken the rules and gotten away with it, and their daughter may well have been the future, but the bad blood they're predisposed to seems to have been less influential than that of the changing environment. That's a loss for non-fictionalized memoir writing, but heartening news for reality.

Please feel free to join in the discussion of Bad Blood at Slaves of Golconda.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

A bang, not a whimper

Two months into L.'s retirement, and I'm finished with the stockpiling of books. No more book purchases! Or at least, no purcha...

-

(See also Musee des Beaux Arts ) As far as mental anguish goes, the old painters were no fools. They understood how the mind, the freakiest ...

-

Lou wondered where his information would go when he died. Would filaments of learning plant patterns on earth? Would his brain train the sin...