Prattling not too intelligently about India and elephants and Nabobs' jewels, she fiddled about her garden cutting lavender-flowers till the basket she had slung on her forearm was full, and then fluttered indoors to put them on her windowsills to dry; and then she sat behind her silver equipage and gave him very good home-made scones and country butter, and giggled a great deal. Looking on the suavity of her face and the meek pliancy of her form and manners, which were such that if one found her in one's way one might surely pick her up and loop her round a hook on the door without encountering physical or mental resistance, he said to himself, "It must be that the other night my intellects were disordered. Certainly there is as little sinister in my Harriet here as there is in drinking sugared tea out of a pretty cup. She could not read my thoughts. I doubt if she could read her primer." But something tender in him, that same part which had before the mirror designed to buy her a little ring for her little hand, rebuked him. "Whatever happened last night, whether it was magic or the dropping of an ill-considered word, you betrayed to her that no woman is as much to you as the prospect of rising in the world, and you betrayed it in an ugly hour, and in a roughish shape. Decidedly you have brought no good fortune to the girl. For only yesterday she was as kind to you as may be, and to-day you tell her you must immediately sail for the Indies. You cannot say that you have treated her handsomely." At that he could not help but fall a-moping.

Just then Harriet, smiling like a doll, raised her hand to her head and withdrew the sole pin that held in place her Grecian knot; and the sleek serpents of her hair slipped down over her shoulders and covered her bosom, their curled heads lying in her lap. In but one neat, fluent movement she again compressed its fineness and impaled it; but not before he had called himself a fool for thinking that the loss of a lover could mean much to any creature so rich in all the most seductive attributes of her sex. With an easy conscience, therefore, he rose to his feet and bade her good-bye; and remained in a state of cheerfulness until, when he was re-entering his flat in the Temple, his hand left the latch-key sticking in the lock while his chin sank on his breast and he stood staring very stupidly at the door. It had occurred to him that if she had read his compunction for leaving her so soon and so abruptly she could not have devised a prettier and kinder way of relieving his mind. Yet of that action, though it drearily assumed in his mind an air of complete probability, he thought not as one usually thinks of pretty and kind things. When, once across his threshold, he vehemently slammed the door, the vehemence was because he imagined himself slamming it on the prodigiousness of Harriet Hume.

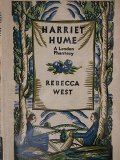

--Rebecca West

No comments:

Post a Comment