As we grow older and see the ends of stories as well as their beginnings, we realize that to the people who take part in them it is almost of greater importance that they should be stories, that they should form a recognizable pattern, than that they should be happy or tragic. The men and women who are withered by their fates, who go down to death reluctantly but without noticeable regrets for life, are not those who have lost their mates prematurely or by perfidy, or who have lost battles or fallen from early promise in circumstances of public shame, but those who have been jilted or were the victims of impotent lovers, who have never been summoned to command or been given any opportunity for success or failure. Art is not a plaything, but a necessity, and its essence, form, is not a decorative adjustment, but a cup into which life can be poured and lifted to the lips and be tasted. If one's own existence has no form, if its events do not come handily to mind and disclose their significance, we feel about ourselves as if we were reading a bad book. We can all of us judge the truth of this, for hardly any of us manage to avoid some periods when the main theme of our lives is obscured by details, when we involve ourselves with persons who are insufficiently characterized; and it is possibly true not only of individuals, but of nations. What would England be like if it had not its immense Valhalla of kings and heroes, if it had not its Elizabethan and its Victorian ages, its thousands of incidents which come up in the mind, simple as icons and as miraculous in their suggestion that what England has been it can be again, now and for ever? What would the United States be like if it had not those reservoirs of triumphant will-power, the historical facts of the War of Independence, of the giant American statesmen, and of the pioneering progress into the West, which every American citizen has at his mental command and into which he can plunge for revivification at any minute? To have a difficult history makes, perhaps, a people who are bound to be difficult in any conditions, lacking these means of refreshment.

--Rebecca West, discussing Croatian history in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon

Sunday, July 31, 2005

Like trying to plant cut flowers

And just when I become interested in Thomas Paine, along comes Harvey J. Kaye's Thomas Paine and the Promise of America. From Joseph Ellis' review in the Sunday Book Review:

"Though a self-confessed partisan, Kaye provides the most comprehensive assessment yet of Paine's controversial reputation, and the results congeal into three categories: first, the Paine haters, like Theodore Roosevelt, who called him a 'filthy little atheist' because of The Age of Reason (1794-95), a frontal assault on Christianity; second, prominent American statesmen and authors like Abraham Lincoln, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, who quoted selectively from Paine but only to serve their own political purposes; third, the longer list of radicals, a kind of roll call of the American left, who drew inspiration from Paine's uncompromising convictions. A selection from the last, in rough chronological order, includes Robert Owen, William Lloyd Garrison, Victoria Woodhull, Henry George, Eugene Debs, Clarence Darrow, Henry Wallace, Saul Alinsky, C. Wright Mills, Tom Hayden and Bob Dylan.

"Oddly enough, however, over the past 30 years Paine's chief fans have appeared within the conservative wing of the Republican Party, making Paine, like Jefferson, the proverbial man for all seasons. Though weird, and surely not the legacy Kaye has in mind, the Goldwater-Reagan-Gingrich persuasion has a plausible claim on the libertarian side of the Paine legacy, which is deeply suspicious of all forms of consolidated political power and views government as ''them'' rather than 'us.' Paul Wolfowitz would also be able to cite Paine in support of George W. Bush's Iraq policy, since Paine believed that democratic values were both universal and self-enacting. History makes strange bedfellows.

"Which is to say that 'the promise of America' that Paine glimpsed so lyrically at the start cannot be easily translated into our 21st-century idiom without distorting the intellectual integrity of its 18th-century origins. Paine, like Jefferson, was a product of the Enlightenment who sincerely believed there was a natural order of perfect freedom and equality that had been hijacked by medieval kings and priests. If only, as Diderot put it, the last king could be strangled with the entrails of the last priest, the natural order would be restored, naturally. Marx's later formulation of the same illusion was that the state would wither away, leaving a harmonious and classless society. In the wake of Darwin's depiction of nature, Freud's depiction of human nature, the senseless slaughter of World War I and the genocidal tragedies of the 20th century, Paine's optimistic assumptions appear naïve in the extreme.

"What a reincarnated Paine would say about our altered political and intellectual landscape is impossible to know. Kaye hears his voice more clearly and unambiguously than I do, a clarity of conviction that I envy. My more muddled position is that bringing Paine's words and ideas into our world is like trying to plant cut flowers."

"Though a self-confessed partisan, Kaye provides the most comprehensive assessment yet of Paine's controversial reputation, and the results congeal into three categories: first, the Paine haters, like Theodore Roosevelt, who called him a 'filthy little atheist' because of The Age of Reason (1794-95), a frontal assault on Christianity; second, prominent American statesmen and authors like Abraham Lincoln, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, who quoted selectively from Paine but only to serve their own political purposes; third, the longer list of radicals, a kind of roll call of the American left, who drew inspiration from Paine's uncompromising convictions. A selection from the last, in rough chronological order, includes Robert Owen, William Lloyd Garrison, Victoria Woodhull, Henry George, Eugene Debs, Clarence Darrow, Henry Wallace, Saul Alinsky, C. Wright Mills, Tom Hayden and Bob Dylan.

"Oddly enough, however, over the past 30 years Paine's chief fans have appeared within the conservative wing of the Republican Party, making Paine, like Jefferson, the proverbial man for all seasons. Though weird, and surely not the legacy Kaye has in mind, the Goldwater-Reagan-Gingrich persuasion has a plausible claim on the libertarian side of the Paine legacy, which is deeply suspicious of all forms of consolidated political power and views government as ''them'' rather than 'us.' Paul Wolfowitz would also be able to cite Paine in support of George W. Bush's Iraq policy, since Paine believed that democratic values were both universal and self-enacting. History makes strange bedfellows.

"Which is to say that 'the promise of America' that Paine glimpsed so lyrically at the start cannot be easily translated into our 21st-century idiom without distorting the intellectual integrity of its 18th-century origins. Paine, like Jefferson, was a product of the Enlightenment who sincerely believed there was a natural order of perfect freedom and equality that had been hijacked by medieval kings and priests. If only, as Diderot put it, the last king could be strangled with the entrails of the last priest, the natural order would be restored, naturally. Marx's later formulation of the same illusion was that the state would wither away, leaving a harmonious and classless society. In the wake of Darwin's depiction of nature, Freud's depiction of human nature, the senseless slaughter of World War I and the genocidal tragedies of the 20th century, Paine's optimistic assumptions appear naïve in the extreme.

"What a reincarnated Paine would say about our altered political and intellectual landscape is impossible to know. Kaye hears his voice more clearly and unambiguously than I do, a clarity of conviction that I envy. My more muddled position is that bringing Paine's words and ideas into our world is like trying to plant cut flowers."

Friday, July 29, 2005

The idea yesterday was to read a hefty chunk of Emerson Among the Eccentrics. I want to finish Part Two, the section on the 1840s, before I read Emerson's essays from that decade: "History," "Self-Reliance," "The Over-Soul," etc.

I read "Waldo Minor," the chapter on the death of Emerson's five-year-old son and the months of mourning that follow--Emerson's emotional numbness, Lidian's overwhelming grief, adopted family member Thoreau suffering also from the loss of his brother to lockjaw, and how Margaret Fuller comes to spend 40 days with the family and makes Lidian feel even more desolate than before. Emerson appears to have done nothing to ease Lidian's jealousy and puts Fuller off at the same time he's telling her the "soul knows nothing of marriage, in the sense of a permanent union between two personal existences. The soul is married to each new thought as it enters into it." (Okay, I do wish Jon Stewart had quoted a little Emerson to Rick Santorum the other night but how inappropriate for Emerson to be going on about this at such a time.)

How could I go on to the next chapter on an entirely new character, Theodore Parker? I read the new Serenity comic book (eh), I read "Threnody," I checked the index in Susan Jacoby's Freethinkers for any references to Emerson (he blurbed Leaves of Grass. Robert Ingersoll (who?) delivered Whitman's eulogy. Both Ingersoll and Whitman's father were great admirers of Revolutionary pamphleteer Thomas Paine). I settled down with Emerson's 1855 essay "Woman" because I can't get out of my mind the absence of appreciation in Emerson for his two little daughters, Ellen and Edith, who is just a couple months old at the time of Waldo's death, in "Waldo Minor," and I don't know if that is Baker's lack of interest in the girls or his own (Waldo was "the far shining stone that made home glitter to me when I was farthest absent. . .Yet the other children may be good babes yet—I will breathe no despair on their sweet fortunes. Nelly is a good little housewife and that Lidianetta may come to great heart and honor in the months and years to come." Ugh, ugh, ugh).

"Woman" leaves me feeling most conflicted. Yes, he is progressive enough to believe women should have the right to vote, he does say, "Let the laws be purged of every barbarous remainder, every barbarous impediment to women. Let the public donations for education be equally shared by them, let them enter a school as freely as a church, let them have and hold and give their property as men do theirs." But he is also awfully patronizing in his views of "the best women," "the truest women," and I decide I've had my fill of Emerson for the day.

At the library I gather the collected works of Thomas Paine and the miscellaneous works from the 12-volume set of Robert Ingersoll. I read portions of "Common Sense" and the story of Paine's life as outlined in the introduction. I turn to the hodgepodge of views covered in Ingersoll, I read a couple websites of Ingersoll quotes and an anti-Ingersoll site that concludes that Ingersoll the man (not his ideas) is worthy of no respect, and I read from Ingersoll's essay on Paine and the attacks and slanders leveled against him, and then I read this: "Theodore Parker attacked the Old Testament and Calvinistic theology with the same weapons and with a bitterness excelled by no man who has expressed his thoughts in our language."

So today I'm back to Emerson Among the Eccentrics and the chapter on Theodore Parker.

I read "Waldo Minor," the chapter on the death of Emerson's five-year-old son and the months of mourning that follow--Emerson's emotional numbness, Lidian's overwhelming grief, adopted family member Thoreau suffering also from the loss of his brother to lockjaw, and how Margaret Fuller comes to spend 40 days with the family and makes Lidian feel even more desolate than before. Emerson appears to have done nothing to ease Lidian's jealousy and puts Fuller off at the same time he's telling her the "soul knows nothing of marriage, in the sense of a permanent union between two personal existences. The soul is married to each new thought as it enters into it." (Okay, I do wish Jon Stewart had quoted a little Emerson to Rick Santorum the other night but how inappropriate for Emerson to be going on about this at such a time.)

How could I go on to the next chapter on an entirely new character, Theodore Parker? I read the new Serenity comic book (eh), I read "Threnody," I checked the index in Susan Jacoby's Freethinkers for any references to Emerson (he blurbed Leaves of Grass. Robert Ingersoll (who?) delivered Whitman's eulogy. Both Ingersoll and Whitman's father were great admirers of Revolutionary pamphleteer Thomas Paine). I settled down with Emerson's 1855 essay "Woman" because I can't get out of my mind the absence of appreciation in Emerson for his two little daughters, Ellen and Edith, who is just a couple months old at the time of Waldo's death, in "Waldo Minor," and I don't know if that is Baker's lack of interest in the girls or his own (Waldo was "the far shining stone that made home glitter to me when I was farthest absent. . .Yet the other children may be good babes yet—I will breathe no despair on their sweet fortunes. Nelly is a good little housewife and that Lidianetta may come to great heart and honor in the months and years to come." Ugh, ugh, ugh).

"Woman" leaves me feeling most conflicted. Yes, he is progressive enough to believe women should have the right to vote, he does say, "Let the laws be purged of every barbarous remainder, every barbarous impediment to women. Let the public donations for education be equally shared by them, let them enter a school as freely as a church, let them have and hold and give their property as men do theirs." But he is also awfully patronizing in his views of "the best women," "the truest women," and I decide I've had my fill of Emerson for the day.

At the library I gather the collected works of Thomas Paine and the miscellaneous works from the 12-volume set of Robert Ingersoll. I read portions of "Common Sense" and the story of Paine's life as outlined in the introduction. I turn to the hodgepodge of views covered in Ingersoll, I read a couple websites of Ingersoll quotes and an anti-Ingersoll site that concludes that Ingersoll the man (not his ideas) is worthy of no respect, and I read from Ingersoll's essay on Paine and the attacks and slanders leveled against him, and then I read this: "Theodore Parker attacked the Old Testament and Calvinistic theology with the same weapons and with a bitterness excelled by no man who has expressed his thoughts in our language."

So today I'm back to Emerson Among the Eccentrics and the chapter on Theodore Parker.

Wednesday, July 27, 2005

I don't like people summing up books for me. Tempt me with a title, a scene, a quotation, yes, but not with the whole story. Fellow enthusiasts, jacket blurbs, teachers and histories of literature destroy much of our reading pleasure by ratting on the plot. And as one grows older, memory, too, can spoil much of the pleasure of being ignorant of what will happen next. I can barely recall what it was like not to know that Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were one and the same person, or that Crusoe would meet his man Friday.

--Alberto Manguel, A Reading Diary

--Alberto Manguel, A Reading Diary

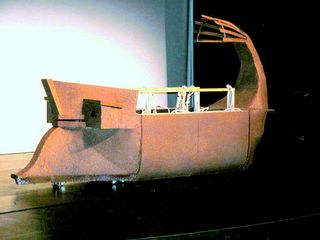

S. was in a production of The Odyssey last week, and this is the boat the kids built prior to the performance.

And here are Jack Aubrey's views towards Ulysses and those who wish to go off course to catch a glimpse of Ithaca, as told in a letter Stephen Maturin writes home to Diana in Treason's Harbour:

. . . 'To Ithaca itself, upon my word of honour. But would any amount of pleading on my part or on the part of all the literate members of the ship's company induce that animal to bear away for the sacred spot? It would not. Certainly he had heard of Homer, and had indeed looked into Mr Pope's version of his tale; but for aught he could make out, the fellow was no seaman. Admittedly Ulysses had no chronometer, and probably no extant neither; but with no more than log, lead and lookout an officer-like commander would have found his way home from Troy a d-d sight quicker than that. Hanging about in port and philandering, that was what it amounted to, the vice of navies from the time of Noah to that of Nelson. And as for that tale of all his foremast hands being turned into swine, so that he could not win his anchor or make sail, why, he might tell that to the Marines. Besides, he behaved like a very mere scrib to Queen Dido-though on second thought perhaps that was the other cove, the pious Anchises. But it was all one: they were six of one and half a dozen of the other, neither seamen nor gentlemen, and both of 'em God d-d bores into the bargain. For his part he far preferred what Mowett and Rowan wrote; that was poetry a man could get his teeth into, and it was sound seamanship too; in any case he was here to conduct his convoy into Santa Maura, not to gape at curiosities.'

Tuesday, July 26, 2005

Tuesday morning, Jillian from Disasters calls. Apparently an airman named Loolerton has poisoned a shitload of beavers. I say we don’t kill beavers, we harvest them, because otherwise they nibble through our Pollution Control Devices (P.C.D.s) and polluted water flows out of our Retention Area and into the Eisenhower Memorial Wetland, killing beavers.

“That makes sense,” Jillian says, and hangs up.

The press has a field day. “AIR FORCE KILLS BEAVERS TO SAVE BEAVERS,” says one headline. “MURDERED BEAVERS SPEAK OF AIR FORCE CRUELTY,” says another.

“We may want to PIDS this,” Mr. Rimney says.

--George Saunders, "CommComm"

What a strange, incredibly fine story. Go read it now. Why haven't I been reading George Saunders these past few years?

“That makes sense,” Jillian says, and hangs up.

The press has a field day. “AIR FORCE KILLS BEAVERS TO SAVE BEAVERS,” says one headline. “MURDERED BEAVERS SPEAK OF AIR FORCE CRUELTY,” says another.

“We may want to PIDS this,” Mr. Rimney says.

--George Saunders, "CommComm"

What a strange, incredibly fine story. Go read it now. Why haven't I been reading George Saunders these past few years?

Monday, July 25, 2005

Reading update

Listened to 11 pages or so of Treason's Harbour while on the treadmill this morning before admitting defeat. Beyond the fact that Jack lost the chelengk from his hat in the sand and that Stephen and Martin were having a grand old time with the diving bell, I could not follow anything that was happening and had to reread those pages at lunch. Books with simple sentence structures to exercise to from now on. I'll read, not listen, to the rest of this one.

So glad I sent for an ILL copy of E.C. Spykman's The Wild Angel. From Sarah L. Rueter's introduction:

I also learned that Spykman's travels included "taking a cargo ship to Samoa by way of the peaks of Darien, Pitcairn Island, and New Zealand, and making a pilgrimage to the grave of Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa." One day if I find myself with microfilm access to the Atlantic Monthly (1923-1927) I can read her articles. Her husband Nicholas Spykman was no mere teacher, as I'd assumed, but the founder of the Department of International Relations at Yale.

Desperately trying to catch up in Don Quixote this week. I'm about 20 chapters behind schedule.

Finished Half-Blood Prince yesterday morning and immediately began to read all the discussions I'd assiduously shied away from. All I have to say here is that what most seem to be hoping for in the final book involving a character that everyone sees differently from the way he's written, from the way Rowling has described him in interviews, what everyone seems to be expecting—well, it would certainly make a lot of readers blissfully happy, but in the process wouldn't it undermine Rowling's philosophical and moral underpinnings? It wouldn't be a redemption of a character, it would merely be a shift in readers' perspectives (or an underscoring of what many already believe anyway), and it would serve to promote the notion that the ends justify the means. I can't accept that's Rowling's intent.

So glad I sent for an ILL copy of E.C. Spykman's The Wild Angel. From Sarah L. Rueter's introduction:

E.C. Spykman knew her characters, the settings, and the situation of which she

wrote with an intimacy that came from having lived them herself. Born Elizabeth

Choate in Southboro, Massachusetts in 1896, she was one of six children—four

boys and two girls of a prominent Boston lawyer in a family that had been

vigorous and accomplished for generations. She grew up in the midst of a lush

countryside of vast lawns, gardens, and pastures which belonged largely to her

own extensive family and which developed in her a sense of freedom, a spirit of

belonging, and a strong awareness of nature which pervades all of her writing.

Later she was sent to Boston to be socialized, and to the Westover School in

Connecticut to be educated, but it is the influence of those early years in

Southboro which are at the heart of her novels.

All that happens in her stories really did happen, but not always to her. She never made anything up, yet the books cannot strictly be called biographical, because with consummate skill she transformed, rearranged, borrowed in time, exaggerated, and subdued until the whole became a kaleidoscope rather than a mirror of her childhood. One can say that Jane Cares is very much like E.C. Spkyman herself; that the incorrigible Edie is a composite of her younger sister Josie and of her sister's

daughter Josie (the two Josies to whom The Wild Angel is dedicated); that Ted is

like her two oldest brothers and Hubert like her two youngest brothers; that

Summerton is Southboro, that Charlottesville is Boston and that the Cape Cod

locale of the third book is Woods Hole. But, while it can be fascinating to

explore origins, it is the power of her writing that gives E.C. Spykman's

stories their authenticity. Her sharp and honest portrayals of character, her

understanding of the perceptions and emotions of children, her natural dialogue

and sensitive evocation of place and time are what give her writing its truth.

I also learned that Spykman's travels included "taking a cargo ship to Samoa by way of the peaks of Darien, Pitcairn Island, and New Zealand, and making a pilgrimage to the grave of Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa." One day if I find myself with microfilm access to the Atlantic Monthly (1923-1927) I can read her articles. Her husband Nicholas Spykman was no mere teacher, as I'd assumed, but the founder of the Department of International Relations at Yale.

Desperately trying to catch up in Don Quixote this week. I'm about 20 chapters behind schedule.

Finished Half-Blood Prince yesterday morning and immediately began to read all the discussions I'd assiduously shied away from. All I have to say here is that what most seem to be hoping for in the final book involving a character that everyone sees differently from the way he's written, from the way Rowling has described him in interviews, what everyone seems to be expecting—well, it would certainly make a lot of readers blissfully happy, but in the process wouldn't it undermine Rowling's philosophical and moral underpinnings? It wouldn't be a redemption of a character, it would merely be a shift in readers' perspectives (or an underscoring of what many already believe anyway), and it would serve to promote the notion that the ends justify the means. I can't accept that's Rowling's intent.

“Go and get him Saddam's gun,” Condi said. “You know how he likes to hold it.”

The William Faulkner parody (The Administration and the Fury) that made me laugh until I cried last February has won the Faux Faulkner contest; Ernest Hemingway parody winners have also been chosen.

A Guardian article on Elizabeth Kostova and The Historian. I loaned my copy last week to my mother-in-law, who'd gone to the terrible horrible bookstore in our hometown and asked for "the new vampire novel" that was so popular this summer. Terrible horrible bookstore didn't have a clue what she was talking about.

The list of teen authors stretches back to 19-year-old Mary Shelley and Frankenstein; The CSM touches upon a few of these youngsters in its article on Helen Oyeyemi and The Icarus Girl.

A Guardian article on Elizabeth Kostova and The Historian. I loaned my copy last week to my mother-in-law, who'd gone to the terrible horrible bookstore in our hometown and asked for "the new vampire novel" that was so popular this summer. Terrible horrible bookstore didn't have a clue what she was talking about.

The list of teen authors stretches back to 19-year-old Mary Shelley and Frankenstein; The CSM touches upon a few of these youngsters in its article on Helen Oyeyemi and The Icarus Girl.

Sunday, July 24, 2005

Claudie's "listening intently" expression during this weekend's cd ripping marathon. Now playing: Wayne Hancock.

Don't forget to check out The Ark on Fridays and the Carnival of the Cats on Sundays for a round up of the best and latest pet blogging photos. This week's Carnival is being hosted by Oubliette.

Friday, July 22, 2005

Donkey Oat-E

What makes Southern literature so distinctive? Is it the setting, the writer's sensibility, the concern with the grotesque? Jerry Leath Mills speculates "there is indeed a single, simple, litmus-like test for the quality of Southernness in literature. . . . The test is: Is there a dead mule in it?"

Don't forget to check out The Ark

Thursday, July 21, 2005

Lorrie Moore

Via a Bookslut link to a new interview with Lorrie Moore, I learned she'd been named 2005 winner of the PEN/Malamud Award for short fiction. How'd I miss that bit of news? It evidently happened last month midway between S.'s foot surgery and R.'s departure for Germany. Ah well: distractions.

Searching for more on Moore today, I found this 1998 Q&A, a 1998 profile in Ploughshares, and a Cup of Chicha '04 transcript of a Q&A between Moore and 40 MFA students--scroll down for a look at the Lorrie Moore T-shirts. I would wear one of those.

Searching for more on Moore today, I found this 1998 Q&A, a 1998 profile in Ploughshares, and a Cup of Chicha '04 transcript of a Q&A between Moore and 40 MFA students--scroll down for a look at the Lorrie Moore T-shirts. I would wear one of those.

Now he would never write the things that he had saved to write until he knew enough to write them well. Well, he would not have to fail at trying to write them either. Maybe you could never write them, and that was why you put them off and delayed the starting. Well he would never know, now.

You kept from thinking and it was all marvellous. You were equipped with good insides so that you did not go to pieces that way, the way most of them had, and you made an attitude that you cared nothing for the work you used to do, now that you could no longer do it. But, in yourself, you said that you would write about these people; about the very rich; that you were really not of them but a spy in their country; that you would leave it and write of it and for once it would be written by some one who knew what he was writing of. But he would never do it, because each day of not writing, of comfort, of being that which he despised, dulled his ability and softened his will to work so that, finally, he did no work at all. The people he knew now were all much more comfortable when he did not work.

There wasn't time, of course, although it seemed as though it telescoped so that you might put it all into one paragraph if you could get it right.

Ernest Hemingway was born on this date in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1899.

You kept from thinking and it was all marvellous. You were equipped with good insides so that you did not go to pieces that way, the way most of them had, and you made an attitude that you cared nothing for the work you used to do, now that you could no longer do it. But, in yourself, you said that you would write about these people; about the very rich; that you were really not of them but a spy in their country; that you would leave it and write of it and for once it would be written by some one who knew what he was writing of. But he would never do it, because each day of not writing, of comfort, of being that which he despised, dulled his ability and softened his will to work so that, finally, he did no work at all. The people he knew now were all much more comfortable when he did not work.

There wasn't time, of course, although it seemed as though it telescoped so that you might put it all into one paragraph if you could get it right.

Ernest Hemingway was born on this date in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1899.

Wednesday, July 20, 2005

From the Chronicle of Higher Education:

What does it mean when the University of Texas at

Austin removes nearly all of the books from its undergraduate library to

make room for coffee bars, computer terminals, and lounge chairs? What are

students in those "learning commons" being taught that is qualitatively better

than what they learned in traditional libraries?

I think the absence of books confirms the disposition to regard them as

irrelevant. Many entering students come from nearly book-free homes. Many have

not read a single book all the way through; they are instead trained to surf and

skim. Teachers increasingly find it difficult to get students to consult printed

materials, and yet we are making those materials even harder to obtain. Online

journal articles are suitable for searching and extraction, but how conducive is

a computer for reading a novel?

Alison was a Sensitive: which is to say, her senses were arranged in a different way from the senses of most people. She was a medium: dead people talked to her, and she talked back. She was a clairvoyant; she could see straight through the living, to their ambitions and secret sorrows, and tell you what they kept in their bedside drawers and how they had travelled to the venue. She wasn't (by nature) a fortune-teller, but it was hard to make people understand that. Prediction, though she protested against it, had become a lucrative part of her business. At the end of the day, she believed, you have to suit the public and give them what they think they want. For fortunes, the biggest part of the trade was young girls. They always thought there might be a stranger on the horizon, love around the corner. They hoped for a better boyfriend than the one they'd got--more socialized, less spotty: or at least one who wasn't on remand. Men, on their own behalf, were not interested in fortune or fate. They believed they made their own, thanks very much. As for the dead, why should they worry about them? If they need to talk to their relatives, they have women to do that for them.

--Hilary Mantel, Beyond Black

--Hilary Mantel, Beyond Black

Tuesday, July 19, 2005

Be still my heart! The new Harry Potter made its way from the UK and into my mailbox in record time.

Now for the dilemma: do I give it to its rightful owner and wait my turn or do I take it to work tonight and read it posthaste, not even mentioning it to S. until after I'm finished? I know, I know, but he's in a play on Friday and ought to devote every single moment of his existence between now and then to memorizing and practicing his lines, don't you think? I mean really. What if Harry Potter takes over his brain and there's no room for Homer any more?

Or, I could start it now, give it to him to read while I'm at work, then resume reading once he's gone to bed.

Or, I could state out right to him, "I'm reading it first because you told me who died in the last one and have forfeited any right to ever again read a Harry Potter book first."

Or I could snag the latest Hilary Mantel off the shelf when I go to work tonight and put myself above the fray--there's a wonderful article about it--and Mantel-- here.

Now for the dilemma: do I give it to its rightful owner and wait my turn or do I take it to work tonight and read it posthaste, not even mentioning it to S. until after I'm finished? I know, I know, but he's in a play on Friday and ought to devote every single moment of his existence between now and then to memorizing and practicing his lines, don't you think? I mean really. What if Harry Potter takes over his brain and there's no room for Homer any more?

Or, I could start it now, give it to him to read while I'm at work, then resume reading once he's gone to bed.

Or, I could state out right to him, "I'm reading it first because you told me who died in the last one and have forfeited any right to ever again read a Harry Potter book first."

Or I could snag the latest Hilary Mantel off the shelf when I go to work tonight and put myself above the fray--there's a wonderful article about it--and Mantel-- here.

I don't have the concentration to read books these days.

Here's a press conference with J.K. Rowling.

An article that discusses the losses and the gains in the new curriculum.

And via Jeannette, an article on introducing children to art, film and literature.

Here's a press conference with J.K. Rowling.

An article that discusses the losses and the gains in the new curriculum.

And via Jeannette, an article on introducing children to art, film and literature.

Monday, July 18, 2005

Monday morning links

Neo-con authors:

Great First Lines in Novels:

Yet, despite the disdain of the literati and his own linguisticAs I Lay Reading:

difficulties, Bush presides over an administration chock full of novelists,

particularly among the neo-conservative faction surrounding vice-president Dick

Cheney. Lynne Cheney, the vice-president’s wife, has written three novels, as

well as several children’s books. Before becoming the vice-president’s chief of

staff, Lewis Libby made his literary debut with a historical romance set in

early twentieth-century Japan. And, Richard Perle, who has been a formidable

advocate for an aggressive foreign policy as the erstwhile chairman of the

Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board (DPB), is the author of a Cold War thriller. At

the DPB, Perle shares the table with Newt Gingrich, who also has a thriller to

his credit, an alternative history novel set during World War II. When the Bush

administration sought the Pope’s blessing for the Iraq war, they sent over a

special diplomatic delegation to the Vatican headed by Michael Novak, a prolific

Catholic political philosopher and author of two autobiographical novels about

his religious experiences.

The presence of so many novelists in the corridors of power raises all

sorts of questions. For starters, is there some hidden link between a powerful

imagination and real-world power politics? And, what do these novels tell us

about how political decision-makers really see the world? (Jeet Heer)

This refusal to look away from pain is both what joins Faulkner and Oprah,

and what most strikingly divides them. In Faulkner the world is gone wrong, and

everything in it is hopelessly broken, whereas Oprah, who is similarly bold in

confronting the cruelties of the past, offers the mild remedy of "inspiration,"

a perpetual procession of heartwarming or heartbreaking personal stories of

overcoming fear. Her show is not likely to shift to a Faulknerian perspective on

the unmasterable past anytime soon. But she has gone beyond the intellectual

limits of the acceptably middlebrow--and of her own show--in openly embracing a

writer who is not only highly experimental in his prose but utterly despairing

in outlook. And that is little short of astonishing. (J. M.

Tyree)

Great First Lines in Novels:

Charlie Harris, professor emeritus of English at Illinois State University,

contemporary literature reader/critic extraordinaire (secretary of the Center for Book Culture.org and former director of the Unit for Contemporary Literature),

and all-around fine fellow, informs me that a bunch of literary-minded folk are

putting together a list of Great First Lines in Novels, as an arbitrary-but-fun

counterpart to the American Film Institute’s 100 great movie lines. (Michael

Berube)

Sunday, July 17, 2005

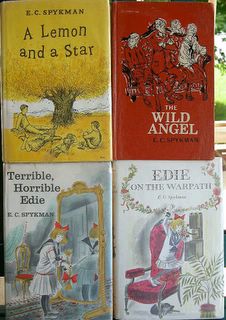

Celebrating E.C. Spykman

While the rest of the world devoted itself to reading and celebrating the latest Harry Potter (not that I'm too snooty to read it, it's just we're partial to the UK versions and ours won't be delivered for another week to 10 days), I spent my free time over the last few days with my favorite children's novels in honor of their author's birthday.

Elizabeth Choate was born in Southboro, Massachusetts, on this date in 1896. In her mid-thirties she married an educator, Nicholas Spykman (pronounced Speakman), and had two daughters. Her husband died in 1943. She contributed articles to Atlantic Monthly and wrote a history of the first 50 years of the Westover school for girls in Middlebury, Connecticut.

She published her first children's novel, A Lemon and a Star, in 1955. Two years later she published a sequel, The Wild Angel, which was followed in 1960 with the third installment in the continuing saga of the Cares children of Summerton, Massachusetts, Terrible, Horrible Edie. She died in 1965, and her fourth novel, Edie on the Warpath, was published the following year.

That's it-the sum total that I know about the woman who wrote the books that meant the most to me while I was growing up. I have no way of knowing if Jane Cares, whose tenth birthday on June 17, 1907, is recounted in the first chapter of A Lemon and a Star, is based on Elizabeth Choate's young self or if she was, in fact, more like younger sibling Edith, who shares her initials and whose adventures were worthy of two separate volumes, or some combination of the two. Who knows-they-along with brothers Theodore and Hubert--may be whole cloth inventions with no real life counterparts, although the back flap of one of the books claims they all stem from the author's childhood. Perhaps I can get more info by reading Sarah L. Rueter's introduction to The Wild Angel, which was republished by Gregg Press in 1981 (why only the second volume of the series?); I need to place an ILL request very soon.

The Cares themselves grew up in a large house in the country surrounded by dairy farms owned by various aunts and uncles, woods, open fields, swamps, and "reservoir basins that ran in a chain like a quiet river right through town, the family lawns and pastures along their borders." Their father took a train to work each day; "Edie had killed their real mother, as everybody knew, by having to get herself born," leaving the children at home with a house full of servants unable to keep them under control and out of trouble. When the four gain a stepmother near the end of A Lemon and a Star she manages to take the edge off the father's disciplinary excesses but Theodore, Jane, Hubert and Edie continue to run amuck (I first heard the phrase "run amuck" in these books as well as the word "lollapalooza"), having one exciting adventure after another: unauthorized steeplechases, walks across the top of the reservoir, encounters with country thugs and French governesses and foxes and skunks.

By the time Edie takes center stage in the third volume, Ted, Jane and Hubert have toned down considerably, although Ted's temper and bossiness haven't abated. Frustrated by her lack of rights and privileges compared to those of her older brothers, especially when she's continually insulted by the same, Edie feels she must rebel and, at times, take revenge against those who deem her unworthy of consideration. Her best friend Susan, a minister's daughter, tries to teach her to rely on God to supply her needs, although Edie is convinced God is primarily concerned with helping boys, not girls like herself. When the teacher hired to teach Edie and Susan refuses to teach them arithmetic because they are girls, Edie drops all their books out the attic window--certainly not a rational response by today's standards, but Spykman is willing to show her characters both succeed and fail. Edie risks considerable danger at the shore by taking a boat out alone and dares to punch a cop during a suffragettes parade. She eventually manages to prove her worth to her family by a risky manuever with a neighbor's bull.

Occasionally I'll check my stats and see that someone's been here searching for information on E. C. Spykman, so I can't be the only person who read and continues to love these books. Why can't they be brought back into print so that a new generation of readers can fall under their spell?

Reviews at time of publication

New York Times, October 23, 1955, review of A Lemon and a Star

On p. 1 of this book we learn that Jane, celebrating her tenth birthday, had left home "with the thought of living in a tree, because Theodore had said he was going to kill her." On this realistist note we are introduced to the four Cares children, probably the most uninhibited youngsters in fiction since Richard Hughes wrote "The Innocent Voyage." There are the terrible-tempered Theodore; Jane, tough, resilient and yet a little wistful; unpredictable Hubert; and Edie, the dainty, bratty, baby sister.

Living a rather isolated existence in the country, they court death constantly; Jane falls in the reservoir and Hubert is nearly killed by a swarm of hornets; a secret steeplechase nearly wipes them all out. They are constantly at war among themselves, yet when adults seem to threaten their rights and privileges, they close ranks in the secret fraternity of childhood. Their attitude toward their widowed father is one of watchful neutrality and that aloof figure deserves nothing more. In short, this is not a story for those who want cozy cliches about family life. It is, however, an almost starkly honest portrayal of relationships among passionate, individualistic, unrestrained children and as such is frequently moving, often very funny. Even though certain of the episodes are too drawn out and over-written, the essential vitality of these youngsters remains.

--Ellen Lewis Buell

New York Times May 19, 1957 review of The Wild Angel

In A Lemon and A Star E.C. Spykman introduced us to the redoubtable Cares children—Theodore, Jane, Hubert and Edie—as unruly a crew as ever shattered the peace of the early Nineteen Hundreds. In this sequel they are still courting disaster each according to his or her highly individual temperament but their escapades are more along straight comedy lines. Their fraternal warfare and their intermittent rebellion against adult authority are not quite so violent—after all, they are nearly a year older now and Madam the admired stepmother, has brought a measure of order into their lives.

Still, each retains his fierce independence and each has his moments of desperation. For instance, Theodore stages a selfless revolt against the Government on behalf of unappreciated nighbors. Jane is exiled to a girls' school in turn and endures agonies from the attentions of an unwanted, persistent, silent admirer. It is in such episodes that Mrs. Spykman cuts down into the living tissues of children's sensibilites. As for lighter moments, they are done with a fine wit, a keen sense of comic actions and dialogue. The Cares are a formidable family truly, and perhaps not for everybody but they live with an intensity that makes them very real.

--Ellen Lewis Buell, May 19

New York Times Book Review May 22, 1960 review of Terrible, Horrible Edie

Edie, as readers of E. C. Spykman's A Lemon and a Star and The Wild Angel are unlikely to forget, is the fourth of the Cares children, those uninhibited, nonconformist youngsters of the early Nineteen Hundreds. We first knew her as a spoiled, very feminine and convincingly bratty child of 5. Now Edie is 10, tomboyish, still bratty (but in a likeable fashion) and very intense. Running true to the Cares pattern, she is continually in rebellion—against grown-ups (naturally), against the old siblings, and sometimes just against boredom.

When Edie breaks out, there is always plenty of excitement. There is the time she takes her very small half-sisters sailing—a gesture of defiance which nervous parents had better skip—and there is her unauthorized solitary sailing expedition to an island. These episodes ring true as does the final one, which is funny, poignant and tender. Certain others, such as the family hegira to the shore and a burglary, seem somehow extravagant, closer to farce than reality, so that as a whole the book lacks the emotional substance and some of the bite of the earlier ones. Even so, the Cares children have as much vigor and elan that a less-than-perfect story about them is better than no story.

--Ellen Lewis Buell

New York Times Book Review June 5, 1966, review of Edie on the Warpath

Edie was a rebel. The more her brothers tried to put her in her place the more she asserted herself. There is not much a girl of 11 can do against the dominant male sex, but Edie was bold and resourceful and had a lot of confusion spread by her pranks.

Her adventures are set in 1913, and those more spacious and leisurely days are recalled with inulgent charm and piquant detail. The scene ranges from a hilltop in Massachusetts to Florida (a journey that took three days by train then), both described with warm feeling for natural beauty. Adults are seen from Edie's point of view and the fact that she was often wrong in her hasty judgments adds to the comicality of the tale. The family background is realistic for the period and up to date as regards sibling rivalry.

A perfect magnet for trouble, even when she is trying to be good, Edie is not the sort of child teachers exactly welcome to a class, but children will rejoice in her high spirits and she will wring from older readers reluctant admiration. A previous volume about her was titled Terrible, Horrible Edie. That is not fair. She is merely a bright child impatient to grow up quickly and be taken seriously. One feels sure she will turn out well.

--Arleen Pippett

From The Times Literary Supplement, May 25, 1967:

If girls enjoy a period piece (the time is 1913) they will adopt eleven-year-old Edie, the tomboy middle child of a wealthy family whose high spirits make her the despair of all adults and her brothers. A rumbustiousness in the practical jokes, the all-or-nothing love and hate, a humorous appreciation of the folly of grown-ups in dealing with the young give this book a certain distinction. It may remain, however, a collector's piece.

On p. 1 of this book we learn that Jane, celebrating her tenth birthday, had left home "with the thought of living in a tree, because Theodore had said he was going to kill her." On this realistist note we are introduced to the four Cares children, probably the most uninhibited youngsters in fiction since Richard Hughes wrote "The Innocent Voyage." There are the terrible-tempered Theodore; Jane, tough, resilient and yet a little wistful; unpredictable Hubert; and Edie, the dainty, bratty, baby sister.

Living a rather isolated existence in the country, they court death constantly; Jane falls in the reservoir and Hubert is nearly killed by a swarm of hornets; a secret steeplechase nearly wipes them all out. They are constantly at war among themselves, yet when adults seem to threaten their rights and privileges, they close ranks in the secret fraternity of childhood. Their attitude toward their widowed father is one of watchful neutrality and that aloof figure deserves nothing more. In short, this is not a story for those who want cozy cliches about family life. It is, however, an almost starkly honest portrayal of relationships among passionate, individualistic, unrestrained children and as such is frequently moving, often very funny. Even though certain of the episodes are too drawn out and over-written, the essential vitality of these youngsters remains.

--Ellen Lewis Buell

New York Times May 19, 1957 review of The Wild Angel

In A Lemon and A Star E.C. Spykman introduced us to the redoubtable Cares children—Theodore, Jane, Hubert and Edie—as unruly a crew as ever shattered the peace of the early Nineteen Hundreds. In this sequel they are still courting disaster each according to his or her highly individual temperament but their escapades are more along straight comedy lines. Their fraternal warfare and their intermittent rebellion against adult authority are not quite so violent—after all, they are nearly a year older now and Madam the admired stepmother, has brought a measure of order into their lives.

Still, each retains his fierce independence and each has his moments of desperation. For instance, Theodore stages a selfless revolt against the Government on behalf of unappreciated nighbors. Jane is exiled to a girls' school in turn and endures agonies from the attentions of an unwanted, persistent, silent admirer. It is in such episodes that Mrs. Spykman cuts down into the living tissues of children's sensibilites. As for lighter moments, they are done with a fine wit, a keen sense of comic actions and dialogue. The Cares are a formidable family truly, and perhaps not for everybody but they live with an intensity that makes them very real.

--Ellen Lewis Buell, May 19

New York Times Book Review May 22, 1960 review of Terrible, Horrible Edie

Edie, as readers of E. C. Spykman's A Lemon and a Star and The Wild Angel are unlikely to forget, is the fourth of the Cares children, those uninhibited, nonconformist youngsters of the early Nineteen Hundreds. We first knew her as a spoiled, very feminine and convincingly bratty child of 5. Now Edie is 10, tomboyish, still bratty (but in a likeable fashion) and very intense. Running true to the Cares pattern, she is continually in rebellion—against grown-ups (naturally), against the old siblings, and sometimes just against boredom.

When Edie breaks out, there is always plenty of excitement. There is the time she takes her very small half-sisters sailing—a gesture of defiance which nervous parents had better skip—and there is her unauthorized solitary sailing expedition to an island. These episodes ring true as does the final one, which is funny, poignant and tender. Certain others, such as the family hegira to the shore and a burglary, seem somehow extravagant, closer to farce than reality, so that as a whole the book lacks the emotional substance and some of the bite of the earlier ones. Even so, the Cares children have as much vigor and elan that a less-than-perfect story about them is better than no story.

--Ellen Lewis Buell

New York Times Book Review June 5, 1966, review of Edie on the Warpath

Edie was a rebel. The more her brothers tried to put her in her place the more she asserted herself. There is not much a girl of 11 can do against the dominant male sex, but Edie was bold and resourceful and had a lot of confusion spread by her pranks.

Her adventures are set in 1913, and those more spacious and leisurely days are recalled with inulgent charm and piquant detail. The scene ranges from a hilltop in Massachusetts to Florida (a journey that took three days by train then), both described with warm feeling for natural beauty. Adults are seen from Edie's point of view and the fact that she was often wrong in her hasty judgments adds to the comicality of the tale. The family background is realistic for the period and up to date as regards sibling rivalry.

A perfect magnet for trouble, even when she is trying to be good, Edie is not the sort of child teachers exactly welcome to a class, but children will rejoice in her high spirits and she will wring from older readers reluctant admiration. A previous volume about her was titled Terrible, Horrible Edie. That is not fair. She is merely a bright child impatient to grow up quickly and be taken seriously. One feels sure she will turn out well.

--Arleen Pippett

From The Times Literary Supplement, May 25, 1967:

If girls enjoy a period piece (the time is 1913) they will adopt eleven-year-old Edie, the tomboy middle child of a wealthy family whose high spirits make her the despair of all adults and her brothers. A rumbustiousness in the practical jokes, the all-or-nothing love and hate, a humorous appreciation of the folly of grown-ups in dealing with the young give this book a certain distinction. It may remain, however, a collector's piece.

An excerpt from Edie on the Warpath

What to do with Edith Cares for the winter of 1913, when she was eleven years old, was causing the John Cares family of Summerton, Massachusetts, more trouble than she would probably ever be worth. At least this was the opinion of her brother Theodore, who gave it freely when he came home on weekends from college.

"And if you keep on clicking your jaw at people when you chew," he added at Sunday lunch after the roast beef had been served, "even a reform school won't take you."

The reason Edie could not stay at home this winter was because Madam, her stepmother, had begun to have attacks of asthma and would have to go to Florida for her bronichial tubes. Madam's children, The Fair Christine and Lou, who were not very old, only six and four, could go with her because they had Hood, their nurse, to take care of them. Edie's other brother, Hubert, was in the sixth form at his boarding school, so he was all right, and Jane, her older sister, had become a social butterfly who was supposed to lure men into taking her to football games, dances, and balls. "Quite a job at that," as Hubert remarked—especially when she was meant to take care of Father in the time left over. Therefore, there was no one who could pay attention to Edie.

Usually, any Cares who had needed more time and attention and more education at the age of eleven had been sent to their grandfather's in Charlottesville after he had moved to town for the winter and had lived in his third floor room with gas jets and black cupboards, roller-skating every day to a good Charlottesville school. This time Grandfather had drawn the line at Edie. He was too old now for that sort of thing, he had told Father.

"Well, what sort of thing?" Edie asked, clicking her jaw at Theodore because he kept his eyes on her.

She was not particularly anxious herself to go to Grandfather's. She drew the line at him, too. Whenever they played Old Maid together and he won, he looked at her through the bottom of his spectacles as if it meant something, and whenever she won and looked at him, he sat back in his chair and said: "But I can't be, I've been married already." Was that fair?

So she did not mind not going to Grandfather's. What she did mind was being shunted around like an old railroad car that no one wanted to see coming down the track, so she would really like to know what sort of thing kept everyone going on and on about her, the way they did about the Suffragettes or President Wilson.

Even if they had been willing to listen, Edie would not have considered telling them why she particularly wanted to stay at home this winter. In the first place, she herself approved of her own school, Miss Lincoln's. All the Cares children had been to her and knew about her parrot, and how she baked cookies three times a week. For herself, something extra had been added, Edie knew—outside crusts of fresh bread with butter and honey at recess. "For an exceptionally good child." So how did they like that!

In the second place, Susan Stoningham, her best friend, had come to live just up the road, or, if you went across lots, only as far as two fields, a swamp, and a lawn away.

In the third, fourth, fifth, and all the other places, Edie liked the new house they were living in. Father had built it. Nobody had wanted to leave the Red House in the valley where they had all been born and grew up. Even Edie herself had lived there for nine years. But Father had thought that being on the highest hill in Summerton would be good for Madam's breathing, so the Red House had vanished and there was the Lawn House instead. Edie liked it. Everybody liked it. It had big rooms, big halls, big corridors. Madam had done them in green and white and gold, and her own parlor was rose, as Mother's had been in the Red House. Even Theodore thought this was tactful. They all had rooms of their own, and the boys had the whole top floor away from everybody.

"And that's the most tactful," Edie said to Hubert one day as they were walking down the hall to the library. He didn not get mad but only tripped her up and left her on the floor.

From Edie's own room—indeed from any room in the house if you looked out the right window—you could see almost the whole of the west end of Summerton; the meadows that made up the family dairy farms, the chain of Reservoir basins that took water to Charlottesville, the woods that were on top of the small hills, and the scattered valley trees—giant oaks and elms and maples that the cows stood under—and the masses of corn steeped in the sun and baking. That had been this summer. The sun and wind had seemed to be everywhere in this house, so that it smelled of flowers, hay, and now in September, corn. She wanted to be in it when it smelled of snow. If there should be an ice storm, she would be able to see every branch and twig for miles. She even looked forward to mud. There was a foot scraper between two horseshoes fastened to the stone outside the front door. It had never been used yet. She meant to christen it the first time she broke through the swamp ice on her way back from Susan's. Hobbling back from the stables (which Father had put quite a way from the house to keep the house air pure), with a stone in her jodhpur boots, she kept stopping to breathe in the late afternoon air. It had been a marvelous ride. She and Susan had cantered up and down, around and around the soft clay roads of Aunt Charlotte's demesne. On the way home, while the horses were cooling, they had chanted their chant.

"I love Summerton.

"I love the trees.

"I love the grass.

"I love the dirt.

"I love the water.

"I love the stones.

"I love the woodchucks.

"I love the snakes.

"I love the mosquitoes."

In Susan's opinion, you couldn't go further than that because mosquito bites swelled her up.

There would be three horses for them to ride this winter when the others weren't home. There would be Widgy, her small brown dog to take to the Reservoir looking for muskrats. There would be Susan's rabbits—well, they weren't much, but they had little rabbits that got to look like marshmallows. There would be football games at Hubert's school—that was in Summerton because it had been started by Mother's father—and it was, very conveniently, not far from the Lawn House. You could see a hundred boys in a single afternoon. There would be—Heavens, of course she could not leave home. She had forgotten the most important thing of all. Susan, whose father was a minister, was teaching her religion. When Grandfather was in Summerton, Edie went to church with him every Sunday. She had fallen in love with Greg Robinson, the boy who carried the cross at church, and was doing her best to persuade God to make him look at her—just once.

With this sort of private life going on, Edie could not see how anyone could expect her to leave Summerton. They did, though. Aunt Charlotte had asked Father if he wished his daughter to grow up a hottentot, and when he had to say "no," she said she would be back when she had thought things over.

"And heaven knows," Hubert had said, "what dark plot she may be hatching."

The other relations, who belonged to Mother, attacked Madam on the sly. They called her on the telephone about Edie's riding pants and her hair—particularly her hair. Edie did not think her hair was bad; it was thick and yellow and went with her blue eyes, but she had chopped it off last summer with the carving knife, and to keep it out of her eyes, she pushed it back behind her ears. It made her look, they said, like a young tiger cat.

"Not bad at that," said Hubert, when he heard it.

It had been a pleasure to snarl at him, and it was a pleasure to keep arguing with everybody.

"I just want to stay here. Why can't I?"

"If you say that again, I'll—"

"I'll say it till I'm dead. Why can't I? Why can't I?"

"All right," said Theodore. "Look—do you really want to know?"

"Yes!"

"All right, I'll tell you," said Theodore, bracing his hands on the table so that he lifted himself a little. "You are nothing but a girl and have to be taken care of. You're the weaker sex, and all you'll ever be able to do is your knitting. Why don't you get that into your silly noodle so we can have some peace?"

--E.C. Spykman

"And if you keep on clicking your jaw at people when you chew," he added at Sunday lunch after the roast beef had been served, "even a reform school won't take you."

The reason Edie could not stay at home this winter was because Madam, her stepmother, had begun to have attacks of asthma and would have to go to Florida for her bronichial tubes. Madam's children, The Fair Christine and Lou, who were not very old, only six and four, could go with her because they had Hood, their nurse, to take care of them. Edie's other brother, Hubert, was in the sixth form at his boarding school, so he was all right, and Jane, her older sister, had become a social butterfly who was supposed to lure men into taking her to football games, dances, and balls. "Quite a job at that," as Hubert remarked—especially when she was meant to take care of Father in the time left over. Therefore, there was no one who could pay attention to Edie.

Usually, any Cares who had needed more time and attention and more education at the age of eleven had been sent to their grandfather's in Charlottesville after he had moved to town for the winter and had lived in his third floor room with gas jets and black cupboards, roller-skating every day to a good Charlottesville school. This time Grandfather had drawn the line at Edie. He was too old now for that sort of thing, he had told Father.

"Well, what sort of thing?" Edie asked, clicking her jaw at Theodore because he kept his eyes on her.

She was not particularly anxious herself to go to Grandfather's. She drew the line at him, too. Whenever they played Old Maid together and he won, he looked at her through the bottom of his spectacles as if it meant something, and whenever she won and looked at him, he sat back in his chair and said: "But I can't be, I've been married already." Was that fair?

So she did not mind not going to Grandfather's. What she did mind was being shunted around like an old railroad car that no one wanted to see coming down the track, so she would really like to know what sort of thing kept everyone going on and on about her, the way they did about the Suffragettes or President Wilson.

Even if they had been willing to listen, Edie would not have considered telling them why she particularly wanted to stay at home this winter. In the first place, she herself approved of her own school, Miss Lincoln's. All the Cares children had been to her and knew about her parrot, and how she baked cookies three times a week. For herself, something extra had been added, Edie knew—outside crusts of fresh bread with butter and honey at recess. "For an exceptionally good child." So how did they like that!

In the second place, Susan Stoningham, her best friend, had come to live just up the road, or, if you went across lots, only as far as two fields, a swamp, and a lawn away.

In the third, fourth, fifth, and all the other places, Edie liked the new house they were living in. Father had built it. Nobody had wanted to leave the Red House in the valley where they had all been born and grew up. Even Edie herself had lived there for nine years. But Father had thought that being on the highest hill in Summerton would be good for Madam's breathing, so the Red House had vanished and there was the Lawn House instead. Edie liked it. Everybody liked it. It had big rooms, big halls, big corridors. Madam had done them in green and white and gold, and her own parlor was rose, as Mother's had been in the Red House. Even Theodore thought this was tactful. They all had rooms of their own, and the boys had the whole top floor away from everybody.

"And that's the most tactful," Edie said to Hubert one day as they were walking down the hall to the library. He didn not get mad but only tripped her up and left her on the floor.

From Edie's own room—indeed from any room in the house if you looked out the right window—you could see almost the whole of the west end of Summerton; the meadows that made up the family dairy farms, the chain of Reservoir basins that took water to Charlottesville, the woods that were on top of the small hills, and the scattered valley trees—giant oaks and elms and maples that the cows stood under—and the masses of corn steeped in the sun and baking. That had been this summer. The sun and wind had seemed to be everywhere in this house, so that it smelled of flowers, hay, and now in September, corn. She wanted to be in it when it smelled of snow. If there should be an ice storm, she would be able to see every branch and twig for miles. She even looked forward to mud. There was a foot scraper between two horseshoes fastened to the stone outside the front door. It had never been used yet. She meant to christen it the first time she broke through the swamp ice on her way back from Susan's. Hobbling back from the stables (which Father had put quite a way from the house to keep the house air pure), with a stone in her jodhpur boots, she kept stopping to breathe in the late afternoon air. It had been a marvelous ride. She and Susan had cantered up and down, around and around the soft clay roads of Aunt Charlotte's demesne. On the way home, while the horses were cooling, they had chanted their chant.

"I love Summerton.

"I love the trees.

"I love the grass.

"I love the dirt.

"I love the water.

"I love the stones.

"I love the woodchucks.

"I love the snakes.

"I love the mosquitoes."

In Susan's opinion, you couldn't go further than that because mosquito bites swelled her up.

There would be three horses for them to ride this winter when the others weren't home. There would be Widgy, her small brown dog to take to the Reservoir looking for muskrats. There would be Susan's rabbits—well, they weren't much, but they had little rabbits that got to look like marshmallows. There would be football games at Hubert's school—that was in Summerton because it had been started by Mother's father—and it was, very conveniently, not far from the Lawn House. You could see a hundred boys in a single afternoon. There would be—Heavens, of course she could not leave home. She had forgotten the most important thing of all. Susan, whose father was a minister, was teaching her religion. When Grandfather was in Summerton, Edie went to church with him every Sunday. She had fallen in love with Greg Robinson, the boy who carried the cross at church, and was doing her best to persuade God to make him look at her—just once.

With this sort of private life going on, Edie could not see how anyone could expect her to leave Summerton. They did, though. Aunt Charlotte had asked Father if he wished his daughter to grow up a hottentot, and when he had to say "no," she said she would be back when she had thought things over.

"And heaven knows," Hubert had said, "what dark plot she may be hatching."

The other relations, who belonged to Mother, attacked Madam on the sly. They called her on the telephone about Edie's riding pants and her hair—particularly her hair. Edie did not think her hair was bad; it was thick and yellow and went with her blue eyes, but she had chopped it off last summer with the carving knife, and to keep it out of her eyes, she pushed it back behind her ears. It made her look, they said, like a young tiger cat.

"Not bad at that," said Hubert, when he heard it.

It had been a pleasure to snarl at him, and it was a pleasure to keep arguing with everybody.

"I just want to stay here. Why can't I?"

"If you say that again, I'll—"

"I'll say it till I'm dead. Why can't I? Why can't I?"

"All right," said Theodore. "Look—do you really want to know?"

"Yes!"

"All right, I'll tell you," said Theodore, bracing his hands on the table so that he lifted himself a little. "You are nothing but a girl and have to be taken care of. You're the weaker sex, and all you'll ever be able to do is your knitting. Why don't you get that into your silly noodle so we can have some peace?"

--E.C. Spykman

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or to

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous---

Almost, at times, the Fool.

Oops, sorry, Prufrock's not the literary reference encountered in a bit o' politics this hot Sunday morning, though it would have done just as well in the following:

"Next to White House courtiers of their rank, Mr. Wilson is at most a Rosencrantz or Guildenstern. The brief against the administration's drumbeat for war would be just as damning if he'd never gone to Africa. But by overreacting in panic to his single Op-Ed piece of two years ago, the White House has opened a Pandora's box it can't slam shut. Seasoned audiences of presidential scandal know that there's only one certainty ahead: the timing of a Karl Rove resignation. As always in this genre, the knight takes the fall at exactly that moment when it's essential to protect the king." (New York Times)

Actual content on this site available later today, I promise.

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or to

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous---

Almost, at times, the Fool.

Oops, sorry, Prufrock's not the literary reference encountered in a bit o' politics this hot Sunday morning, though it would have done just as well in the following:

"Next to White House courtiers of their rank, Mr. Wilson is at most a Rosencrantz or Guildenstern. The brief against the administration's drumbeat for war would be just as damning if he'd never gone to Africa. But by overreacting in panic to his single Op-Ed piece of two years ago, the White House has opened a Pandora's box it can't slam shut. Seasoned audiences of presidential scandal know that there's only one certainty ahead: the timing of a Karl Rove resignation. As always in this genre, the knight takes the fall at exactly that moment when it's essential to protect the king." (New York Times)

Actual content on this site available later today, I promise.

Friday, July 15, 2005

"My God, that bloody casket has fallen on the floor! Some people were hammering in the next flat and it fell off its bracket. The lid has come off and whatever was inside it has certainly got out. Upon the demon-ridden pilgrimage of human life, what next I wonder?"

--Iris Murdoch, The Sea, the Sea

Murdoch was born in Dublin on this date in 1919.

--Iris Murdoch, The Sea, the Sea

Murdoch was born in Dublin on this date in 1919.

Thursday, July 14, 2005

Earlier this week while trying to figure out what exactly the "chelengk" on Jack Aubrey's hat was supposed to be (obviously made of diamonds) and not finding the word in either the Oxford American or the OED, I googled "chelengk" and discovered Lubbers' London - The Master And Commander Museum Trail. Also possibly of interest to Maturin and/or natural history fans is Snail's Tales, which I've been enjoying for a couple of weeks now.

Wednesday, July 13, 2005

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the menfolk in the South love their pickup trucks. Still and all, the owner of this one comes across a tad bit excessive in the display of this love. Since he had the portrait of his lady love airbrushed onto the area above the front wheels (no, I don't know the specialized precise term for that area, but I can locate a chestnut and a frog on a horse) and this scene on the back (which reveals he also is a religious man partial to Rottweilers), he's had a front license plate airbrushed with another picture of the truck. Where next? The cab doors? The hood?

We get it already. You love your shiny red pickup truck.

I'd carry an awful lot of insurance on it if I were you.

More substantial (ha!) blogging will resume once the @%*#$ migraine in my @#%*$ left temple finds somewhere better to be.

Tuesday, July 12, 2005

A few quotations from Henry David Thoreau, born today in 1817:

Books are the treasured wealth of the world and the fit inheritance of generations and nations.

Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand instead of a million count half a dozen, and keep your accounts on your thumb-nail.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.

There is no value in life except what you choose to place upon it and no happiness in any place except what you bring to it yourself.

Do not be too moral. You may cheat yourself out of much life so. Aim above morality. Be not simply good; be good for something.

Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads.

The squirrel that you kill in jest, dies in earnest.

However mean your life is, meet it and live it: do not shun it and call it hard names. Cultivate poverty like a garden herb, like sage. Do not trouble yourself much to get new things, whether clothes or friends. Things do not change, we change. Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts.

I have never found a companion that was so companionable as solitude. We are for the most part more lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our chambers. A man thinking or working is always alone, let him be where he will.

The price of anything is the amount of life you exchange for it.

If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.

Books are the treasured wealth of the world and the fit inheritance of generations and nations.

Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand instead of a million count half a dozen, and keep your accounts on your thumb-nail.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.

There is no value in life except what you choose to place upon it and no happiness in any place except what you bring to it yourself.

Do not be too moral. You may cheat yourself out of much life so. Aim above morality. Be not simply good; be good for something.

Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads.

The squirrel that you kill in jest, dies in earnest.

However mean your life is, meet it and live it: do not shun it and call it hard names. Cultivate poverty like a garden herb, like sage. Do not trouble yourself much to get new things, whether clothes or friends. Things do not change, we change. Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts.

I have never found a companion that was so companionable as solitude. We are for the most part more lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our chambers. A man thinking or working is always alone, let him be where he will.

The price of anything is the amount of life you exchange for it.

If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.

Monday, July 11, 2005

Riches

Readerville orphan received today:

Lisa Dalby's The Tale of Murasaki

ILLs waiting for me at the circ desk:

Dawn Powell's The Bride's House

Maxine Kumin's Jack and Other New Poems

ILL not yet arrived:

Gabriel Josipovici's Moo Pak

Amazon reward certificate shipment:

Orhan Pamuk's Istanbul

William Faulkner's The Unvanquished

Lisa Dalby's The Tale of Murasaki

ILLs waiting for me at the circ desk:

Dawn Powell's The Bride's House

Maxine Kumin's Jack and Other New Poems

ILL not yet arrived:

Gabriel Josipovici's Moo Pak

Amazon reward certificate shipment:

Orhan Pamuk's Istanbul

William Faulkner's The Unvanquished

Recent reads

By accident I pressed the wrong button on the audio thingie last night and lost my place in Jackson's Dilemma; I read the last 80 or so pages this morning instead of attempting to locate my place again since I was ready to be done with this one anyway. I have a feeling I'll be doing a lot of half-listening/half-reading of books in the future. Next up: Patrick O'Brian's Treason's Harbour--it should make for most enjoyable listening.

After finishing two enormous novels back to back--Pinkerton's Sister and The Historian--I've opted for shorter fare these last few days. I'd not heard of Susan Glaspell before I spotted a review of her latest biography in the New York Times a few weeks back and, curious, I promptly placed a hold at the public library on her Pulitzer-winning play Alison's House and checked out collections of her shorter plays and stories from the university. I'm glad I did. I've read two plays and a handful of short stories at this point, and hope to read at least one more play and a few more stories. I particularly liked "'Finality' in Freeport," the story of a censorship fight with a library board that refused to purchase a particular title:

I'm revisiting some children's novels and trying to decide what I want to commit to next.