I first heard of Bohumil Hrabal from C. last June, who placed an ILL request on Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age based on something she'd read somewhere. C. didn't read Dancing Lessons (as far as I know), but determined that I ought to since I was the one with a trip to Prague in the immediate future. But after determining that the entire book was one long sentence I decided I was a bit too flighty at that point in time to muster the concentration necessary for such an undertaking. I returned the book unread.

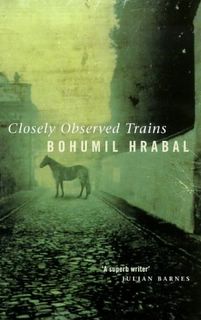

Then in Prague, in the Kafka bookstore that no one went in except for R. and me (because you had to pay to enter), I saw some books by Hrabal again, and chose a couple while R. was selecting an Ivan Klima. I started Klima's No Saints or Angels on the flight home, but ignored Hrabal until this morning when I was feeling the pangs of having too many books in progress—too many books to feel I'm making progress in any of them. Why not start yet another one, but a short one, one I could finish in a few hours? Closely Observed Trains is a mere 91 pages? Perfect!

And it was. I love this book. It's the story of a young Czech, Milos Hrma, who is just returning to his job at a railway station after a three-months leave following a suicide attempt. It's 1945 and the Germans have lost command of the air-space over the town and the country, but the trains, although not running on time, are still carrying S.S. escorts and getting ammunition and other supplies to the front lines.

There's a fabulous chapter that juxtaposes Milos being taken prisoner aboard a close-surveillance military transport with his earlier suicide attempt and the reasons behind it. Milos had traveled by train to a town where he was unknown to kill himself. He passed a bricklayer installing a fire extinguisher in the hall of the hotel who was whistling a waltz and began to whistle the same waltz himself as he got out his razors in his room and ran his bath. Before getting in the bath, he opened the door a crack and made eye contact with the bricklayer. It was this moment of connection that led to his rescue, and it's that moment of connection with the scar-faced German captain on the train, who notices the scars on Milos' wrists, that results in Milos' release.

A similar moment of shared humanity comes at the end of the novel after Milos becomes involved in an attempt to blow up a train loaded with ammunition, the very night Dresden is air-bombed and the station is flooded with Germans "who looked as though they'd escaped from a concentration camp, for they all had on striped trousers, but when they came into the office we could see that these were people in striped pyjamas, with only coats thrown over them, just as they had got away with their bare lives, and they all had fixed eyes that never blinked." Milos feels no pity for them, much less than he has felt previously for mistreated livestock, but after a more personal encounter with a German soldier of low rank comes to the realization that "surely if we could have met somewhere in civil life we might well have liked each other, and found a lot to talk about."

I'll be getting the movie based on the book, Closely Watched Trains (also the American title of the book), from the library in a day or two. It evidently won a few awards back in the 60s. Hrabal helped write the screenplay.

I still have I Served the King of England to read. From what I've heard it's supposed to be even better.

No comments:

Post a Comment