Saturday, April 30, 2005

Best advice I ever got from a literary character

--Louise Fitzhugh, Harriet the Spy

We'll officially be studying poetry for another week at least, but in deference to its being the last day of National Poetry Month, one of my favorite epitaphs from Spoon River Anthology:

MARGARET FULLER SLACK

I would have been as great as George Eliot

But for an untoward fate.

For look at the photograph of me made by Penniwit,

Chin resting on hand, and deep-set eyes--

Gray, too, and far-searching.

But there was the old, old problem:

Should it be celibacy, matrimony or unchastity?

Then John Slack, the rich druggist, wooed me,

Luring me with the promise of leisure for my novel,

And I married him, giving birth to eight children,

And had no time to write.

It was all over with me, anyway,

When I ran the needle in my hand

While washing the baby's things,

And died from lock-jaw, an ironical death.

Hear me, ambitious souls,

Sex is the curse of life!

--Edgar Lee Masters

Via Tingle Alley, a compilation of poetry used in movies from the Michigan Quarterly Review.

Friday, April 29, 2005

Dragging out the baby pictures

Claudie as a kitten.

Remember to check out The Ark on Fridays and the Carnival of the Cats on Sundays for a round up of the best and latest pet blogging photos.

Thursday, April 28, 2005

The interplay between reality and fantasy

The day Quixote and Sancho rode out from their unnamed village, a fictional

blueprint came to life. Don Quixote is our prototypical text, the first story to

emerge out of a self-awareness of its own fictional form, to take as its theme

the gap between appearance and reality; to be, in our terms, modern. It is to

the modern novel what Sigmund Freud is to psychoanalysis. Freud, in fact, was an

admirer of Cervantes: in the summer of 1883 he confessed to his fiancée Martha

Bernays that he was more interested in Don Quixote than in brain anatomy. He

found Quixote's dialogues with Sancho Panza significant for the lesson they

offered of the need both to discriminate between reality and fantasy and to

understand their interplay. He expressed an oddly romantic sympathy for

Quixote's idealism: "Once we were all noble knights passing through the world

caught in a dream, misinterpreting the simplest things, magnifying commonplaces

into something noble and rare, and thereby cutting a sad figure… we men always

read with respect about what we once were and in part still remain." (Prospect)

Firefly

Mal: Define "interesting."

Wash: Oh God oh God we're all going to die.

Pardon the squee, but the trailer for Serenity is on line (via the Modulator) and unless I'm mistaken will also be shown on the big screen tomorrow when Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy premieres.

I'd firmed my conviction to read Joy based on an early glimpse of Henry, an elderly man planning to kill himself, who "retained a good head for the words of others even as his own words, particularly after the last stroke, sometimes eluded him." Later in the novel, his suicide attempt prevented by another stroke, Henry manages to distance himself from the humiliation of having Lev, his grown son, change his diaper by reciting the Gettysburg Address, while Lev wonders what the prayer is that his father is muttering.

I flashed back to a similar situation in The Sleeping Father. Bernard Schwartz has also suffered a stroke, his brought on by a pharmacist's error, and is experiencing aphasia as well. His teenage son Chris visits him in the rehab center and reads—and explains in his off-kilter way—William Butler Yeats' "Leda and the Swan." The scene itself really isn't comparable to Rosen's since Sharpe proceeds with great black humor to juxtapose Bernie's doctor reading him "The Second Coming" with Chris's, ah, tryst with a speech pathologist in her office down the hall. Rosen uses his scene to lead to Lev's realization that God, "however much He might or might not exist, played no role whatsoever in human affairs." Lev's rabbi girlfriend Deborah, who is actually the novel's main character, will experience her own dark night of the soul beginning in the very next chapter.

Since all but one of the people Rosen thanks on the acknowlegments page are women you'd think someone would have told him to watch for overkill in the tears department. He must have assumed the psalm saying "weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes in the morning" gave him tacit permission for an otherwise strong character to spend much of her time in tears. I don't know that I've encountered such a crier in literary fiction since Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss. Interestingly enough, Rosen, whose own wife is a rabbi, says he was affected by Dinah, the charismatic Methodist from Adam Bede, in his portrayal of Deborah (Nextbook). Since I've yet to read Adam Bede, I don't know if Dinah weeps profusely as well.

A hundred or so pages to go. It's definitely worth reading despite my quibbles with Shifting Perspective and Characters Who Cry Too Much.

Wednesday, April 27, 2005

Self publishing and print on demand

Patry Francis writes:

"What if a small number of writers, say five or ten, banded together and created their own imprint, using one of the big self-publishing companies as a vehicle? What if those writers edited each other, supported each other, and put all their creative ideas, their contacts, and blogging skills into marketing each other? Isn't that really the next step in the revolution that began with little blogs just like mine, many of which have now become real cultural forces?

"Is it the best idea I ever had? Or just another fatuous writer's dream? You decide. Because for the first time ever, you have the power."

Monday, April 25, 2005

The ALA's official statement about the Patriot Act.

The Campaign for Reader Privacy. Sign a petition; send an email to your representatives in Congress.

And when you're in the mood for terrorists in libraries in fiction: Mark Swartz's Instant Karma.

Excessive excitement

And yay! A new Hilary Mantel! A treat for everyone.

Sunday, April 24, 2005

"All the time," said Deborah. "You know, when people get sick, or when they are in mourning, or when they face death, they often feel crazy when in fact they're seeing reality very clearly, it's just a different reality from the one they're used to focusing on. Suddenly the routine of denial and habit doesn't help them, it isn't available anymore. Jewish tradition, for me, creates a kind of counter-routine that doesn't dissolve in a crisis. So that you're not suddenly looking down and discovering in a shocked way that you're walking on a narrow bridge. Tradition is kind of like the railing of the bridge. The bridge is still narrow and its' still suspended over darkness. But there's something to hold onto that lots of other people have held onto."

--Jonathan Rosen, Joy Comes in the Morning

Silence

"Superior people never make long visits,

have to be shown Longfellow's grave

or the glass flowers at Harvard.

Self-reliant like the cat--

that takes its prey to privacy,

the mouse's limp tail hanging like a shoelace from its mouth--

they sometimes enjoy solitude,

and can be robbed of speech

by speech which has delighted them.

The deepest feeling always shows itself in silence;

not in silence, but restraint."

Nor was he insincere in saying, "Make my house your inn."

Inns are not residences.

--Marianne Moore

Friday, April 22, 2005

Free vs. formal forms

Hey, no fair. I taught S. how to scan this week. I swore to him it was something he had to know how to do.

Cat blogging + poetry

For he is a mixture of gravity and waggery.

. . . .

For he camels his back to bear the first notion of business.

For he is good to think on, if a man would express himself neatly.

. . . .

For, though he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

. . . .

For every house is incomplete without him, and a blessing is lacking in the spirit.

. . . .

For he is of the tribe of Tiger.

. . . .

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skin and glaring eyes.

. . . .

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

--Christopher Smart, excerpts from Jubilate Agno

Friday morning bird blogging

Trevor, the Indian ringneck of the house.

Remember to check out The Ark on Fridays and the Carnival of the Cats on Sundays for a round up of the best and latest pet blogging photos.

Thursday, April 21, 2005

The Bagel

rolling away in the wind,

annoyed with myself

for having dropped it

as if it were a portent.

Faster and faster it rolled,

with me running after it

bent low, gritting my teeth,

and I found myself doubled over

and rolling down the street

head over heels, one complete somersault

after another like a bagel

and strangely happy with myself.

--David Ignatow

Wednesday, April 20, 2005

The Waking

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Of those so close beside me, which are you?

God bless the Ground! I shall walk softly there,

And learn by going where I have to go.

Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?

The lowly worm climbs up a winding stair;

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Great Nature has another thing to do

To you and me; so take the lively air,

And, lovely, learn by going where to go.

This shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

--Theodore Roethke

Wouldn't The Peabody Sisters dovetail nicely with Emerson Among the Eccentrics?

Tuesday, April 19, 2005

Henderson the Rain King

Memo to self: renew subscription to NYer.

"As much a disease as he is a man” perfectly sums up “Henderson the Rain King.” [Bellow is alluding to a description of Henderson I’d used in my question.] Henderson is of course looking for a cure. But the bourgeois is defined by his dread of death. All we need to know about sickness as it relates to bourgeois amour propre and death we can learn from Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain.” The difficulty in approaching Henderson following this outlook is that Henderson is so unlike a bourgeois. In his case, the categories wither away.

It seems to me that I didn’t know what I was doing when I wrote “The Rain King.” I was looking for my idea to reveal itself as I investigated the phenomena—the primary phenomenon being Henderson himself, and it presently became clear to me that America has no idea—not the remotest—of what America is. Europeans would agree, enthusiastically, with this finding. They will tell you that America is inculte or nyekulturny. But how far does that get us? It is true that culture is not one of Henderson’s direct concerns. He could not compete with his father’s gentlemanly generation—his immediate ancestors who knew Homer and read Dante in Italian. He had a very different take on American life. You refer to this, rightly, as his wacky anthropology. To a young Chicagoan it seemed the science of sciences. I learned that what was right among the African Masai was wrong with the Eskimos. Later I saw that this was a treacherous doctrine—morality should be made of sterner stuff. But in my youth my head was turned by the study of erratic—or goofy—customs. In my early twenties I was a cultural relativist. I had given all of that up before I began to write “Henderson.”

Roth likes “Henderson,” and I am grateful to him for that. He sees it as a screwball stunt, but he sees, too, that the stunt is sincere and the book has great screwball authority. I was much criticized by reviewers for yielding to anarchic or mad impulses and abandoning urban settings and Jewish themes. But I continue to insist that my subject ultimately was America. Its oddities were not accidental but substantial. Again, Roth puts it better than I could have done. Henderson is that “undirected human force whose raging insistence miraculously does get through.” The wacky Henderson led me through my last and wackiest course in anthropology. My diploma, if I had been given one, would have told the world that I was a graduate of the college of dionysiacs. Did I know what I was doing? Not very clearly. My objective was to “burst the spirit’s sleep.” Readers would share this—or they would not. Alfred Kazin asked what Jews could possibly know about American millionaires. For my purposes, I felt that I knew enough. Chanler Chapman, the son of the famous John Jay Chapman, was the original of Eugene Henderson—the tragic or near-tragic comedian and the buffoon heir of a great name. I can’t imagine what I saw in him or why it was that I was so goofily drawn to him. Those years were the grimmest years of my life. My father had died, a nephew in the Army had committed suicide. My wife had left me, depriving me also of my infant son. I had sunk my small legacy into a collapsing Hudson River mansion. For the tenth time I went back to page 1, beginning yet another version of “Henderson.”

Frogs

"What do you need frogs for, sir?" one of the boys asked.

"I'll tell you what for," Bazarov replied; he had a special flair for inspiring trust in members of the lower class, although he never indulged them and always treated them in an offhanded manner. "I'll cut the frogs open and look inside to see what's going on; since you and I are just like frogs, except that we walk on two legs, I'll find out what's going on inside us as well."

"What do you want to know that for?"

"So I don't make any mistakes if you get sick and I have to make you better."

"Are you a doctor, then?"

"Yes."

"Vaska, you hear, the gentleman says you and me are just like frogs. How do you like that?"

"I'm afraid of them, of frogs," observed Vaska, a lad about seven, with hair as pale as flax, a gray smock with a stand-up collar, and bare feet.

"What are you afraid of? You think they bite?"

"Come on now, just wade into the water, you philosophers," said Bazarov.

--Ivan Turgenev, Fathers and Sons

R. informed me Sunday that I must read Turgenev by next weekend. Now that I've finished the Chernow and should be able to read the necessary-to-catch-up 50 pages of DQ tonight, I feel I should be able to manage--it's short. I need time to forgive Jonathan Rosen before returning to Joy Comes in the Morning anyway: after forty-odd wonderful pages of close third person perspective, each character's encapsuled in a separate chapter, Rosen abruptly saw fit to begin employing shifting viewpoint on a paragraph by paragraph basis. Ugh. I don't need to know what's going on inside every character every moment; not every frog needs to be dissected on every page.

Monday, April 18, 2005

Judicial review

"The scalding debate over repeal of the Judiciary Act prompted Hamilton to lambast Jefferson in a series of eighteen essays entitled 'The Examination.' Reviving themes from The Federalist Papers, he explained why the judiciary was destined to be the weakest branch of government. It could 'ordain nothing. Its functions are not active but deliberative. . . . Its chief strength is in the veneration which it is able to inspire by the wisdom and rectitude of its judgments.' For Hamilton, Jefferson's desire to overturn the Judiciary Act was an insidious first step toward destroying the Constitution: 'Who is so blind as not to see that the right of the legislature to abolish the judges at pleasure destroys the independence of the judicial department and swallows it up in the impetuous vortex of legislative influence?' Without an independent judiciary, the Constitution was a worthless document."

--Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton

Infared technology leads to Sophocles and Hesiod

Three cheers for infared technology!

"In the past four days alone, Oxford's classicists have used it to make a series of astonishing discoveries, including writing by Sophocles, Euripides, Hesiod and other literary giants of the ancient world, lost for millennia. They even believe they are likely to find lost Christian gospels, the originals of which were written around the time of the earliest books of the New Testament.

"The papyrus fragments were discovered in historic dumps outside the Graeco-Egyptian town of Oxyrhynchus ("city of the sharp-nosed fish") in central Egypt at the end of the 19th century. Running to 400,000 fragments, stored in 800 boxes at Oxford's Sackler Library, it is the biggest hoard of classical manuscripts in the world.

"The previously unknown texts, read for the first time last week, include parts of a long-lost tragedy - the Epigonoi ("Progeny") by the 5th-century BC Greek playwright Sophocles; part of a lost novel by the 2nd-century Greek writer Lucian; unknown material by Euripides; mythological poetry by the 1st-century BC Greek poet Parthenios; work by the 7th-century BC poet Hesiod; and an epic poem by Archilochos, a 7th-century successor of Homer, describing events leading up to the Trojan War. Additional material from Hesiod, Euripides and Sophocles almost certainly await discovery.

"Oxford academics have been working alongside infra-red specialists from Brigham Young University, Utah. Their operation is likely to increase the number of great literary works fully or partially surviving from the ancient Greek world by up to a fifth. It could easily double the surviving body of lesser work - the pulp fiction and sitcoms of the day."

Thanks to Bookish for unearthing this story.

Sunday, April 17, 2005

Weekend hodgepodge

David Quammen's "Was Darwin Wrong?" in last November's National Geographic won in the National Magazine Award's essay category last week. I'd kept the November issue close at hand but didn't get around to reading the essay until Friday night. You can click through Robert Clark's accompanying series of images and read the opening paragraphs of the essay online.

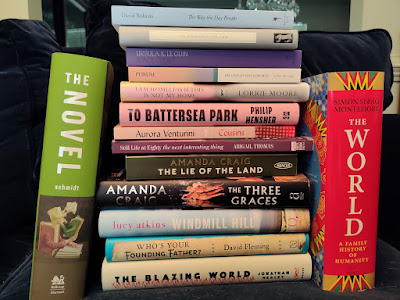

Made a quick trip to the used bookstore on Saturday. Came home with an illustrated hardback version of Beryl Markham's West With the Night, and paperback copies of Saul Bellow's Henderson the Rain King and A.L. Kennedy's Everything You Need. Kennedy has a cool website--her answers to F.A.Q. are most entertaining.

"I decided to write the novel as a chain of plot-and-character studies about how individuals prey on individuals, corporations on employees, tribes on tribes, majorities on minorities, and how present generations 'eat' the sustenance of future generations. Having two narratives set in the past, two in the present and two in the future let me play with historiography and show the 'continental drift' of language. Better still, the structure — in which each narrative is 'eaten' by its successor and later 'regurgitated' by the same — could mirror, and, with luck, enhance the overarching theme."

David Mitchell discusses the genesis of Cloud Atlas in Saturday's Guardian.

Another review of Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go. I'll be reading Ishiguro's latest as soon as I finish Joy Comes in the Morning.

Listened to lectures on T.S. Eliot and "The Wasteland" en route to Chapel Hill on Friday--I'm about ready to attempt a second reading of the poem.

Saturday, April 16, 2005

--Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton

Friday, April 15, 2005

The Convergence of the Twain

I

In a solitude of the sea

Deep from human vanity,

And the Pride of Life that planned her, stilly couches she.

II

Steel chambers, late the pyres

Of her salamandrine fires,

Cold currents thrid, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres.

III

Over the mirrors meant

To glass the opulent

The sea-worm crawls -- grotesque, slimed, dumb, indifferent.

IV

Jewels in joy designed

To ravish the sensuous mind

Lie lightless, all their sparkles bleared and black and blind.

V

Dim moon-eyed fishes near

Gaze at the gilded gear

And query: "What does this vaingloriousness down here?". . .

VI

Well: while was fashioning

This creature of cleaving wing,

The Immanent Will that stirs and urges everything

VII

Prepared a sinister mate

For her -- so gaily great --

A Shape of Ice, for the time fat and dissociate.

VIII

And as the smart ship grew

In stature, grace, and hue

In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too.

IX

Alien they seemed to be:

No mortal eye could see

The intimate welding of their later history.

X

Or sign that they were bent

By paths coincident

On being anon twin halves of one August event,

XI

Till the Spinner of the Years

Said "Now!" And each one hears,

And consummation comes, and jars two hemispheres.

--Thomas Hardy

Peaceful cat. No tax worries. No angst.

Remember to check out The Ark on Fridays and the Carnival of the Cats on Sundays for a round up of the best and latest pet blogging photos.

Wednesday, April 13, 2005

"You are not God. You do not determine the outcome. The outcome is not the point."

"Then what, pray, is the point? His voice was a dry, soft rattle, like a breeze through a bough of dead leaves.

"The point is the effort. That you, believing what you believed-what you sincerely believed, including the commandment 'thou shalt not kill'-acted upon it. To believe, to act, and to have events confound you-I grant you, that is hard to bear. But to believe, and not to act, or to act in a way that every fiber of your sould held was wrong-how can you not see? That is what would have been reprehensible."

and

But I said none of this a year ago, when it might have mattered. It was easy then to convince one's conscience that the war would be over in ninety days, as the president said; to reason that the price paid in blood would justify the great good we were so sure we would obstain. To lift the heel of cruel oppression from the necks of the suffering! Ninety days of war seemed a fair payment. What a corrupt accounting it was. I still believe that removing the stain of slavery is worth some suffering-but whose? If our forefathers make the world awry, must our children be the ones who pay to right it?

and

"Who would hire me to corrupt their daughters' minds? And even if they did, I have not mastered that which I would wish to teach. I have not scaled the cliffs of knowledge, only meandered in the foothills. If I have reached any heights at all in learning, it is as a sparrow-hawk who encountered a favorable breeze that bore it briefly aloft." She flopped down onto the chaise in a flutter of skirt, as unself-conscious as a little girl. "You have unmasked me! I am one of those who knows how I wish the world were; I lack the discipline to make it so."

````

Finished March last night. I'm still mulling it over; a review will follow.

Tuesday, April 12, 2005

Why literature matters and other stuff

It is probably no surprise that declining rates of literary reading coincide with declining levels of historical and political awareness among young people. One of the surprising findings of ''Reading at Risk" was that literary readers are markedly more civically engaged than nonreaders, scoring two to four times more likely to perform charity work, visit a museum, or attend a sporting event. One reason for their higher social and cultural interactions may lie in the kind of civic and historical knowledge that comes with literary reading.

Unlike the passive activities of watching television and DVDs or surfing the Web, reading is actually a highly active enterprise. Reading requires sustained and focused attention as well as active use of memory and imagination. Literary reading also enhances and enlarges our humility by helping us imagine and understand lives quite different from our own.

Indeed, we sometimes underestimate how large a role literature has played in the evolution of our national identity, especially in that literature often has served to introduce young people to events from the past and principles of civil society and governance. Just as more ancient Greeks learned about moral and political conduct from the epics of Homer than from the dialogues of Plato, so the most important work in the abolitionist movement was the novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin."

Likewise our notions of American populism come more from Walt Whitman's poetic vision than from any political tracts. Today when people recall the Depression, the images that most come to mind are of the travails of John Steinbeck's Joad family from ''The Grapes of Wrath." Without a literary inheritance, the historical past is impoverished. (Boston Globe)

With any luck future generations won't judge Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby by what shows up on the big screen: the lastest version is to star Paris Hilton as Daisy Buchanan and Lance Bass from N Sync as Jay Gatsby himself. (BBC)

An interesting array of writers and critics remember Saul Bellow in Slate. I was most interested in what Jonathan Rosen had to say ("That's what Bellow's presence in the world was like, a kind of sheltering genius, because he was able to see the world and transmute it with accuracy and wonder—and the more accurate he was the more wonder you felt, so that mimesis took on an almost mystical aura which, dark as Bellow could be, seemed to suggest something hopeful about the universe, and elevated the role of the writer to the highest possible sphere") since I'll be reading Joy Comes in the Morning in a day or two; and that of Thomas Mellon, who was last seen disparaging Geraldine Brooks' March (which I'll finish before the day's over), now asserting that "any writer" (i.e., Thomas Mellon not being gutsy enough to use first person in his pronouncements) feels "a trace of relief at his passing."

Another novelist who's eschewed magic realism in his writing is Ian McEwan, who has evidently passed that dislike onto the main character in Saturday. In an interview with Salon, McEwan says

One of the privileges of writing novels is to give characters views that you have fleetingly but that are too irresponsible for you ever to defend. You can give them to a character. His views on magical realism, I could never really ... I know there are some great novels in that vein. But still, I do have a streak of skepticism about it. So Henry Perowne could work this up for me on my behalf.

McEwan also questions the worth of contemporary fiction: "If you haven't already read The Charterhouse of Parma or The Secret Agent or The Brothers Karamazov or Middlemarch, why not be reading those?"

A contemporary novel I'll probably read before I ever turn to The Charterhouse of Parma (which, by the way, is the book Karel can never finish in Drabble's The Realms of Gold) is Stewart O'Nan's The Good Wife, reviewed this week by Meg Wolitzer (Washington Post).

And one of these days I'm going to read Temple Grandin's books instead of merely reading about her--this time in Bookslut--because she always comes across as an absolutely fascinating human being.

Monday, April 11, 2005

Goals vs. Reality

Don Quixote--130 pages (to end of First Part)

short stories--read two

March--200 pages

vs.

Alexander Hamilton--60 pages (to p. 500)

Don Quixote--not one word

short stories--Elizabeth Bowen: "Joining Charles" and "The Tommy Crans"

March--80 pages

Not a good weekend for reading.

Sunday, April 10, 2005

'I said pig,' replied Alice; 'and I wish you wouldn't keep appearing and vanishing so suddenly: you make one quite giddy.'

'All right,' said the Cat; and this time it vanished quite slowly, beginning with the end of the tail, and ending with the grin, which remained some time after the rest of it had gone.

--Lewis Carroll

The moon tonight was a Cheshire Cat's grin.

At first S. was too young. Then Nathan Fillion took out Xander's eye in the last season of Buffy and S. deemed it best to avoid all eye injury movies for awhile. Then we waited and waited and waited for the director's cut to come to a theater near us so he could experience it for the first time as it was meant to be seen-which, naturally, happened on a weekend when he had other plans that took precedence.

Last night we finally initiated S. into the family Donnie Darko cult. There was always the possibility that he wouldn't like it, and considering all the elliptical comments he's had to endure since L. and R. and I became obsessive fans, all the playings of "Mad World" he's had to listen to, all the admonishments not to worry if he didn't understand it the first time through-"no one does"-that we didn't mean condescendingly, but sure sounded that way, it's a wonder that he could sit through it, let alone like it.

But he did. All our hype didn't ruin it. He's in the cult! Between the director's cut and Roberta Sparrow's "The Philosophy of Time Travel" at the back of The Donnie Darko Book, he had very few questions-and they were all so very good-- that could not be answered.

Bonus perk: he wants to reread Watership Down. And Graham Greene's "The Destructors."

Saturday, April 09, 2005

Unrealistic reading goals for the weekend

Don Quixote--130 pages (to end of First Part)

short stories--read two

March--200 pages

Friday, April 08, 2005

Claudius Rex

Remember to check out The Ark on Fridays and the Carnival of the Cats on Sundays for a round up of the best and latest pet blogging photos.

Thursday, April 07, 2005

Forty years after its publication journalism students from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln College have studied In Cold Blood and its impact on journalism and literature. Granted exclusive interviews with many who'd refused previously to talk about either the crime or the book, In Cold Blood: A Legacy is the result of their efforts.

Wednesday, April 06, 2005

Weird Don Quixote news

Started March last night; two chapters in I already like it lots more than Year of Wonders.

Since it's National Poetry Month and we're celebrating, er, studying poetry every single day, I'm already very tired of hearing S. tell me that he just doesn't like poetry. It's good for your brain, I keep telling him (link via Book Glutton). Yesterday I added Maxine Kumin's Jack to our selection of Wordsworth poems and it was the hit of the day. Of course, it helped that he'd learn to ride on a horse named Jack and that he knows a couple of roans, but hey, we had a wonderful discussion even once we quit with the horse talk.

A huge number of book lists can be found at Lists of Bests.

Saul Bellow died yesterday at the age of 89. Philip Roth credited him--along with William Faulkner-- with providing "the backbone of 20th century American literature." (SF Chron)

Michiko Kakutani writes, "For all the awards Mr. Bellow received in the course of his career, he saw himself as going against the mainstream of contemporary literature, skeptical of the willful aestheticism and postmodern pyrotechnics that had become increasingly fashionable, and equally dismissive of the trendy nihilism evinced by writers he called 'the wastelanders,' those who believe, in his words, that it is 'enlightened to expose, to disenchant, to hate and to experience disgust.' He believed that literature should hew to one of its original purposes - the raising of moral questions - and his own writing remained firmly indebted to the works he had studied as a boy: the Old Testament, Shakespeare's plays and the great 19th-century Russian novels."

Tuesday, April 05, 2005

Some quick links

A list of Pulitzer winners with reviews/interviews.

Gail Haley, winner of both Caldecott and Kate Greenaway medals for children's books, has donated her medals and an "SUV full" of papers, drawings, and manuscripts to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

In deference to R., who says she hates sites like mine which lure students to them in the hopes of some actual content which they might conceivably put to use in the papers which they have been assigned to write but in actuality offer only LISTS of books read which do such desperately-seeking-substance students NO EARTHLY GOOD: Your Homework Done For Free (via Making Light).

And Michael Berube has some fun at the expense of the Tar Heels.

Monday, April 04, 2005

There's actually a poetry competition in The Ionian Mission and later neither Stephen nor Graham are particularly enthused over the prospects of critiquing the poetical compositions of Naval gentlemen intended for actual publication. Good reading for a Friday night.

Caught up on my Don Quixote reading on Saturday and I'm continuing to find it quite enjoyable, to the point that I could easily read on and not limit myself to three chapters a week. I'm toying with reading on to the end of Book One next weekend and then taking a break for a couple months before continuing on with the others. The crew at 400 Windmills have begun their discussion of DQ and it's been both insightful and informative.

Decided I ought to spend some more time with Alexander Hamilton before beginning another novel; I'm now past the midway mark thanks to the time I spent on the bio on Sunday.

Also read the Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum and Nell Freudenberger stories from the BASS 2004 collection; I loved how both stories relied heavily on other texts--Tobias Wolff and Ray Bradbury--for much of their resonance.

Don't know if I'll make the time to do more than skip through Diane Ravitch's The Language Police, but I did spend some time with her classical literature sampler for high schoolers at the back of the book.

Also read some stuff online about the Fisher King and found a few books of commentary at the library on "The Waste Land." I need to look for a copy of Tennyson's "The Holy Grail," and according to Harold Bloom, I ought to read Whitman's "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" as well.

Won two rounds of Mystery Quotes at Readerville--guessed Ian McEwan the first time, recognized a Guy Vanderhaeghe section from The Last Crossing the second.

Saturday, April 02, 2005

Another mystery quote

On Sunday morning I examined my safeguards, the box of silver dollars I had buried by the creek, and the doll buried in the long field, and the book nailed to the tree in the pine woods: so long as they were where I had put them nothing could get in to harm us. I had always buried things, even when I was small; I remember that once I quartered the long field and buried something in each quarter to make the grass grow higher as I grew taller, so I would always be able to hide there. I once buried six blue marbles in the creek bed to make the river beyond run dry. "Here is treasure for you to bury," C. used to say to me when I was small, giving me a penny, or a bright ribbon: I had buried all my baby teeth as they came out one by one and perhaps someday they would grow as dragons. All our land was enriched with my treasures buried in it, thickly inhabited just below the surface with my marbles and my teeth and my colored stones, all perhaps turned to jewels by now, held together under the ground in a powerful taut web which never loosened, but held fast to guard us.

Friday, April 01, 2005

It rhymes, don't it?

"Jack quite agreed; and he was morally certain that Mowett did not know what a dactyl was either, though he loved him dearly."

--Patrick O'Brian, The Ionian Mission

It's National Poetry Month! I've signed up to receive a poem a day in my email.

The Literary Saloon has taken the time pull the rug out from under Katie Roiphe's claim that few 'cept her had seen fit to mention the connections between Ian McEwan's Saturday and Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway. This New York Times piece about McEwan doesn't mention either Woolf or Tom Wolfe, but links to the Katutani review that does.

At least in the United States loonies who want particular books removed from the shelves usually know that the books in question are actually on the shelves: Orhan Pamuk's detractors in Turkey need to work on that part.

Kazuo Ishiguro's latest, Never Let Me Go, has been getting lots of press. Margaret Atwood's review has made me decide I want to read it sooner rather than later.

Was I sleeping, while the others suffered? Am I sleeping now? To-morrow, when I wake, or think I do, what shall I say of to-day? That with Estragon my friend, at this place, until the fall of night, I waited for Godot?

Remember to check out The Ark on Fridays and the Carnival of the Cats on Sundays for a round up of the best and latest pet blogging photos.

A bang, not a whimper

Two months into L.'s retirement, and I'm finished with the stockpiling of books. No more book purchases! Or at least, no purcha...

-

(See also Musee des Beaux Arts ) As far as mental anguish goes, the old painters were no fools. They understood how the mind, the freakiest ...

-

Lou wondered where his information would go when he died. Would filaments of learning plant patterns on earth? Would his brain train the sin...