Sunday, February 27, 2011

Persephone Reading Weekend: Emma Smith and Margaret Oliphant

Little sheep that I sometimes am, I started collecting Persephone Books in March of 2009. After accumulating eight, I read my first, Julia Strachey's Cheerful Weather for the Wedding, a couple months later. While I certainly enjoyed it, I didn't find it deserving of level of fuss Persephone fans had lavished on these pretty dove-grey books. I ILLed an earlier edition of Christine Longford's Making Conversation, at that time one of the more-recent Persephone reissues, and it was at that point--now that I owned 11--that I began to wonder if I were wasting my time and money on these expensive books. Making Conversation was obviously an inside joke and I just. didn't. get it.

But here I am, participating in a Persephone Weekend, so you know this story's going to turn around, don't you?

Summer of 2009 I read Richmal's Crompton's Family Roundabout and Joanna Cannan's Princes in the Land and I adored the both of them. I have continued to enjoy all the Persphones I've read since, although these two remain my favorites. In fact, I wish Persphone would devote to Crompton the same attention given to Whipple--although I say that as someone who's managed to collect four Whipples without reading a one of them. Yet.

Last week I read one of my very first Persphone purchases, Emma Smith's The Far Cry, the 1949 winner of the James Tait Black Memorial prize for best novel.

He guided the Austin carefully over the planks on to the ferry. He wanted, he urgently wanted to say more, but hesitated, not wishing to antagonise her. He wanted to say: Yes, everything is different; differences are bewildering. Do not, in order to be rid of your bewilderness, attempt to reduce what is extraordinary to the limts of your ordinary appreciation. That is what most people do. They try to commonise, to reduce, because they are afraid of being bewildered. Let yourself be astonished. Be small. That is enough for you, and for me.

It's the story of a 14-year-old, Teresa, who is abruptly pulled from school and taken by her father to stay in India with a married half-sister and her husband. It seems that her father, a teacher, has a lot of unresolved issues where his ex-wife is concerned. When she writes that she'll be returning to England from the States now that her second marriage has ended, he determines, rather dog-in-the-manger-ish style since he doesn't have much of a relationship with their daughter himself, that he's not about to let them meet.

The novel details their hurried preparations, their journey to and through India, and life on a tea plantation, their ultimate destination. There's a lot of gorgeous description of India itself, the country, the people, its customs and celebrations. Midway through the book the focus shifts its focus from Teresa to her half-sister and husband, who despite their love for one another, have a most unhappy marriage, before circling back to Teresa, and where and how she should live.

I'm not in any way doing this book justice, but I highly recommend it!

Yesterday I read a selection from my latest Perspehone purchase--Margaret Oliphant's "Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamond," the second novella published within The Mystery of Mrs Blencarrow. Claire and Desperate Reader both wrote about this one yesterday, so I'll send you off to read their reviews and won't attempt to duplicate another here.

I will say that I am always drawn to stories where the husband, the father of a large brood, walks out on his family without a word of explanation and the woman is left to carry on. (My favorite of these, indeed, one of my all-time favorite novels, is Anne Tyler's Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant. I thought a lot about the Tyler novel yesterday, so much so that I decided that it's time for another reread.)

Unlike many of these stories, Eleanor Lycett-Landon actually undercovers what's behind her husband's disappearance. She decides to make no attempt to get him back; her main concern is to keep the children from learning the truth. There is to be no legal action taken, no attempt at punishing their transgressor. She and the children will have to evade, equivocate, endure the questions asked about why Mr. Lycett-Landon never comes home, but that is Eleanor's choice, made despite the advice of one of her husband's cotton-broker business partners.

'You are mad!' cried the old man. 'You have lost all your good sense, and your feeling too. What, your own husband! you would let him go on living in sin--happy--'

She stopped him with a curious kind of authority--a look before which he paused in spite of himself.

'Happy!' she said; 'I suppose so; at fifty, after living honestly all these years!'

He stopped and shook his grey head. 'I have known such a thing before. It seems as if they must break out--as if common life and duty became insupportable. I have known such a case once before.'

Why worry about punishment, or bringing daddy back home, when there is money enough for every day life to go on satisfactorily, happily, otherwise honestly, without him?

No wonder this Victorian era novella has been called un-Victorian!

I'm definitely interested in reading more works by Margaret Oliphant. I downloaded The Doctor's Family on my Kindle this morning.

And my thanks to Claire and Verity for hosting Persephone Reading Weekend. I would have let these books languish on the shelves for much longer without this little push.

Monday, February 21, 2011

Monday, February 14, 2011

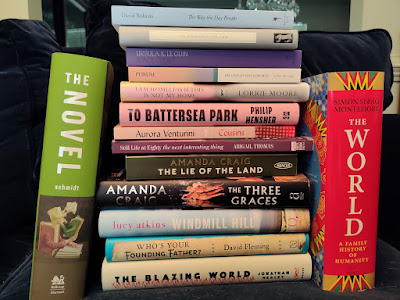

First stockpile of the year

I am trying to limit my book purchases this year to a reasonable number. At various times over the last few weeks, that reasonable number has shifted from an upper limit of two per month to an upper limit of four. If you subtract the book on top, which was a freebie, and Swamplandia, which I preordered in 2010 and therefore doesn't count in this year's purchases, and add one-and-a-half-Kindle downloads (explanation for that down below), I'm restricted from buying anything else for, oh, a couple of weeks.

The book on top of the pile is a "free copy" (it says so on the front cover) of Diana Gabaldon's Outlander. I'm not positive, but I think going to ALA in DC a few years back had something to do with it showing up in the mail. Someone recently recommended the Outlander series to me, so I suppose I ought to read it now that I have my very own copy.

Edith Pearlman's Binocular Vision. A collection of short stories by a North Carolina publishing house. I braved the mall to buy a marked-down calendar in mid-January, and this was my reward for making the trip.

Anthony Powell's A Dance to the Music of Time, second movement. Since I have yet to start on the first movement, I should not have bought this.

Rebecca West's Train of Powder and Family Memories. I don't feel guilty about ordering these one bit.

Karen Russell's Swamplandia! Gators and ghosts and good times ahead!

Jonathan Evison's West of Here. I'm probably the only blogger who didn't request it from the publisher, but I've got a history of buying Algonquin's books that goes way back. I like supporting North Carolina publishing houses.

And for the Kindle: Connie Willis's All Clear and Eleanor Brown's Weird Sisters. I'm counting the Brown as half a purchase since it was my mother-in-law who wanted to buy it (I was happy being on the list for it at the library). I figure we can split the price, though.

Sunday, February 13, 2011

I'm going to stop buying books. . .

Well, maybe not, but I ought to!

Last year there were a lot of changes at the university library including a new book distributor, one that provides us with books that come shelf-ready. Between the budget crisis from the previous year and a focus on filling the faculty's needs, there were long months on end with slim literary pickings on the new books shelves for the likes of me.

Things are much improved now; while there are quite a few worthy books from last year that the library still doesn't have, spotting Charles Baxter, Gryphon, on the shelf last week--just out last month--gives me hope that the lag between publication and purchase isn't to be as great as it's been in the past.

Coming home with me Friday afternoon were:

Joan Silber's The Art of Time in Fiction. Baxter is series editor for the Art of collection, and I thoroughly enjoyed his own contribution, The Art of Subtext, back in 2007.

J. Robert Lennon's Pieces for the Left Hand. Stories of the flash fiction variety.

Barbara Comyns's Who was Changed and Who was Dead. I read Our Spoons Came from Woolworths years back, so I know what a treat this will be. The first sentence: "The ducks swam through the drawing-room windows."

Michael Austin's Useful Fictions: Evolution, Anxiety, and the Origins of Literature. According to the flap, a useful fiction is "a simple narrative that serves an adaptive function unrelated to its factual one."

Anne Carson's An Oresteia. I'm going to listen to all of you and read The Orestia first, but I wanted it on hand nonetheless.

Anthony Trollope's The Fixed Period. This is Trollope's sole venture into dystopian territory, written after he'd presumably read Erewhon.

Louise Penny's The Brutal Telling. C. has been raving about the follow-up to this mystery, Bury Your Dead, which she wants to Kindle-loan to me. But the reviews at Amazon lead me to believe I ought to read this one first.

Percival Everett's Wounded. It's about a horse-trainer in Wyoming and it's been compared to Cormac McCarthy and Walker Van Tilburg Clark. This just might be my choice for C.B.'s western challenge in the spring.

Charles Baxter's Gryphon. New and selected stories.

Joe Sacco's Palestine. A landmark work of comics journalism, according to the cover blurb.

Tomorrow: the books I've bought since the first of the year.

Last year there were a lot of changes at the university library including a new book distributor, one that provides us with books that come shelf-ready. Between the budget crisis from the previous year and a focus on filling the faculty's needs, there were long months on end with slim literary pickings on the new books shelves for the likes of me.

Things are much improved now; while there are quite a few worthy books from last year that the library still doesn't have, spotting Charles Baxter, Gryphon, on the shelf last week--just out last month--gives me hope that the lag between publication and purchase isn't to be as great as it's been in the past.

Coming home with me Friday afternoon were:

Joan Silber's The Art of Time in Fiction. Baxter is series editor for the Art of collection, and I thoroughly enjoyed his own contribution, The Art of Subtext, back in 2007.

J. Robert Lennon's Pieces for the Left Hand. Stories of the flash fiction variety.

Barbara Comyns's Who was Changed and Who was Dead. I read Our Spoons Came from Woolworths years back, so I know what a treat this will be. The first sentence: "The ducks swam through the drawing-room windows."

Michael Austin's Useful Fictions: Evolution, Anxiety, and the Origins of Literature. According to the flap, a useful fiction is "a simple narrative that serves an adaptive function unrelated to its factual one."

Anne Carson's An Oresteia. I'm going to listen to all of you and read The Orestia first, but I wanted it on hand nonetheless.

Anthony Trollope's The Fixed Period. This is Trollope's sole venture into dystopian territory, written after he'd presumably read Erewhon.

Louise Penny's The Brutal Telling. C. has been raving about the follow-up to this mystery, Bury Your Dead, which she wants to Kindle-loan to me. But the reviews at Amazon lead me to believe I ought to read this one first.

Percival Everett's Wounded. It's about a horse-trainer in Wyoming and it's been compared to Cormac McCarthy and Walker Van Tilburg Clark. This just might be my choice for C.B.'s western challenge in the spring.

Charles Baxter's Gryphon. New and selected stories.

Joe Sacco's Palestine. A landmark work of comics journalism, according to the cover blurb.

Tomorrow: the books I've bought since the first of the year.

Saturday, February 12, 2011

I'd ignored all the tweeting furor last week about the author who dissed bloggers until Jeanne weighed in on her blog--these day I'm not going out of my way to find the drama since so much of it seems to cycle around anyway. How many times does anyone need to read the latest version of the Bloggers are Unprofessional story? But of course once I followed Jeanne's link to the offending post I stayed around to read most of the 180 outraged comments despite the fact that I despise pink font.

(I don't care if you write romances or chicklit: proudly proclaim your pink pride with something other than the font, okay? Do you really want to causethe pink eye, eye strain in your readers?)

And then I read the reviewer's post that the author claimed didn't "quantify" why she'd called the plot predictable and the characters one-dimensional as well as all the following comments, including the ones by Anonymous, who seemed so emotionally invested in the book and in putting its detractors in their place that any reasonable person would bet a dollar to a doughnut that Anony had to be the author. By the time I clicked back to the author's blog, looking for additional comments there, she'd deleted them all.

Which of course was her perogative.

And I figured I'd wasted enough time on this particular brouhaha.

But I woke up this morning thinking once again about this:

Oftentimes, the people who set up these kinds of blogs have never written a thing in their lives, except maybe a grocery list. Most are avid readers who think they are qualified to review someone else's work. So it's very sad when they go about damaging the image of upcoming small press and indie authors with the rubbish they write.

and

Please bear in mind that writers work very hard at their craft and the last thing they need is a smartass who makes subjective comments because they don't know how to do anything else.

(Do you see what I mean about the pink font?)

I blog because I'm an avid reader, not because I've published poetry, fiction, journalism. Frankly, I think being an avid reader pretty much takes care of all the qualifications necessary for having a book blog, where basically we all share our thoughts and opinions on what we've read. There are bloggers who gush or snark or journal their way through a book instead of writing the traditional review and they seem to do very well for themselves. There are others who aspire to the Platonic Ideal of reviewing by carefully following the dictates set forth periodically by spokesmembers of the book industry. They market and brand and promote and network and they do very well for themselves, too. There's no right way or wrong way to write about books on a book blog; different approaches will lead to different audiences, that's all.

I don't know this for a fact, but I would assume it's the bloggers who don't have a writing background of some sort that are the most amenable to accepting an ARC from a self-publishing author. I know, I know, more writers are going that route and it doesn't carry the stigma that it used to, but still, it's a two-fold risk: the writing may be wretched, and even if it's okay and you provide a qualified review, the author may not have learned how to handle anything less than whole-hearted adoration with the necessary grace. Rowena reviewed The Other Boyfriend unfavorably three months ago and Sylvia Massara still hasn't gotten over it!

Massara is right on one account: there are best-selling authors who receive bad reviews. She glissandos over the fact that many of these bad reviews come from professional reviewers, though, not just the ones with the grocery list-backgrounds that she disdains, because she's clearly trying to make herself feel better. (There's no accounting for taste, people; that's why some crap books sell.) She also glides right over the fact that as a self-publishing author she's not likely to receive any attention from the professionals.

Sylvia Massara has gotten lots of attention from everyone else this week. This morning I decided not to be one of the bloggers swearing I'd never read any of her books because she'd made such an ass of herself--not that I blame anyone who's put her on their do-not-read lists. I decided to cut her a bit of slack; to separate the writer from the work; to be objective about it all. You know, the way Sylvia Massara wants us to be.

I downloaded the free sample of The Other Boyfriend onto the Kindle.

And I immediately felt as if I were once again in writing workshop, critiquing an early draft to a story. A draft where a person exclaims a full sentence in disbelief while simultaneously taking a deep drag from her cigarette [a group discussion would ensue over whether that's even possible and if it is, should it be left in if it drags a portion of the readers from the story]; where a character who's just requested that her best friend find a boyfriend for a third woman will assume that the subsequent "excited cry" of "Mike" refers to an unexpected mention of a karaoke microphone instead of an eligible male [question: is this supposed to be funny or a hint that the main character's kind of stupid?]. A draft wherein you will find sentences such as this: "It was at times like this that I wished I was a smoker like Monica so I could throw an ashtray at his head, in the hope that it would unscramble his brain and spur him into action so he could free himself of the ball and chain." Said ball and chain is also referred to as the "Singapore Hag," which undoubtedly would lead into a discussion of whether the writer wants her readers to dislike her main character for engaging in such name-calling, and if so, what could she do to make her more interesting, via the writing itself or the character's personality, so that the readers will want to stick with the story. Or, if she's supposed to be a character the reader likes and relates to, a suggestion to take that bit out.

In a writing workshop I'd be okay with reading a manucript of this calibre. I'd be interested to see the next draft, to see what improvements had been made. I'd be happy to be one of the first readers who questions everything in its construction so that once the story's ultimately finished and published no one would ever mentally question or reword how it is told. But I have no interest in reading a published novel of this same quality, even less in blogging about it in a way that puts the author's precious feelings above anything else I might have to say about it.

Book reviews are for readers, not authors. Whining about the ones that don't offer the writer "constructive criticism" when such criticism should have taken place before publication is simply ridiculous.

The only constructive criticism left to offer a writer after the book is published is this: Don't insult your readers. Don't dismiss their opinions as rubbish. Don't accuse them of malice because they didn't like your book.

Negative reviews can often lead other readers to pick up your book, readers who may like it--but not if you've managed to alienate them all through your unprofessional behavior.

(I don't care if you write romances or chicklit: proudly proclaim your pink pride with something other than the font, okay? Do you really want to cause

And then I read the reviewer's post that the author claimed didn't "quantify" why she'd called the plot predictable and the characters one-dimensional as well as all the following comments, including the ones by Anonymous, who seemed so emotionally invested in the book and in putting its detractors in their place that any reasonable person would bet a dollar to a doughnut that Anony had to be the author. By the time I clicked back to the author's blog, looking for additional comments there, she'd deleted them all.

Which of course was her perogative.

And I figured I'd wasted enough time on this particular brouhaha.

But I woke up this morning thinking once again about this:

Oftentimes, the people who set up these kinds of blogs have never written a thing in their lives, except maybe a grocery list. Most are avid readers who think they are qualified to review someone else's work. So it's very sad when they go about damaging the image of upcoming small press and indie authors with the rubbish they write.

and

Please bear in mind that writers work very hard at their craft and the last thing they need is a smartass who makes subjective comments because they don't know how to do anything else.

(Do you see what I mean about the pink font?)

I blog because I'm an avid reader, not because I've published poetry, fiction, journalism. Frankly, I think being an avid reader pretty much takes care of all the qualifications necessary for having a book blog, where basically we all share our thoughts and opinions on what we've read. There are bloggers who gush or snark or journal their way through a book instead of writing the traditional review and they seem to do very well for themselves. There are others who aspire to the Platonic Ideal of reviewing by carefully following the dictates set forth periodically by spokesmembers of the book industry. They market and brand and promote and network and they do very well for themselves, too. There's no right way or wrong way to write about books on a book blog; different approaches will lead to different audiences, that's all.

I don't know this for a fact, but I would assume it's the bloggers who don't have a writing background of some sort that are the most amenable to accepting an ARC from a self-publishing author. I know, I know, more writers are going that route and it doesn't carry the stigma that it used to, but still, it's a two-fold risk: the writing may be wretched, and even if it's okay and you provide a qualified review, the author may not have learned how to handle anything less than whole-hearted adoration with the necessary grace. Rowena reviewed The Other Boyfriend unfavorably three months ago and Sylvia Massara still hasn't gotten over it!

Massara is right on one account: there are best-selling authors who receive bad reviews. She glissandos over the fact that many of these bad reviews come from professional reviewers, though, not just the ones with the grocery list-backgrounds that she disdains, because she's clearly trying to make herself feel better. (There's no accounting for taste, people; that's why some crap books sell.) She also glides right over the fact that as a self-publishing author she's not likely to receive any attention from the professionals.

Sylvia Massara has gotten lots of attention from everyone else this week. This morning I decided not to be one of the bloggers swearing I'd never read any of her books because she'd made such an ass of herself--not that I blame anyone who's put her on their do-not-read lists. I decided to cut her a bit of slack; to separate the writer from the work; to be objective about it all. You know, the way Sylvia Massara wants us to be.

I downloaded the free sample of The Other Boyfriend onto the Kindle.

And I immediately felt as if I were once again in writing workshop, critiquing an early draft to a story. A draft where a person exclaims a full sentence in disbelief while simultaneously taking a deep drag from her cigarette [a group discussion would ensue over whether that's even possible and if it is, should it be left in if it drags a portion of the readers from the story]; where a character who's just requested that her best friend find a boyfriend for a third woman will assume that the subsequent "excited cry" of "Mike" refers to an unexpected mention of a karaoke microphone instead of an eligible male [question: is this supposed to be funny or a hint that the main character's kind of stupid?]. A draft wherein you will find sentences such as this: "It was at times like this that I wished I was a smoker like Monica so I could throw an ashtray at his head, in the hope that it would unscramble his brain and spur him into action so he could free himself of the ball and chain." Said ball and chain is also referred to as the "Singapore Hag," which undoubtedly would lead into a discussion of whether the writer wants her readers to dislike her main character for engaging in such name-calling, and if so, what could she do to make her more interesting, via the writing itself or the character's personality, so that the readers will want to stick with the story. Or, if she's supposed to be a character the reader likes and relates to, a suggestion to take that bit out.

In a writing workshop I'd be okay with reading a manucript of this calibre. I'd be interested to see the next draft, to see what improvements had been made. I'd be happy to be one of the first readers who questions everything in its construction so that once the story's ultimately finished and published no one would ever mentally question or reword how it is told. But I have no interest in reading a published novel of this same quality, even less in blogging about it in a way that puts the author's precious feelings above anything else I might have to say about it.

Book reviews are for readers, not authors. Whining about the ones that don't offer the writer "constructive criticism" when such criticism should have taken place before publication is simply ridiculous.

The only constructive criticism left to offer a writer after the book is published is this: Don't insult your readers. Don't dismiss their opinions as rubbish. Don't accuse them of malice because they didn't like your book.

Negative reviews can often lead other readers to pick up your book, readers who may like it--but not if you've managed to alienate them all through your unprofessional behavior.

Monday, February 07, 2011

George Gissing and Demos: A Story of English Socialism

[Overwhelming proof that I'm the worst of bloggers: I read this particular Gissing last summer, intended the post for BBAW in September, as a thank you to Frisbee for leading me to this book, then abandoned the post, half-finished, when we had computer difficulties for a short period of time. Geez.]

In the end, it becomes fairly clear why [George] Gissing's books have always appealed to a few rather than to many. He was a lonely, conservative atheist, a sensitive and loving observer of nature, devoted to the classics, and gifted as few writers have been in portraying lower-class and middle-class life, thought, and character. Readers who respond to him are likely to be outsiders, "born in exile" too. --Judy Stove, New Criterion, Feb 2004

After completing In the Year of Jubilee back in the spring, I'd been torn as to which George Gissing I wanted to read next. I was leaning toward Born in Exile when Frisbee's post in May led me to pick up Demos instead.

If I tell you that Demos has been regarded as a prototype of Animal Farm, you won't pull a been there, done that on me, will you? (Granted, Animal Farm can be read in a mere 53 minutes or less and Demos will take several days, at the very least, but there's a slow reading movement afoot these days as well as plenty of e-readers for effortless/free downloading of the previously elusive if you don't want to spring for the gorgeous new edition being brought back into print next month by Victorian Secrets ).

Ahem.

So, anyway, George Orwell admired Gissing's work, saying he was "exceptional among English writers" due to his interest "in individual human beings, and the fact that he can deal sympathetically with several different sets of motives" and make "a credible story out of the collision between them."

Despite his admiration, Orwell found it difficult to lay his hands on very many of Gissing's novels since they'd already gone out of print (Orwell was born the year Gissing died, 1903), but he did mention reading a "soupstained" library copy of Demos in his 1948 essay on the novelist.

On Gissing himself, Orwell said:

Gissing was a bookish, perhaps over-civilised man, in love with classical antiquity, who found himself trapped in a cold, smoky, Protestant country where it was impossible to be comfortable without a thick padding of money between yourself and the outer world. Behind his rage and querulousness there lay a perception that the horrors of life in late-Victorian England were largely unnecessary. The grime, the stupidity, the ugliness, the sex-starvation, the furtive debauchery, the vulgarity, the bad manners, the censoriousness — these things were unnecessary, since the puritanism of which they were a relic no longer upheld the structure of society. People who might, without becoming less efficient, have been reasonably happy chose instead to be miserable, inventing senseless taboos with which to terrify themselves. Money was a nuisance not merely because without it you starved; what was more important was that unless you had quite a lot of it — £300 a year, say — society would not allow you to live gracefully or even peacefully. Women were a nuisance because even more than men they were the believers in taboos, still enslaved to respectability even when they had offended against it. Money and women were therefore the two instruments through which society avenged itself on the courageous and the intelligent. Gissing would have liked a little more money for himself and some others, but he was not much interested in what we should now call social justice. He did not admire the working class as such, and he did not believe in democracy. He wanted to speak not for the multitude, but for the exceptional man, the sensitive man, isolated among barbarians.

And in Demos Gissing takes a man who does want to speak for the working class, a man who's a proponent of socialism, of bringing the classes together, and proceeds to bring him to his ruin.

Rather unfairly, from my perspective.

The opening situation is this: a Midlands capitalist with an iron mine and factory blighting otherwise beautiful countryside burns his will and dies before he can write its replacement. His presumed heir, a young local aristocrat, has been sowing his wild oats in Paris and ignoring his mother's pleas to get himself home before it's too late to regain the family estate lost in a previous generation. It's very easy for the reader not to feel too sorry for the aristocrat when he manages to roll in, feverish and delirious from the gunshot wound he's sporting in his side, on the far side of the capitalist's funeral. You had your chance, bucko, and you botched it.

No, the reader's sympathies are with working-class Richard Mutimer of London, who never knew his great uncle, in fact was surprised to learn he hadn't died already years back, who now unexpectedly finds himself his principal heir. Richard has just recently lost his job as a mechanic due to his outspoken radical beliefs. Now he decides to operate his uncle's factory according to these same socialistic principles. He worries how best to prepare his younger brother and sister for the wealth they'll come into when they reach 21. He moves his mother and siblings into a larger house in London and provides financially for his girlfriend and her invalid sister, promising to marry Emma and move her into the manor house in the country once its current tenants have moved out and relocated.

Granted, Gissing has mocked Richard's efforts at self-education and pointed out enough of his shortcomings for the reader to know things won't go smoothly for him as he attempts the rise in class and status. Yet his initial inclinations seem so naturally correct, so well-intended, that it's hard not to expect most difficulties he'll encounter to arise outside himself, rather than from within.

This is the prototype for Animal Farm, however, so money and position corrupt him all too soon and ruin the lives of many. I'll leave the infuriating particularities of his downfall to be discovered by those who'd like to look at the nineteenth century from the perspective of one George Gissing, a man who pitied the poor individually, but didn't care to see the class as a whole promoted; who much preferred the aristocrats as a class, despite their individual failings. It's a bleak philosophy he puts forth in Demos, expanded upon near the end of the novel by a character presumed to be speaking for Gissing, one that reminded me a great deal of a viewpoint encountered in Germinal. (I'll post these sections that I have in mind tomorrow.) It's not a philosophy I endorse, but one I attempt to understand.

Read Demos when you're feeling isolated among the barbarians.

Sunday, February 06, 2011

Reading update, a rather rambling one at that

Reading-wise, I probably have too many irons in the fire right now. I'm three letters into the alphabet in Insectopedia; four chapters into Nixonland; one essay away from the book reviews in The Essential Rebecca West; one act completed in my reread of Othello; random scant stories into Binocular Vision. I've kept Choices in my In Progress widget as penance despite not picking it up since early December (people who tried this after I raved about Mary Lee Settle: oh, this one is not. at. all. like the Settles I've loved). I need to start rereading Atonement for library staff book club. I need to start Safe from the Neighbors just because I want to. I need to stop being afraid of The Waves and float luxuriously upon its waters like W., my poet friend and fellow Woolf reader, instead of remaining stiffly upright (so who's the counterpart to Forster? who's supposed to be Vanessa?), afraid of going out too far.

David imagines himself with octopus arms, but I wish I were an insect with multi-faceted eyes to take in all these books at once.

He Knew He Was Right is now my favorite Trollope. L. and I have had a running joke throughout the years--that the underhanded minister tricked a promise to obey out of me during our wedding ceremony--that I thought about quite often over the week I spent racing through this novel. I don't do obedience. If L. suggests we attempt to stick for a length of time to what he terms an "austerity budget" to achieve some financial goal, I'll concur. If he says DON'T you spend any money you don't have to, I'll come home with a bronze statue of John by-god Wayne or a sleigh bed sticking out of the back of the car and say DON'T you even ask what this cost. And he doesn't. Marriage means recognizing when you'd better back off and think of a better way to word your requests.

But what if there's no give and take, what if the obedience demanded of you also includes swearing that a base falsehood told about you is absolutely true? Would it have been possible for Emily to endure, let alone achieve contentedness in, a marriage to such a paranoid individual as Louis? Our cat Claudius suffers from paranoia* and while we all tolerate and make concessions for the delusions that dictate his behavior, we know his default settings aren't right and no one--human or cat--is willing to fall in line with his way of thinking.

Anyway, I'm rereading Othello, mentioned several times in the Trollope, since I haven't read it since high school and I'm trying to read as organically as I can this year.

Because the dovetailing in the books I've read so far in 2011 has been glorious, although none of it was planned. The Alan Turing and cryptoanalysis of WWII in the Connie Willises reappear in Scarlett Thomas's PopCo; the destruction of the London department stores during the Blitz, first encountered fictionally in Willis, happens in real life in a Rebecca West essay. A saying used to illustrate chaos theory late in the Willis shows up again as the epigraph to Started Early, Took My Dog. Plato's Symposium influences Virginia Woolf's The Waves.

And so it will go, if I'm lucky, through the rest of the year's reading.

~~~

*including the misguided notion that he might be safer disguised as a zebra

David imagines himself with octopus arms, but I wish I were an insect with multi-faceted eyes to take in all these books at once.

He Knew He Was Right is now my favorite Trollope. L. and I have had a running joke throughout the years--that the underhanded minister tricked a promise to obey out of me during our wedding ceremony--that I thought about quite often over the week I spent racing through this novel. I don't do obedience. If L. suggests we attempt to stick for a length of time to what he terms an "austerity budget" to achieve some financial goal, I'll concur. If he says DON'T you spend any money you don't have to, I'll come home with a bronze statue of John by-god Wayne or a sleigh bed sticking out of the back of the car and say DON'T you even ask what this cost. And he doesn't. Marriage means recognizing when you'd better back off and think of a better way to word your requests.

But what if there's no give and take, what if the obedience demanded of you also includes swearing that a base falsehood told about you is absolutely true? Would it have been possible for Emily to endure, let alone achieve contentedness in, a marriage to such a paranoid individual as Louis? Our cat Claudius suffers from paranoia* and while we all tolerate and make concessions for the delusions that dictate his behavior, we know his default settings aren't right and no one--human or cat--is willing to fall in line with his way of thinking.

Anyway, I'm rereading Othello, mentioned several times in the Trollope, since I haven't read it since high school and I'm trying to read as organically as I can this year.

Because the dovetailing in the books I've read so far in 2011 has been glorious, although none of it was planned. The Alan Turing and cryptoanalysis of WWII in the Connie Willises reappear in Scarlett Thomas's PopCo; the destruction of the London department stores during the Blitz, first encountered fictionally in Willis, happens in real life in a Rebecca West essay. A saying used to illustrate chaos theory late in the Willis shows up again as the epigraph to Started Early, Took My Dog. Plato's Symposium influences Virginia Woolf's The Waves.

And so it will go, if I'm lucky, through the rest of the year's reading.

~~~

*including the misguided notion that he might be safer disguised as a zebra

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

A bang, not a whimper

Two months into L.'s retirement, and I'm finished with the stockpiling of books. No more book purchases! Or at least, no purcha...

-

(See also Musee des Beaux Arts ) As far as mental anguish goes, the old painters were no fools. They understood how the mind, the freakiest ...

-

Lou wondered where his information would go when he died. Would filaments of learning plant patterns on earth? Would his brain train the sin...