When the Classics Circuit announced its Ancient Greek tour I was sure I'd go with drama--The Oresteia or An Oresteia, I pondered over the course of several days, occasionally wondering if perhaps I should sign up for a comedy--say, The Frogs--instead of always heading straight for a wallow in the grim and gruesome depictions of extreme family dysfunction.

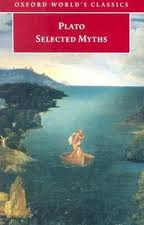

Before I'd committed one way or the other, Plato's Selected Myths, with its lovely Joachim Patenir cover of Charon Crossing the River Styx caught my eye on one of the "just checked in" book carts at the library, and I realized my choice had been made for me.

Plato wrote myths? Did everyone know this but me? I'd been operating for years under the conviction that by the time Socrates and Plato came around, Greek mythology was, if not over for the society at large, at least brushed aside by these emerging powerhouse philosophers, who had more important matters on their minds than relating the further adventures of Zeus and Poseidon and the gang. "The Cave" was an allegory, not a myth, right? Plato was all Politics and Socratic Dialogues and the Academy, um, right?

Well, when I'm wrong (more often than I like to admit), I'm wrong. Plato's philosophical writings incorporate many myths, I now know, both traditional retellings and his own creations.

As Catalin Partenie's introduction tells the reader, "Both Plato's myths and his dialogues are narrative: in all of them a story is being told by a story-teller. But the mythical story is different from the frame-story of the dialogues, in which two or more characters--in a particular setting and at a particular time--carry on a philosophical conversation. The mythical story is a fantastical story, for it always contains a fair amount of fantastical details. Plato is aware of that and he often makes the myth-teller admit it. In Phaedo, for instance, he makes Socrates say, after expounding the long myth about the afterlife, that 'to insist that those things are just as I've related them woud not be fitting for a man of intelligence' . . . The myth, then, is not just fictional (made up), but fantastical (unrealistic), whereas the frame-story of the dialogues contains no fantastical details. This story is certainly fictional, for Plato has invented most of it, but it is a realistic fiction: apart for some incidental anachronisms, all dialogues describe realistic conversations between realistic characters in realistic settings. Thus Plato embeds philosophy-cum-fantastical stories into realistic stories."

Selected Myths pulls ten fantastical stories from eight dialogues of Plato, preceding each with a couple pages of explanatory context. We learn that Plato's setting for a discussion of the philosophical truths regarding love was a symposium, or drinking party, and that a discussion on virtue was set in the house of a rich Athenian where the intellectuals had come to talk. The story of the ancient city of Atlantis is told at a banquet where conversation is to be the "key entertainment."

My favorite myth, "Er's Journey into the Other World," comes from the end of The Republic. Er is killed in battle, but his body doesn't decay like everyone else's. Nevertheless he's placed on a funeral pyre twelve days later where he comes back to life and tells the story of what awaits us all: punishments or rewards both ten times the amount of the earthly deed, experienced for a thousand years in either Hades or Heaven; the Fates, the Spindle of Necessity, the harmony of the spheres, and the lottery that determines an individual's next life, the Plain of Oblivion and the River of Neglect. We're told of Orpheus choosing the life of a swan, Ajax, the incarnation of a lion; Agamemnon, that of an eagle.

"As the luck of the lottery had it, Odysseus' soul was the very last to come forward and choose. The memory of all the hardship he had previously endured had caused his ambition to subside, so he walked around for a long time, looking for a life as a non-political private citizen. At last he found one lying somewhere, disregarded by everyone else. When he saw it, he happily took it, saying that he'd have done exactly the same even if he'd been the first to choose. "

Er tells his funeral party that most souls met with a reversal of fortune during the lottery, but that it is best of us to "always keep to the upward path, and we should use every means at our disposal to act morally and with intelligence, so that we may gain our own and the gods' approval, not only during our stay here on earth, but also when we collect the prizes our morality has earned us. . ."

The quirkiest myth included in Selected Myths would have to be Plato's "The Androgyne," which relates an aetiological story on love. "You see, our nature wasn't originally the same as it is now: it has changed. First, there used to be three human genders, not just two--male and female--as there are nowadays. There was also a third, which was a combination of both the other two. Its name has survived, but the gender itself has died out. In those days, there was a distinct type of androgynous person, not just the word, though like the word the gender too combined male and female; nowadays, however, only the word remains, and that counts as an insult."

The quirkiest myth included in Selected Myths would have to be Plato's "The Androgyne," which relates an aetiological story on love. "You see, our nature wasn't originally the same as it is now: it has changed. First, there used to be three human genders, not just two--male and female--as there are nowadays. There was also a third, which was a combination of both the other two. Its name has survived, but the gender itself has died out. In those days, there was a distinct type of androgynous person, not just the word, though like the word the gender too combined male and female; nowadays, however, only the word remains, and that counts as an insult."Nowadays we're just half of our complete shape (we were round like our original parent: the sun, the male gender; the earth, the female; the moon, the combined gender) because Zeus cut us in half to weaken us and keep us in our place. Love is our desire to once again be whole. Only those from the androgynous gender are heterosexual, the rest are homosexual.

I think anyone who's a fan of Greek mythology or is a Plato newbie like myself would enjoy Selected Myths. I'll definitely seek out The Republic as my next Plato based on my all-to-brief introduction to it here.

But first I want to read some of that grim and gruesome Greek drama. The Oresteia or An Oresteia? I still can't decide!