Now comes the delicate moment when they have to leave the classroom. They have no desire to talk, nor have I. I turn away and look for something in my briefcase. I know the effect Plato's theories of the body being a hindrance to the soul have had on Christianity, and I deplore it; and I also know that Socrates is part of the eternal misunderstanding of Western civilization, but his death never fails to move me, especially when I'm acting the part myself.

When I turn around, most of them have left. A few red eyes, the boys with those averted heads as if to say "Don't think I'm impressed." A lot of noise in the corridor, too loud laughter. But d'India stayed; she really was crying.

"Stop that immediately," I said. "You obviously haven't understood a word of what I've been saying."

"That's not why I'm crying." She was putting her books into her satchel.

"What's the matter then?" Stupid question number 807.

"Everything."

A divine image in tears. Not an uplifting sight.

"'Everything' covers rather a lot of ground."

"I suppose it does." And then, vehemently, "You don't believe it yourself, about the immortality of the soul."

"No."

"Then why do you tell the story as if you did?"

"The situation in that cell has nothing to do with any ideas I might get into my head."

"But why don't you believe it?"

"Because he tries to prove it four times over. A sure sign of weakness, that is. I don't think he believed it himself, not really. But the point is not immortality."

"What is the point, then?"

"The point is that we are capable of thinking about immortality. That is what sets us apart."

"Without our believing in it, you mean?"

"If you ask me, yes. But I'm not very good at this sort of discussion."

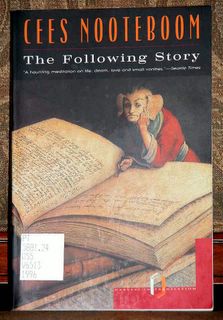

--Cees Nooteboom, The Following Story

Yesterday Dorothy mentioned the Guardian article on the best 25 books of the backlist, and in the article David Mitchell mentioned how he'd stumbled across Nooteboom's novella in Amsterdam and had been enticed to read it by A.S. Byatt's cover blurb. A copy of the book was available in the library, so I managed to find myself mere minutes later engrossed by the story of a former classics instructor now making his living writing "moronic" travel guides, a man who manages to bring up King Lear on page 6 and mention Ovid's The Metamorphoses throughout his tale, evoking Kafka and Jim Crace time and again, although I suppose the Crace I thought of came after the Nooteboom. As Herman Mussert, the narrator, says, "The world is a never-ending cross-reference."

Socrates, as Mussert's former students called him, goes to bed in his apartment in Amsterdam, after an evening spent reading Tacitus and about Java, the subject of his next travel guide, clutching a newspaper clipping of a photograph taken from the spacecraft Voyager. When he awakes, feeling as if he might be dead, he finds himself in Portugal, in the hotel room where he and his married lover stayed 20 years earlier. While Socrates tries to make sense of things he muses as well on time, space, his love of language (he would have insisted upon a translator who understood subjunctive case, for instance), classical writers and the constellations.

A beautiful, ruminative story, one I'll reread most definitely (I was way too jazzed up on coffee to focus well), and really ought to buy so I can mark all my favorite passages.

No comments:

Post a Comment