[Overwhelming proof that I'm the worst of bloggers: I read this particular Gissing last summer, intended the post for BBAW in September, as a thank you to Frisbee for leading me to this book, then abandoned the post, half-finished, when we had computer difficulties for a short period of time. Geez.]

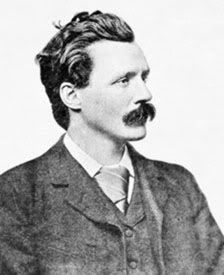

In the end, it becomes fairly clear why [George] Gissing's books have always appealed to a few rather than to many. He was a lonely, conservative atheist, a sensitive and loving observer of nature, devoted to the classics, and gifted as few writers have been in portraying lower-class and middle-class life, thought, and character. Readers who respond to him are likely to be outsiders, "born in exile" too. --Judy Stove, New Criterion, Feb 2004

After completing In the Year of Jubilee back in the spring, I'd been torn as to which George Gissing I wanted to read next. I was leaning toward Born in Exile when Frisbee's post in May led me to pick up Demos instead.

If I tell you that Demos has been regarded as a prototype of Animal Farm, you won't pull a been there, done that on me, will you? (Granted, Animal Farm can be read in a mere 53 minutes or less and Demos will take several days, at the very least, but there's a slow reading movement afoot these days as well as plenty of e-readers for effortless/free downloading of the previously elusive if you don't want to spring for the gorgeous new edition being brought back into print next month by Victorian Secrets ).

Ahem.

So, anyway, George Orwell admired Gissing's work, saying he was "exceptional among English writers" due to his interest "in individual human beings, and the fact that he can deal sympathetically with several different sets of motives" and make "a credible story out of the collision between them."

Despite his admiration, Orwell found it difficult to lay his hands on very many of Gissing's novels since they'd already gone out of print (Orwell was born the year Gissing died, 1903), but he did mention reading a "soupstained" library copy of Demos in his 1948 essay on the novelist.

On Gissing himself, Orwell said:

Gissing was a bookish, perhaps over-civilised man, in love with classical antiquity, who found himself trapped in a cold, smoky, Protestant country where it was impossible to be comfortable without a thick padding of money between yourself and the outer world. Behind his rage and querulousness there lay a perception that the horrors of life in late-Victorian England were largely unnecessary. The grime, the stupidity, the ugliness, the sex-starvation, the furtive debauchery, the vulgarity, the bad manners, the censoriousness — these things were unnecessary, since the puritanism of which they were a relic no longer upheld the structure of society. People who might, without becoming less efficient, have been reasonably happy chose instead to be miserable, inventing senseless taboos with which to terrify themselves. Money was a nuisance not merely because without it you starved; what was more important was that unless you had quite a lot of it — £300 a year, say — society would not allow you to live gracefully or even peacefully. Women were a nuisance because even more than men they were the believers in taboos, still enslaved to respectability even when they had offended against it. Money and women were therefore the two instruments through which society avenged itself on the courageous and the intelligent. Gissing would have liked a little more money for himself and some others, but he was not much interested in what we should now call social justice. He did not admire the working class as such, and he did not believe in democracy. He wanted to speak not for the multitude, but for the exceptional man, the sensitive man, isolated among barbarians.

And in Demos Gissing takes a man who does want to speak for the working class, a man who's a proponent of socialism, of bringing the classes together, and proceeds to bring him to his ruin.

Rather unfairly, from my perspective.

The opening situation is this: a Midlands capitalist with an iron mine and factory blighting otherwise beautiful countryside burns his will and dies before he can write its replacement. His presumed heir, a young local aristocrat, has been sowing his wild oats in Paris and ignoring his mother's pleas to get himself home before it's too late to regain the family estate lost in a previous generation. It's very easy for the reader not to feel too sorry for the aristocrat when he manages to roll in, feverish and delirious from the gunshot wound he's sporting in his side, on the far side of the capitalist's funeral. You had your chance, bucko, and you botched it.

No, the reader's sympathies are with working-class Richard Mutimer of London, who never knew his great uncle, in fact was surprised to learn he hadn't died already years back, who now unexpectedly finds himself his principal heir. Richard has just recently lost his job as a mechanic due to his outspoken radical beliefs. Now he decides to operate his uncle's factory according to these same socialistic principles. He worries how best to prepare his younger brother and sister for the wealth they'll come into when they reach 21. He moves his mother and siblings into a larger house in London and provides financially for his girlfriend and her invalid sister, promising to marry Emma and move her into the manor house in the country once its current tenants have moved out and relocated.

Granted, Gissing has mocked Richard's efforts at self-education and pointed out enough of his shortcomings for the reader to know things won't go smoothly for him as he attempts the rise in class and status. Yet his initial inclinations seem so naturally correct, so well-intended, that it's hard not to expect most difficulties he'll encounter to arise outside himself, rather than from within.

This is the prototype for Animal Farm, however, so money and position corrupt him all too soon and ruin the lives of many. I'll leave the infuriating particularities of his downfall to be discovered by those who'd like to look at the nineteenth century from the perspective of one George Gissing, a man who pitied the poor individually, but didn't care to see the class as a whole promoted; who much preferred the aristocrats as a class, despite their individual failings. It's a bleak philosophy he puts forth in Demos, expanded upon near the end of the novel by a character presumed to be speaking for Gissing, one that reminded me a great deal of a viewpoint encountered in Germinal. (I'll post these sections that I have in mind tomorrow.) It's not a philosophy I endorse, but one I attempt to understand.

Read Demos when you're feeling isolated among the barbarians.

No comments:

Post a Comment